Americans who loved Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt did so not only because the First Couple saw their country through depression and war but because they empathized with regular people. Alas, the Roosevelts had no empathy for one other.

Kathryn Smith and Susan Quinn show that the Roosevelts stayed together after Eleanor’s 1918 discovery of her husband’s affair out of her sense of duty and his determination to rise in politics, then impossible for a divorcé.

Marital love yielded to long-term relationships with other parties who sacrificed themselves—one losing a career, the other her life—serving the two principals.

Eleanor nurtured Franklin’s ambitions after his disastrous 1920 bid for the vice presidency and his bout with polio. While he was boozily sorting out his life aboard a houseboat off Florida, she was developing as a force in New York Democratic politics by barnstorming New York on behalf of Al Smith’s 1924 gubernatorial bid.

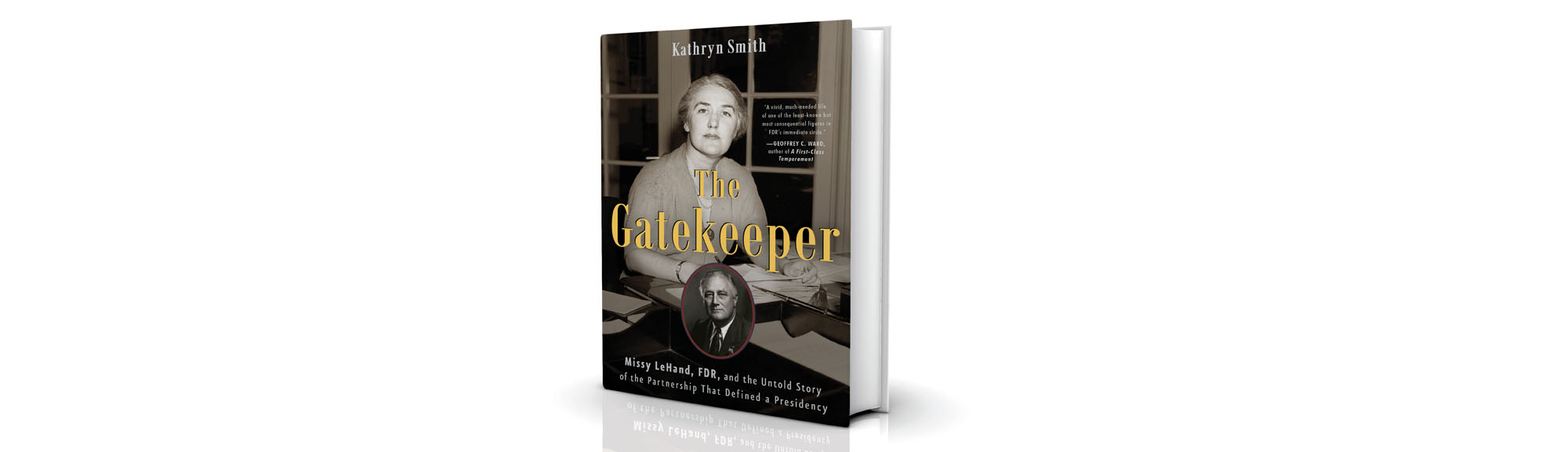

Aboard the Larooco, Franklin caroused with advisor Louis Howe and a “young woman of undistinguished background and shrewd judgment.” Marguerite “Missy” LeHand had joined Franklin’s staff as his private secretary in 1920. In her deeply researched volume, Smith explains that even before FDR’s polio crisis, Missy was his closest companion. Franklin could not stand to be alone, so LeHand became a sidekick, accompanying him on the raucous houseboat, at Warms Springs, and in the White House, where she functioned as Roosevelt’s de facto chief of staff.

In The Gatekeeper, Smith forthrightly addresses the question of whether LeHand and FDR were lovers. Smith quotes son James Roosevelt as writing: “I suppose you could say they came to love one another, but it was not a physical love.”

Smith tells in poignant detail the often rollicking but ultimately sad story of a woman who served her president, as he said, “so well for so long and asked so little in return.”

Missy did love “the Boss,” but the workload, the drinking, the smoking, and FDR’s neediness destroyed her health. LeHand never recovered from a 1941 heart attack and stroke, dying in July 1944 at 47.

While Franklin and Missy were in cahoots, Eleanor was stretching her political legs and private life. In Eleanor and Hick, Quinn recounts the 1932 campaign meeting between the candidate’s wife and Lorena Hickok, a heavy, hard-drinking, chain-smoking Associated Press reporter whose writing gained her Eleanor’s trust. Before long, “Hick” was in love with the new first lady, who, as Quinn writes, “seemed to feel just as passionately about Hick.”

Hick’s life was journalism, but increasing closeness to the first lady shredded her objectivity and she had to quit the AP. Eleanor helped engineer a job for her with Harry Hopkins’ New Deal relief programs. Hick traveled widely, reporting to Hopkins and copying in ER. Hopkins used Hickok’s material to direct relief funds.

Hick fantasized about having Eleanor all to herself, but Quinn mines their correspondence to show Hick’s dawning recognition that Eleanor belonged not only to her, but to her family and her country. They made an accommodation: Hick moved into the White House, continuing to do legwork for Hopkins and pining for the moments she had with Eleanor. Quinn quotes from their letters, making a case for a relationship both deep and passionate.

Still, the two could never be together and eventually Hick, while still living at the White House, took another lover.

Hick’s letters demonstrate that even after their relationship ended, she pushed Eleanor to become involved in human rights, the cause that brought Mrs. Roosevelt postwar acclaim.—Nancy Tappan