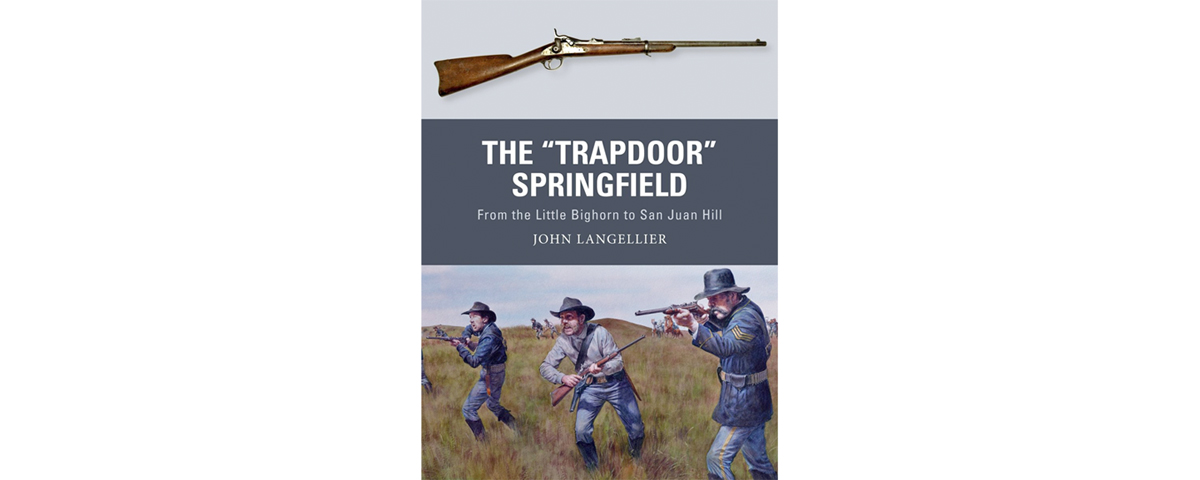

The “Trapdoor” Springfield: From the Little Bighorn to San Juan Hill, by John Langellier, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, U.K., 2018, $20

In 1865 master armorer Erskine Allin of Massachusetts’ Springfield Armory proposed a simple means of improving on his firm’s .58-caliber Model 1861 percussion rifle musket without excessive rework or expense: “All that is necessary is to cut away the barrel on the top at the breech and add the block and shell extractor, cut the recess in the breech-screw and modify the hammer,” Allin wrote. “All other parts remain the same.” To a U.S. military just emerging from a devastating civil war to resume a relatively small-scale pursuit of “Manifest Destiny” in the Western frontier (or so it hoped), cheap and simple held immense appeal. So did the prospect of having a reliable breechloading long arm that could be loaded in any posture, without having to stand up to ram wad, powder and ball down the barrel. The result—popularly known as the “Trapdoor” Springfield, for the way its breechblock flipped up to eject the shell and take the next round—became the mainstay of the Army for more than 30 years, in both infantry rifle and cavalry carbine form. Its principal adversaries, of course, were the American Indians who “stood in the way” of civilization.

A longtime expert on U.S. military affairs during the Victorian and Edwardian era, John Langellier is in his element focusing volume No. 62 of Osprey’s Weapon series on one of the iconic firearms of its age. One might say the Trapdoor hit the ground running, as it was first fired in anger against Red Cloud’s Lakota warriors in 1866. The author traces its fortunes, as dictated by the men who fired it or those who traded shots with it, throughout the West to the first wars the United States fought overseas—in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. By 1898 the Springfield—rugged, dependable and easy to maintain though it was—had been superseded by the Norwegians’ Krag-Jorgensen bolt-action rifle and outclassed by the Spaniards’ Mauser Model 1893. Yet it soldiered on with Volunteer and National Guard units before being phased out of military service and into the waiting arms of collectors.

Langellier evaluates the weapon over its career, comparing it to rival arms and debunking the oft-made claim it was responsible for the 1876 debacle at the Little Bighorn. He also debunks the accuracy rifles generally seem to display in Western films, noting Indians were not well versed in gun sights, especially when firing from a galloping horse, while soldiers on frontier duty had little opportunity to practice their marksmanship. They were allotted only so many cartridges, after which they had to obtain their own at a government rate of 25 cents each, which could add up on a private’s measly salary of $13 a month.

Accompanying the text is an interesting array of progressive variations on the Trapdoor theme, including one used by Oglala Lakota Chief Kicking Bear, who effectively repaired its fractured stock using rawhide and brass tacks. Technical illustrations by Alan Gilliland and artwork by Steve Noon round out a keeper for any Western firearm enthusiast.

—Jon Guttman