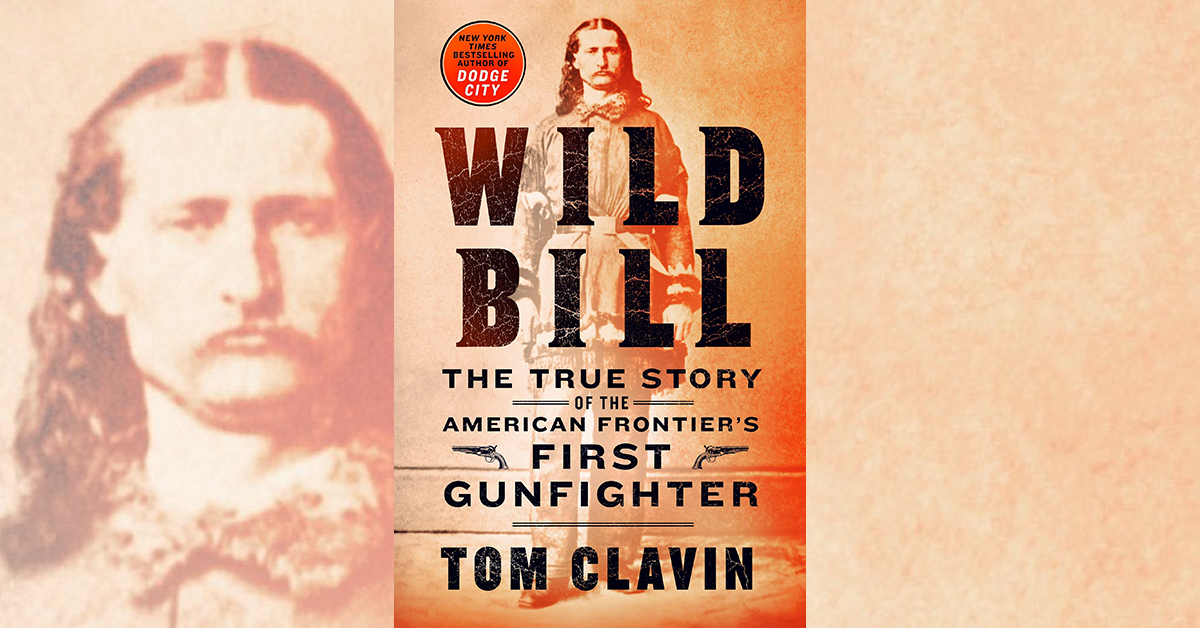

Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter, by Tom Clavin, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2019, $29.99

New York publishers haven’t forgotten the Wild West, at least not the big names in the Wild West, and Will Bill Hickok has a name recognition right up there with his friend Buffalo Bill Cody, sometime lawman Wyatt Earp and outlaw Billy the Kid. The latter three have no doubt been resurrected in books (nonfiction and fiction) and movies more frequently than Hickok, but Wild Bill is catching up. In 2018 Maryland-based TwoDot published Aaron Woodard’s The Revenger: The Life and Times of Wild Bill Hickok (reviewed in the April 2019 issue). Now comes Wild Bill, by Tom Clavin. His 2017 book Dodge City became a national bestseller, so it’s no surprise the author would stick with another tried-and-true Old West name. James Butler Hickok, Clavin suggests, was “arguably the most iconic of all.”

Clavin, like Woodard before him, acknowledges the late researcher-writer Joseph G. Rosa’s contributions to the Hickok story. No honest author can get around crediting Rosa, whose career centered on tracking down everything Wild Bill said or did. Rosa wrote They Called Him Wild Bill (1974), what many consider the definitive biography, though Clavin knocks it down a peg or two for being “a somewhat mind-numbing saga of facts and disclaimers and rebuttals ricocheting off each other.” Rosa followed up with such companion volumes as The West of Wild Bill Hickok (1982) and Wild Bill Hickok, Gunfighter (2001). One might wonder whether there is anything left to write about the scout/spy/lawman/gambler/unsuccessful actor who became a legend in his lifetime and even more famous for drawing a “losing hand” at the hands of an assassin on Aug. 2, 1876, in Deadwood, Dakota Territory. To be honest, there’s not all that much, though sure-handed Clavin does present familiar material in new and entertaining ways and doesn’t get bogged down by minutia, speculation or attempts to sort out conflicting tales.

While the book’s subtitle trumpets Hickok as “the American frontier’s first gunfighter,” that contention is arguable. Eighteen months after a face-to-face victory over Davis Tutt in Springfield, Mo., on July 21, 1865, he unquestionably became a legendary shootist, thanks in large part to a splashy article in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. His first gunfight dates back to 1861, when he shot hard case David McCanles and two others at Rock Creek Station in Nebraska Territory (a judge ruled the controversial killings “self-defense”). But even that firefight came seven years after one Jonathan R. Davis emerged unscathed from a California shootout in which he killed 11 men (seven with a Colt revolver, four with a bowie knife).

Unlike most others of his breed, however, Hickok is remembered as a “good” gunfighter, one who used his six-shooters either in the line of duty to uphold justice or for self-protection in rough places like Kansas’ Hays City and Abilene. Clavin relates Wild Bill’s gunfights rather succinctly (for the details, refer to Rosa), while giving equal time to other aspects of his short, adventure-filled life—his scout and frontier heroics (in the mold of David Crockett and Kit Carson), his association with Buffalo Bill through the years, his stint as a reluctant thespian, his marriage to Agnes Thatcher Lake, his time as a gambler in Cheyenne, later life as a “marked man” with failing eyesight, his relationship (before and after death) with Calamity Jane and, finally, his death in Deadwood at the hands of Jack McCall.

“I sifted through every source I could get my hands on, and at the end of each day a little more gold had been collected in the pan,” Clavin writes in his author’s note. No doubt Rosa had already sifted much of that gold, but readers will find their own riches in Clavin’s prose.

—Editor