Hood’s Texas Brigade in the Civil War Edward B. Williams McFarland & Co. 2012, $45

Hood’s Texas Brigade in the Civil War Edward B. Williams McFarland & Co. 2012, $45

The last men in the ragged gray line to emerge from the chilly morning mists and stack arms one final time were from Texas. They were all that was left of the once-proud Army of Northern Virginia’s Texas Brigade, men Robert E. Lee said he had come to rely on “in all tight places.” Made up of the 1st, 4th and 5th Texas Infantry and augmented first by the 18th Georgia and later by the 3rd Arkansas, they fought in every major engagement in the East, from the Virginia Peninsula to Petersburg, missing only Chancellorsville. They also went west with James Longstreet’s Corps and fought at Chickamauga and Knoxville. Now only 617 were left to surrender on April 12, 1865.

Edward B. Williams, an independent military historian, has chronicled the exploits of this valiant fighting unit from its formation to its surrender and beyond in almost mind-numbing detail. Indeed, information about the brigade abounds, primarily manuscripts, diaries, personal papers and letters collected at Hill College’s Confederate Research Center in Hillsboro, Texas, and Williams seems to have read them all.

While the monograph is clearly a labor of love, writing in the active voice and some judicious editing of anecdotes and quotations would have made the narrative flow more harmonious. The book could also have easily done without some of the author’s breathless hyperbole (e.g., “At least they were on their way somewhere even though they all knew that that somewhere might mark the site of their extinction.”)

But for those interested in detailed descriptions of the battles and camp life of this renowned Civil War unit, this book can be a worthy companion to the four volumes Colonel Harold Simpson wrote more than a quarter century ago. By taking a chronological approach, Williams lets the reader reference specific chapters in order to examine events in the brigade’s history.

Though the brigade had eight different commanders, it came to be known by the most colorful, John Bell Hood. He led the unit in its first significant action at Gaines’ Mill on June 27, 1862, suffering 611 casualties. In crediting the 4th Texas with breaking the Union line, General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson concluded, “The men who carried this position were soldiers, indeed.”

But the bloodletting on the Peninsula was only a preview of things to come. By the Wilderness in May 1864, the unit was down to about 800 effectives. Fewer than half emerged from that blood-drenched tangle of underbrush to man the Richmond–Petersburg defense lines until the final days of the war.

The chapter describing the Texans’ homeward trek after the surrender is one of Williams’ best. The Hood’s Texas Brigade Association was formed in 1872 and met “with great fanfare” nearly every year until 1933. Since 1966, the memory of the Texas Brigade has been carried forward by the biennial meetings of the Hood’s Texas Brigade Association, Reorganized.

—Gordon Berg

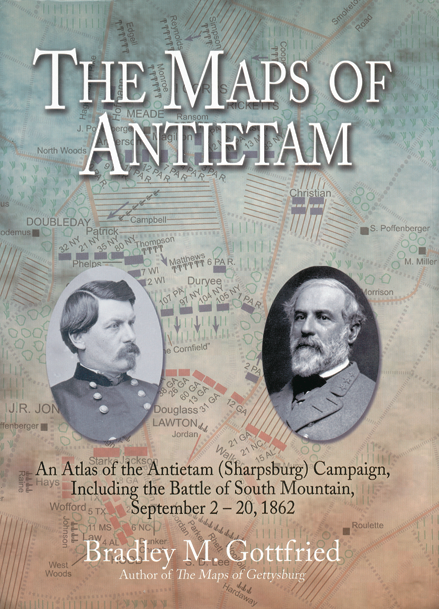

The Maps of Antietam Bradley M. Gottfried Savas Beatie 2012, $39.95

The Maps of Antietam Bradley M. Gottfried Savas Beatie 2012, $39.95

This impressive study of what is more commonly referred to as the Maryland Campaign of 1862 joins similar volumes on Gettysburg, First Bull Run and Chickamauga to comprise the four-volume (so far) Civil War atlas series from Savas Beatie. The format is familiar: a series of facing pages, each with a color map covering a specific time period on the right, and a corresponding narrative page on the left. It’s an effective formula, and again serves Gottfried well in his third such effort.

The maps are grouped into 21 sets or “action-sections” that cover the period from September 2, 1862, through 10:30 a.m. on September 20. Nine maps look at the Army of Northern Virginia’s advance into Maryland through the 13th; 35 more cover events at the South Mountain gaps; another 10 examine the siege and capture of Harpers Ferry; and nine focus on the armies’ movements toward Sharpsburg and the battle preparations through the night of September 16-17. The heart of the book is the series of 53 maps analyzing the fighting outside Sharpsburg on the 17th, from 5:15 a.m. to nightfall. Wrapping things up are seven maps on the often-overlooked Battle of Shepherdstown, along with full orders of battle.

