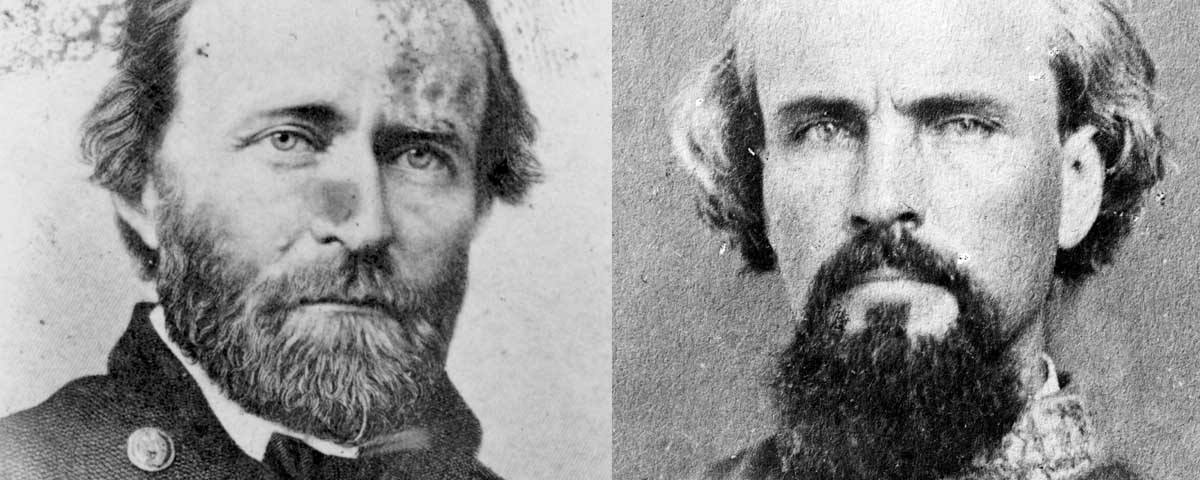

Born to Battle: Grant and Forrest: Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga by Jack Hurst Basic Books, 2012, $32

Born to Battle: Grant and Forrest: Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga by Jack Hurst Basic Books, 2012, $32

In his new book on the Western Theater in the years 1862-63, Jack Hurst finds intriguing, overlooked similarities in battlefield opponents Ulysses S. Grant and Nathan Bedford Forrest. Both men suffered poverty, hardship and social ostracism before the war—experiences Hurst maintains were the source of their strength on the battlefield. Neither was a member of the military or social elite that Hurst contends dominated the high command of their respective armies. In the less class-conscious North, Grant could overcome this liability. But Hurst argues that the Confederacy’s “insistence on blue-blood leadership” caused the Southern high command to spurn Forrest, thereby depriving the South of the full talent of the one man who stood a chance of stopping Grant. “Southern insularity,” Hurst writes, “predestined the Confederacy to squander the brilliance of Forrest, whose fertile brain and vicious valor might have helped fashion an opposite outcome” to the Civil War.

Forrest’s final alienation from the Confederate command hierarchy came when the Army of Tennessee’s commanding general Braxton Bragg failed to pursue the routed Union army after the Battle of Chickamauga. That decision ended any chance, however slim, Forrest may have had to help shape Southern strategy in that crucial year. (Neither Forrest’s most controversial battle, Fort Pillow, nor his greatest victory, Brice’s Cross Roads, are included in Born to Battle because they occurred in 1864.)

Hurst reaffirms the central role Grant played in shaping the outcome of the war in the West. He offers a lively, straightforward account of Grant’s actions at Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga. His bold assertion that squandering Forrest’s potential was a principal cause of Confederate defeat is certain to stir controversy.

—Peter Cozzens

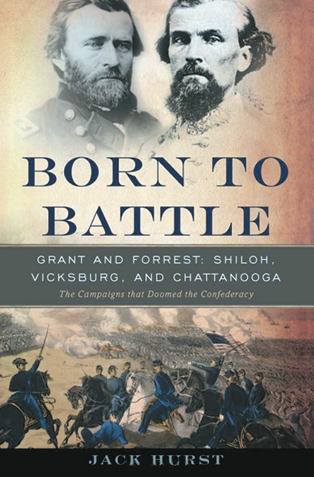

The Confederate Heartland: Military and Civilian Morale in the Western Confederacy by Bradley R. Clampitt Louisiana State University Press, 2011, $39.95

The Confederate Heartland: Military and Civilian Morale in the Western Confederacy by Bradley R. Clampitt Louisiana State University Press, 2011, $39.95

The title of Bradley Clampitt’s new book is a bit misleading. He does not cover the entire war but focuses only on the last 16 months of the conflict in the Western Theater, an area of consistent Union success and Confederate failure. But if an author is to be judged by advancing a convincing argument, Clampitt has achieved a notable success. He aims to provide “a corrective to the notions that Confederate morale steadily declined after 1863 and…had reached a critical low after the re-election of Abraham Lincoln in 1864.” He is being too modest. His corrective establishes a new baseline to our understanding of Confederate morale in its heartland.

