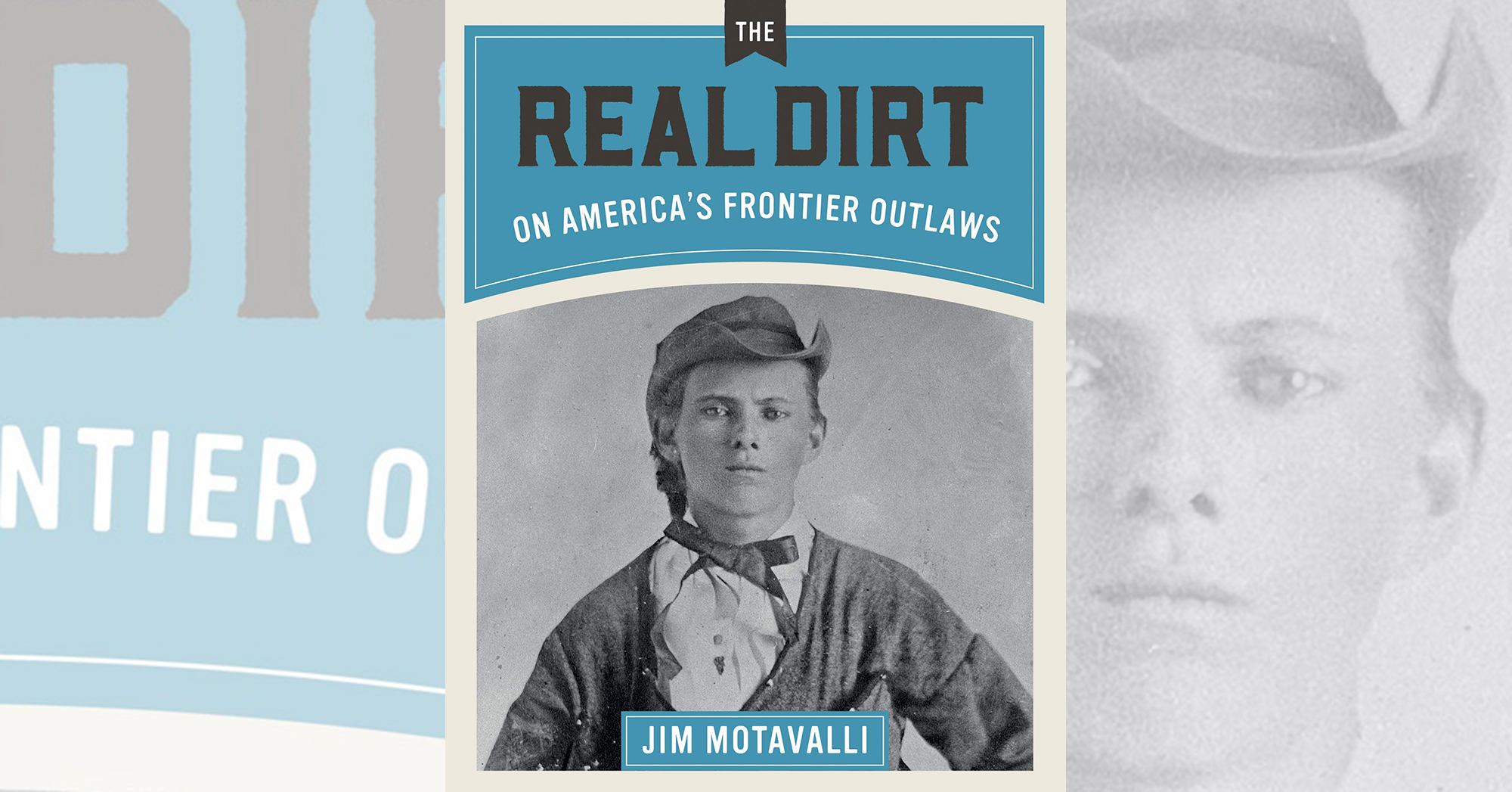

The Real Dirt on America’s Frontier Outlaws, by Jim Motavalli, Gibbs Smith, Layton, Utah, 2020, $24.99

With regard to badmen of the Old West, it goes without saying plenty of real dirt is attached to them. But the title is keeping in line with Jim Motavalli’s earlier offering, The Real Dirt on America’s Frontier Legends (reviewed in the June 2020 Wild West). As our regular readers know, the list of frontier outlaws is extensive, so the author had to be selective in these 240 pages. He managed to cover more than a dozen desperadoes in the longer entries and adds a handful more in his last chapter, “Other Owlhoots and Unsavory Characters.”

It’s not exactly news Jesse James was no noble outlaw, though some people today still hold that notion. The author subtitles his James chapter “Refighting the Civil War” and concedes, “The brutalities of that war turned the onetime young Southern guerrilla “into something of a monster,” but suggests, “It requires contortions to turn figures like Jesse James into heroes, but those contortions were most definitely made in the postwar South.” When it came to killings after the Civil War, though, Jesse (and probably nobody else) was a match for John Wesley Hardin, whose chapter here is subtitled “Revenge for the War of Northern Aggression.” At one point in his evil endeavors, Hardin hooked up with cousin Simp Dixon, a young member of the Ku Klux Klan who swore “to kill Yankee soldiers as long as he lived.”

Hardin tried to justify his murders (“I didn’t kill anyone who didn’t need killing,” he said), but he clearly was always ready to pull the trigger. Naturally Hardin made himself look decent in his autobiography, but Motavalli says the Texan “was in actuality a vicious killer and avid racist.”

Jesse’s rival for best-known Wild West outlaw, Billy the Kid (“The Irish Enigma”), gets full coverage here, as do Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (“Made by the Movies”), Black Bart (“A Gentleman Bandit”) and Johnny Ringo (“A Gunman Who Died Mysteriously”). But less publicized outlaws also get their due, including the wonderfully named Hoodoo Brown (“Bad Hat with a Star”) and such minority miscreants as Isom Dart (“Rodeos and Stock Theft”), the bloody Espinosas (“Early Serial Killers”), Cherokee Bill (“A Killing Spree”) and the Rufus Buck Gang (“Multiracial Rampage”).

The ladies aren’t neglected, either, although celebrity stage robber Pearl Hart’s celebrity was based on only one botched stagecoach robbery. “A female bandit was a novelty, so Hart was much attended and photographed by the press,” Motavalli writes. The so-called bandit queen, Belle Starr, was more a lover of outlaws than a hardened criminal herself. “The legend of Belle Starr was built in the pages of the Naitonal Police Gazette, which had a hand in creating our shared folklore,” the author writes.

The others cited in the closing chapter are Deacon Jim Miller, Dan Bogan, Bill Longley, Tom “Black Jack” Ketchum, the Dalton Gang, Soapy Smith and Belle Siddons. Readers will no doubt think of outlaws left out of the mix, but we can at least enjoy Motavalli’s entertaining treatment of this bunch of baddies.

—Editor

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.