For anyone interested in Western art, it pays to go South. For those already living in the Southeast, the motto of the Booth Museum applies: “Explore the West without leaving the South.” Since 2003 the Booth, in quaint Cartersville, Ga., has showcased Western-themed paintings, sculpture, photography and artifacts in what is now (after a 2009 expansion) a 120,000-square-foot limestone building designed to resemble a modern pueblo. Some 40 miles northwest of Atlanta, the museum is a proud affiliate to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Location notwithstanding, it is the world’s largest permanent exhibition space for Western art.

The Booth’s American West Gallery, divided into interpretive themes, covers everything from the classic works of George Catlin, Charles M. Russell, Frederic Remington and Charles Schreyvogel to notable creations by such recent masters as Howard Terpning, Frank McCarthy, G. Harvey and Andy Warhol. The Frank Harding Cowboy Gallery features 30-plus paintings and sculptures of cowboys and cowgirls at work and play. More than 150 American Indian artifacts from tribes spanning the nation draw visitors to the Native Hands Gallery. An original 1865 stagecoach graces the Neva & Don Rountree Heading West Gallery, alongside depictions of fur trappers and mountain men. Other galleries showcasing the permanent collection include the Modern West Gallery (a sampling of artwork from the past half century), the Lucinda & James Eaton Sculpture Atrium (traditional and contemporary figures) and, on the lower level, the Sagebrush Ranch (an interactive gallery organized like a working ranch and designed for children, who can saddle up and play Western dress-up). Amid the Western-themed galleries are a War Is Hell gallery, featuring Civil War art, and the Carolyn and James Millar Presidential Gallery, with a portrait and original signed letter from every U.S. president from George Washington to Donald Trump.

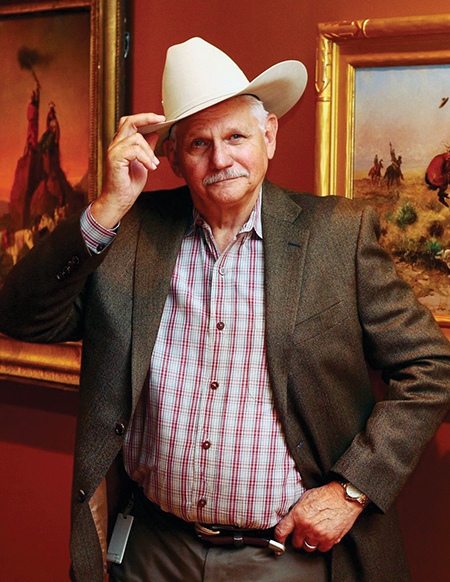

The museum’s namesake is Atlanta businessman Sam Booth, who was a friend and mentor to the family of Western art collectors who founded the Booth and have chosen to remain anonymous. The Booth’s director of special projects, Jim Dunham, doubles as president of the Wild West History Association and once upon a time in the West taught gun tricks and fast draw techniques to Hollywood actors. A long-ago art major at the University of Colorado (1961–66), Dunham counts three paintings among his favorites at the Booth—Diamond A Cowboy, by James Reynolds, Village of Pilar, N.M., by Walt Gonske and Indian With Aura, by Fritz Scholder.

“The Western art here is all about the narrative and is also highly diverse, with many female artists, black artists, American Indian artists and Asian artists,” says Durham. “What makes the museum unique is the vast amount of art by living, working artists. The collection includes styles from photo realism to abstract. The collectors—like myself—were influenced by Western movies and television, especially the so-called adult TV ‘oaters’ of the 1950s and ’60s.”

Any visitor who grew up on Hollywood Westerns will delight in the collection of movie posters, dime novels and action-packed magazine covers that recall such legendary screen figures as Tom Mix, Ken Maynard, Gene Autry and John Wayne. The mythical frontier presented at the Booth also appeals to boys and girls who didn’t grow up playing cowboys and Indians by day and watching prime-time Westerns by night.

Dunham enjoys giving lectures at the Booth. “I started a series titled ‘They Were From Georgia.’ These are based on historical people born in Georgia who became famous out West. The talks include Doc Holliday, Heck Thomas, Pink Higgins, John Bozeman, John Charles Frémont and, of course, Soapy Smith.”

So it happens the South’s connection with the West is historic as well as artistic—and the Booth is the place those connections come to life. WW