At the onset, Clampitt reminds us of two essential but often overlooked principles that inform his book. First, and bedrock: Confederate defeat was not inevitable. Events in the war’s final year were not writ in stone. Second, and closely related, modern readers know how the war ended, so Appomattox colors everything they read about it. What Clampitt demonstrates is that Rebel morale in the West was sometimes altogether independent of the fortunes of troops in the East.

Clampitt shows that Heartland Confederates more or less assumed Robert E. Lee would successfully defend Richmond. They focused mostly on the Army of Tennessee, and despite the loss of Atlanta and the bloody battles in and around the city, their morale didn’t plummet until after the fateful Tennessee battles of Franklin and Nashville in late 1864. Until then, both civilians and soldiers remained convinced the Confederacy could actually win the war, which explains why they persisted even after Atlanta fell in September, even after Sherman marched to the sea and John Bell Hood struck out on his ultimately catastrophic campaign into Tennessee.

Not that Confederate morale in the West didn’t undergo ebbs and flows in 1864. Clampitt documents several high and low points. Among the former: the appointment of Joseph E. Johnston to command the Army of Tennessee in January 1864 and his victory at Kennesaw Mountain during the Atlanta Campaign. Johnston’s retreat from Cassville, his replacement by Hood and the fall of Atlanta dealt only transitory blows to Confederate morale.

Without judging who was the superior general, Clampitt sheds considerable light on the ancient debate about Johnston and Hood. The soldiers’ preference, echoed by civilians, was starkly clear. They trusted and loved Johnston, and most were wary of Hood. In addition to the impact of military campaigns on Confederate morale, Clampitt discusses the influence of Lincoln’s re-election, peace negotiations and the proposal to arm blacks to fight for the Confederacy. But none of these events, either singly or together, affected Confederate morale as much as the stunning defeats at Franklin and Nashville. After that, even among the many still-defiant Rebels, none believed victory for the South was possible. This was the true breaking point for Confederate morale.

—Thomas E. Schott

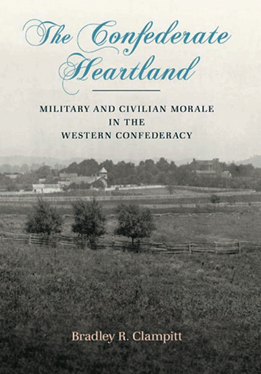

Decided on the Battlefield: Grant, Sherman, Lincoln and the Election of 1864 by David Alan Johnson Prometheus Books, 2012, $27

Decided on the Battlefield: Grant, Sherman, Lincoln and the Election of 1864 by David Alan Johnson Prometheus Books, 2012, $27

In Decided on the Battlefield, author David Alan Johnson makes the case that the United States likely would have ceased to exist in practical terms had Lincoln lost the 1864 election to his Democratic counterpart, General George B. McClellan. Johnson highlights a North America that might well have split into several different countries, including a yet again independent Texas Republic; a collection of smaller states that, for instance, might not have later rescued European allies in two world wars.

While Johnson’s counterhistory is certainly far-fetched, the idea of the 1864 election as a turning point is hardly new. One of the hidden surprises in the book is Johnson’s account of the 1864 Democratic and Republican national conventions. For readers somewhat familiar with how 20th- and 21st-century conventions work, there will be delightful surprises about how these democratic and raucous events functioned in the mid-19th century, without television, microphones or even lights. It is clear that some aspects of politics were still “politics,” though in other ways America was still raw and unfinished.

While far from groundbreaking, it is a book that will certainly stimulate students of “what if,” and perhaps remind once again to what extent great turning points in the war often began in the anxious mind of a worried president haunting the War Department telegraph office.

— Jack Trammell

America’s Great Debate: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise That Preserved the Union by Fergus M. Bordewich Simon & Schuster, 2012, $30

America’s Great Debate: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise That Preserved the Union by Fergus M. Bordewich Simon & Schuster, 2012, $30

Fergus Bordewich’s epic account of the famed Compromise of 1850 is a notably readable narrative of the last effort to prevent sectional war in the United States and the horrors that occurred thereafter. Bordewich, a master storyteller, keeps the events alive with verve and skill.

