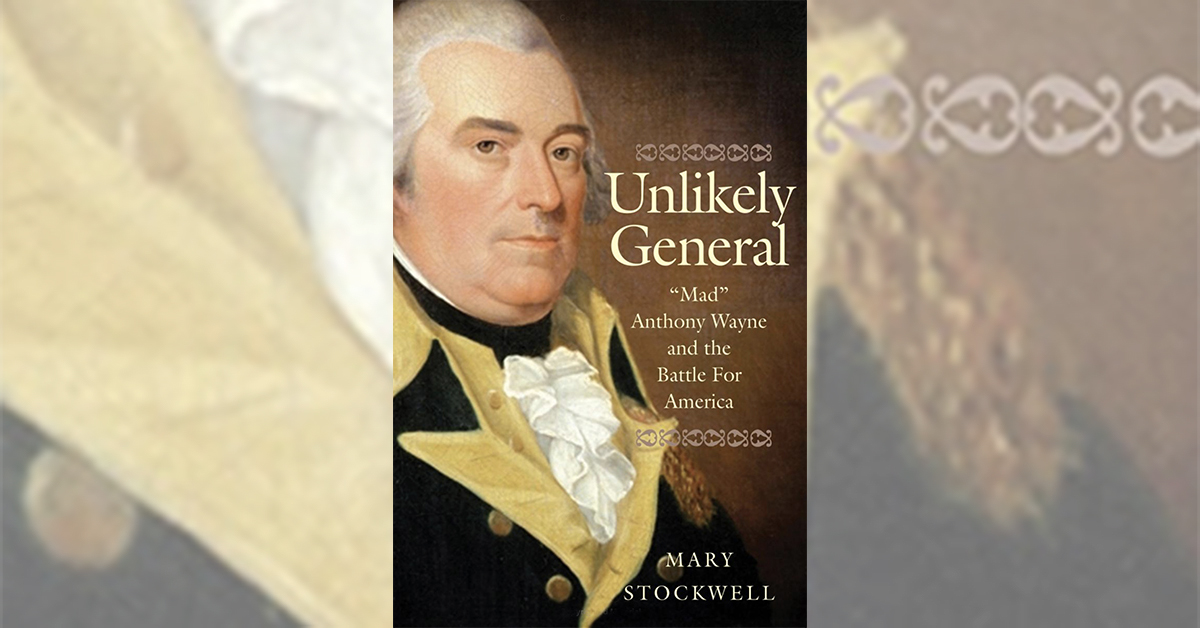

Unlikely General: “Mad” Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America, by Mary Stockwell, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., 2018, $35

The author, former chair of history at Lourdes University in Ohio, delves into the life of Anthony Wayne, the general whose military action against the region’s Indians in the 1790s made the state of Ohio possible. Although Wayne’s personal papers are archived at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Mary Stockwell based her research on the more than 500 letter transcriptions by 19th century historian George Bancroft housed at the New York Public Library. In addition to chapter epigrams of Wayne quotes, she includes an extensive bibliography, detailed endnotes, a dozen illustrations and six excellent maps created by her sister, professional cartographer Roberta Stockwell.

Wayne was a volatile figure known to history by the sobriquet “Mad.” A well-educated man, he quoted Caesar and Shakespeare at length while serving as an officer under Gen. George Washington and befriending Nathanael Greene and Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, during the American Revolutionary War. Wayne was cool under fire and won accolades for his performance at such battles as Brandywine and Stony Point. But he also received due criticism, particularly for the Paoli Massacre, in which British soldiers ambushed Wayne’s camp and granted no quarter to his men. During the Ohio campaign he made many enemies among his fellow officers, notably James Wilkinson and Arthur St. Clair, though he did find a loyal protégé in young William Henry Harrison. An inveterate womanizer, Wayne was estranged from his wife and children.

Though not a well man by then, Wayne achieved the high point of his military career in Ohio, where he masterfully led the new national army, known as the Legion of the United States, after St. Clair led the previous army to destruction in 1791. The responsible Indian confederacy, including the Shawnee, Miami and Delaware tribes—supported by the British from illegally occupied forts at Detroit, Oswego and Niagara—continued to block America’s westward expansion until Wayne’s legion of integrated infantry, riflemen, dragoons and artillery supported by militia broke the tribes at Fallen Timbers on Aug. 20, 1794. His subsequent Treaty of Greenville opened Ohio to settlement, and he presided over the reoccupation of the British forts before his untimely death in 1796.

Stockwell writes cleverly, interweaving time lines of the events of 1791–96 with flashbacks of Wayne’s previous life. Above all, she presents a well-balanced view of settlers and Indians, avoiding the chronic pitfalls of demonizing the one and mythologizing the other. Her worthy biography stands alongside Paul David Nelson’s Anthony Wayne: Soldier of the Early Republic (1985), Alan D. Gaff’s Bayonets in the Wilderness (2004) and William Hogeland’s Autumn of the Black Snake (2017) as the definitive texts.

—William John Shepherd