The maps are clean, clear and easy to follow—which is to say, they’re unrealistic. I don’t mean this in a pejorative way, even though true map mavens may decry the general depictions of elevation. We humans need events put into a nice, chronological narrative to make sense of them, but that’s not the way life unfolds. The maps and texts here tell a story, and tell it well. But it’s impotant to keep in mind that it’s a story, not necessarily the story. With this many maps, disagreements on details large and small are inevitable. That aside, this book will definitely help any student adeptly arrange the pieces of the Antietam puzzle.

—Harry J. Smeltzer

The Civil War at Sea by Craig L. Symonds Oxford University Press 2012, $17.95

The Civil War at Sea by Craig L. Symonds Oxford University Press 2012, $17.95

This slim volume should be the starting point for any novice wishing to learn the fundamentals of Civil War naval operations, and not just those that occurred in salt water (as the book’s title implies). Though composed of six stand-alone essays, The Civil War at Sea presents a concise history of the conflict’s many naval operations. Only campaigns where the navies’ roles proved insignificant (e.g., the Red River Campaign) go unmentioned.

Symonds opens with a look at the dramatic technological revolution in vessels and weaponry that occurred in the 1850s. He follows with a chapter on the blockade and the blockade runners, asserting that the North “almost certainly” could still have won without the Anaconda Plan, but it did save “many thousands of lives.” In “The War on Commerce,” Symonds compares the blockade with the Confederate strategy of guerre de course, which wasn’t as successful but did result in eight commerce raiders destroying 284 Union ships. The essay “ ‘Unvexed to the Sea’: The River War” focuses on how the North triumphed on the Western waters because of solid cooperation between the Army and Navy and the inability of the Confederacy to construct an adequate freshwater naval response. When the cooperation faltered, the South prevailed, as Symonds demonstrates in “Civil War Navies and the Siege of Charleston.” The final essay, appropriately titled “The End Game: Mobile, Wilmington, and the Cruise of the Shenandoah,” recounts the closing of the remaining ports east of the Mississippi River as well as the 58,000-mile excursion of the Confederate raider Shenandoah before it lowered its flag in November 1865.

Symonds also examines the often-overlooked, one-sided rivalry between Admiral David Dixon Porter and his foster brother Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, as well as the doleful consequences to the Confederacy because of its inability to build an engine suitable for propelling an ironclad.

As he did in his award-winning Lincoln and His Admirals, Symonds ably demonstrates his literary and research abilities here. Even knowledgeable readers will benefit from his insightful analysis and the bibliographical essay, which details both classic and recent scholarship.

—Lawrence Lee Hewitt

War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes During the Civil War by Lisa M. Brady University of Georgia Press 2012, $24.95

War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes During the Civil War by Lisa M. Brady University of Georgia Press 2012, $24.95

It was only a matter of time before someone trained in the growing field of environmental history decided to study the interactive relationship between the Union military effort to suppress the Southern rebellion and the environment with which the men in blue had to contend.

That military operations have a tremendous impact on the physical environment, and the physical environment in turn exerts a powerful impact on military operations, is well known to most who have studied the history of warfare. So too is the fact that participants often reflect—in many cases profoundly—upon their experience with the environment and that it can have a powerful impact on them. Notions of “progress” and “improvement” were inextricably linked in the minds of 19th-century Americans—especially in the free states—with the conquest of the natural environment.

In War Upon the Land (described on the book jacket as the “first book-length environmental history of the American Civil War”), Lisa Brady offers an intriguing examination of the interaction between the armies and the natural environment. She opens with an effectively constructed and informative overview of concepts that environmental historians use to frame their analysis, and the forces that shaped how Americans back then thought about the environment. This is followed by chapters on the consequences of three major military campaigns: Vicksburg, the Shenandoah Valley in 1864 and William T. Sherman’s marches through Georgia and the Carolinas—and what shaped the interplay between the soldiers and the environment. Brady closes by identifying how the devastation of the war helped spark the wilderness and battlefield preservation movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Brady delivers well-constructed narratives of events, as well as thoughtful and persuasive analysis. Still, it’s easy to predict that many readers will wish she had been a bit more comprehensive in her treatment of the war. After all, the campaigns that took place in the swamps of the Virginia Peninsula, the Wilderness and the mountains of eastern Tennessee seem at least as worthy of attention from environmental historians as those that took place along the Mississippi River. In the final analysis, though, while much more remains to be said about how the environment shaped the war’s military conduct—and vice versa—Brady has produced an excellent book and made a welcome contribution to the scholarship.

—Ethan S. Rafuse