Focusing on the nation’s westward expansion, slavery and the Compromise of 1850 itself, Bordewich explores the dramatic congressional debate of 1849-50 and the future course of the Union. At issue was the thorny problem of whether the states of Texas and California would be admitted as slaveholding or free. Grappling for a solution were great elder statesmen—Daniel Webster, John Calhoun and Henry Clay—who anguished over compromise that would allow for California’s admission to the Union as a free state and somehow put an end to the nation’s conflict over slavery. When Clay tried unsuccessfully to lead a compromise, a cast of new characters—William Seward, Jefferson Davis and Stephen A. Douglas—emerged who would shape the nation’s politics while slavery continued to divide the republic. In the short term, Douglas managed to push through a compromise that saved the United States from collapse, but at a cost. Strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act, which bolstered the legal claim of slaveholders upon slaves who fled North, was part of the compromise. It only exacerbated the friction between North and South, however, causing many Northern states to adopt “Liberty” laws to protect runaway slaves in contravention of the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Act.

Bordewich brings complicated political characters to life: Webster, who even as an ardent Yankee strongly supported the strengthened Fugitive Slave Act; Calhoun, who believed emphatically in the superiority of the white race; and Douglas, the so-called “Little Giant, whose two marriages were to daughters of prominent Southern families.

For those interested in alternative dispute resolution, namely mediation, the 1850 crisis offers many lessons on how peace, even though temporary, may be achieved among strident adversaries. With the resolution, as with any, are also unintended consequences. The lessons are relevant for today. Even with strident political discourse there is a need for civility and cooperation in the government.

—Frank J. Williams

The Civil War in the West: Victory and Defeat From the Appalachians to the Mississippi by Earl J. Hess University of North Carolina Press, 2012, $40

The Civil War in the West: Victory and Defeat From the Appalachians to the Mississippi by Earl J. Hess University of North Carolina Press, 2012, $40

The outcome of the Civil War was decided, according to Earl J. Hess, largely because of “what each side did, or failed to do, in the West.” In this latest contribution to the Littlefield History of the Civil War Era series, Hess presents a distinctly unconventional examination of how the war unfolded between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. But rather than give a detailed recapitulation of the major engagements in the West, he focuses instead on subjects usually ignored in operational surveys, such as logistics, transportation, military/civilian relations, contrabands and the problem of supplying food for the armies’ men and animals.

“Geography, more than any other factor, made the Civil War in the West unique,” Hess writes. He carefully analyzes how Union commanders astutely used the region’s network of railroads and rivers to invade and occupy Confederate territory and also triumph on the battlefield. Mobility, he stresses, was vital to the Union’s success.

Confederate defeat, however, cannot be attributed solely to insufficient resources, Hess writes. He convincingly shows that the Rebels “made poor use of what resources were available to them because of poor management, poor decision making at high levels, and the bad luck of having generals who could not learn how to effectively command.”

Hess is a master chronicler of this region, having spent much of his professional career immersed in Western archives and tramping Western battlefields. His prose is strong and confident, mirroring the character of the men about whom he writes so eloquently.

—Gordon Berg

Enduring Legacy: Rhetoric and Ritual of the Lost Cause by W. Stuart Towns University of Alabama Press, 2012, $37.50

Enduring Legacy: Rhetoric and Ritual of the Lost Cause by W. Stuart Towns University of Alabama Press, 2012, $37.50

The Lost Cause, like William Faulkner’s past, is not dead—and, according to W. Stuart Towns, it’s not even past. In this deftly reasoned and cogently argued exploration of the rhetoric and ritual associated with the South’s most enduring myth, Towns stresses that 20th-century white Southerners learned most of what they feel about race, the North, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and themselves from Lost Cause rhetoric.

A communications professor, Towns examines the public oratory that formed the bedrock of Southern ideology after the war ended. Speeches at Confederate Memorial Day ceremonies, regimental reunions and monument dedications extolled the valued heritage of a white society destroyed by the war. For the formerly ascendant class, Lost Cause ritual and oratory “created a sense of order and community out of the chaos, uncertainty, and despair of defeat.”

Towns argues convincingly that Lost Cause orators spread their social vision so effectively and persuasively “that they are still alive today and will remain so well into the future.” In the desegregation and civil rights decades of the 1950s and 1960s, he notes, Lost Cause rhetoric “justified, vindicated, defended, and explained states’ rights and white supremacy as enduring and fundamental planks of the ‘southern way of life.’ ” Towns finds a clear link between the “right of secession” and “sacred honor” rationales offered by Confederates icons John Bell Hood and John Brown Gordon in the 1870s and the code words “states’ rights” and “constitutional liberty” that Governors Ross Barnett and George Wallace used in the 1960s.

Towns hopes the current sesquicentennial commemoration will be used North and South to more fully understand the rhetoric underlying what Robert Penn Warren called “the great single event of our history.”

—Gordon Berg