The Monitor Chronicles, edited by William Marvel, Simon and Schuster, New York, 212-698-7541, 267 pages, $35.00.

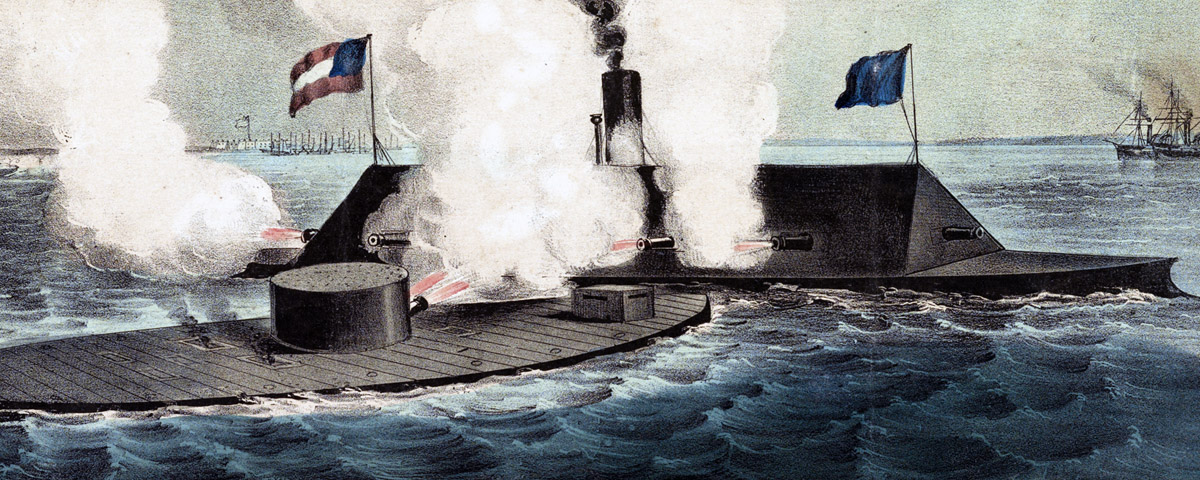

No engagement of the Civil War had greater implications for naval warfare than the March 1862 clash between the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Virginia (the former U.S.S. Merrimack, by which name she is still best known. Yet comparatively little has been published about life on the famous Union ironclad, in part because she was in service for less than a year.

The Monitor Chronicles is essentially a hybrid. The first nine chapters quote and comment on letters from the Monitor by fireman George Geer, a 25-year-old native of Troy, New York, who enlisted in the U.S. Navy in the hope of learning a useful trade. The 10th, and final, chapter describes the ongoing campaign to salvage portions of the Monitor, a project in which the sponsor of this book, the Mariners’ Museum, is actively engaged.

But the heart of the book is the Geer correspondence. Virtually all the letters are from Geer to his wife, and, alas, there is no account of the battle with the Merrimack. Geer, who had carried ammunition to the turret during the battle, wrote Martha that evening that he was safe but tired; she would have to learn of the engagement from the newspapers!

The fact that he was an actor in a great drama was largely lost on Geer. When President Abraham Lincoln visited his favorite ironclad in May 1862, Geer described the visit in a single sentence, writing, “The President was here yesterday and was very much pleased with the looks of our craft.”

Nevertheless, Geer was one of only about 20 sailors who served on the Monitor for her entire 10-month existence, and his letters tell much about life on the vessel. In a letter dated May 20, 1862, he offers a detailed description of a typical day on board. Here is a brief excerpt:

On Sunday as every other day, the Boatswain’s shrill whistle is herd at six, and every body must turn out and lash their Hammock up and stow them away. All hands make their way on deck, get a pail when their turn comes, and have a good wash….

Breakfast…consists of a Pot of Coffee and hard crackers, such as I gave you a sample of…. Our Cook takes those crackers and brakes them up, puts some fat Pork in it (of which we have plenty, as it is so fat no one can eat it), puts salt and Pepper in, and cooks it until the crackers are soft, and that makes what we hungry men call a good Breakfast….

After Breakfast, every thing is cleaned up about the Ship, which takes about one hour, and after that there is nothing to do but keep watch, which amounts to laying about deck for the saylors and laying arund the Engine room for the Firemen.

The letters Geer wrote to Martha tells quite a bit about what motivated him. On one hand, he was a devoted husband, who worked hard to keep his wife in funds. (So parsimonious was the U.S. Navy that Geer often had difficulty getting the pay owed to him.) At the same time, he was less devoted to the Union cause than many soldiers and sailors. When life on board the Monitor became both boring and uncomfortable–temperatures belowdecks exceeded 120 degrees in the summer–George ruminated in his letters about deserting.

Geer had no interest in slavery one way or the other, and as the war went on, his respect for the Rebels increased. In December 1862 he confessed to Martha that “I am getting half Secesh.” He wrote:

I am satisfide we are only wasting life and property for nothing. We will have to declair their independance, I am affrade, after all. In fact, I think after the time they have held their own they are entitled to their independance.

Geer’s letters provide interesting insights into cliques within the Monitor’s crew, which included a large number of Irish immigrants. Geer’s best friend aboard the ship was a Mason, like Geer, and a member of the nativist Know-Nothing party. At one point George wrote to Martha, “I am Sorry to say, that amongst our Crew of 40 there is only 8 of us American born.”

Remarkably, the Monitor had four skippers in her brief career, and Geer had strong views about most of them. He most admired Lieutenant John L. Worden, who commanded the ironclad in the battle against the Merrimack, but found his successor, Lieutenant William Jeffers, “a regular old growler, always finding fault.”

Although historian William Marvel’s connective text for the Geer correspondence is skillfully done, the book is marred by several design problems. Most of the illustrations are tiny; a panoramic view of New York City, for instance, not only seems irrelevant to the text, but also is too small to be effective. Where Geer’s actual letters are shown, they are so small as to be unreadable; as if to compensate, portions of the correspondence are reproduced in a secretarial script that bears no resemblance to Geer’s own hand.

Still, this collection of letters will appeal to readers interested in life aboard the Civil War’s most famous ironclad. Geer survived the sinking of the Monitor in a storm off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. In his last letter to Martha, from the vessel that had rescued him and many shipmates, Geer wrote, “I am sorry to have to write you that we have lost the Monitor, and what is worse we had 16 poor fellows drowned. I can tell you I thank God my life is spaired.”

The final chapter describes the state of salvage work on the Monitor, which rests upside down in 230 feet of water, the hull badly deteriorated. The ship’s anchor has been found and recovered; what else may be recovered is by no means clear.

John M. Taylor

McLean, Virginia