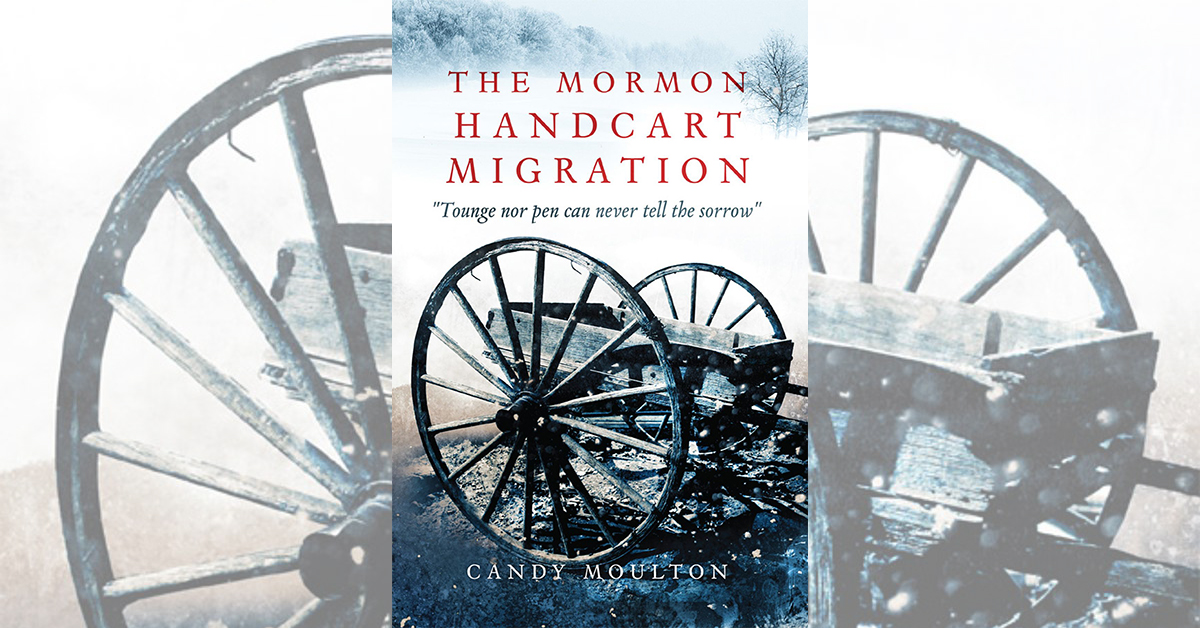

The Mormon Handcart Migration: “Tongue nor Pen Can Never Tell the Sorrow,” by Candy Moulton, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla., 2019, $29.95

Imagine going west by wagon train in 1856, 13 years before you could do that by railroad. Aside from the sheer distance, you must also contend with the treeless Great Plains, Rocky Mountain ascents, difficult river crossings, blistering heat, high winds, drenching rain, early snowstorms, mud-clogged wheels, food shortages, boredom, accidents, breakdowns and fear of the unknown. Looks like a major challenge, right? At least a team of oxen or mules is pulling your wagon full of food and beloved belongings. Now imagine tackling the same trail without a wagon and with far less food and only a few belongings packed into a handcart that you, a two-legged beast of burden, are pulling or pushing. An exhausting vision for sure, and a terrifying one as well, if you see the trail ahead is only getting tougher, the food about to run out and a mid-October snow beginning to fall.

Pioneering companies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (aka Mormons) had arrived by wagon train in what would become Utah in July 1847. Thousands of Mormon converts in the British Isles and Europe were called to emigrate to the United States and make the long journey to Great Salt Lake City. By 1856 LDS leader Brigham Young was calling for converts to reach Zion using hand-drawn carts, which Young said would allow the migrants to come “just as quick, if not quicker, and much cheaper” than by wagon train. That first year nearly 2,000 Mormons in five companies set out with handcarts on a 1,100-mile journey from Florence, Neb., toward Great Salt Lake City. The first, second and third companies all made good time on their overland treks but found out the carts couldn’t carry sufficient food—and all that pulling and pushing by hungry people took its toll. Some died en route. But what was still to come was far, far worse. The fourth and fifth companies departed too late in the season but believed (encouraged by various LDS leaders) their faith would protect them from early snows. Disaster ensued. James G. Willie’s fourth company of 503 individuals saw 66 to 77 members die on the trail, and Edward Martin’s fifth company of 646 individuals lost from 135 to 150.

Young organized the rescue teams sent east to aid these two companies, but according to author Candy Moulton, he only exacerbated the situation by shifting some of the resources from Martin’s company to aid a wagon train hauling church freight. “With ever-greater determination to deflect blame to others,” Moulton writes, “Young declared: ‘Are those people in the frost and snow by my doings? No, my skirts are clear of their blood, God knows.’” He did not deem the handcart experiment a failure. Another five companies would make the trip, the last two in 1860. Only the tenth company recorded no deaths. In all, close to 3,000 people traveled to Utah by these “two-wheeled torture devices,” and between 250 and 300 of them died. Moulton quotes from the diaries of those who made the journey, recording both the good and the bad. One of them, John Chislett, blamed Young for the misfortunes, writing, “But the sad results of his Hand Cart scheme will call for a day of reckoning in the future which he cannot evade.” Elizabeth Sermon lost her husband en route. “Food could have suited us better [than preaching], for we did not think all together about religion,” she recalled, “but my faith was still in my Father in Heaven. I have never lost my faith in Him.”

Moulton, who wrote the feature “Mormon Handcart Horrors” in the December 2014 Wild West (online at HistoryNet.com), has a better idea than most of what it was like to push and pull a handcart those many miles. In 1997 she filed stories for the Casper Star-Tribune while traveling the Mormon Trail from Winter Quarters to Salt Lake City as part of the Mormon Trail Sesquicentennial Wagon Train. Her book delivers a detailed look at the two 1856 handcart tragedies, which had their share of heroism, and provides a comprehensive picture of the entire extremely challenging handcart migration.

—Editor