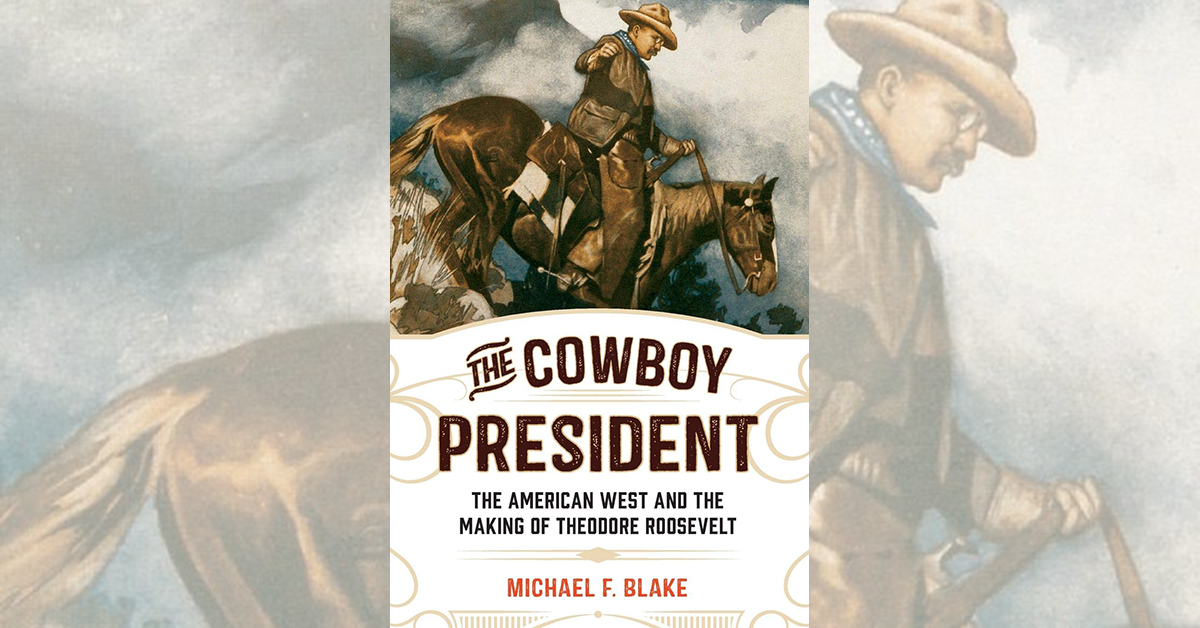

The Cowboy President: The American West and the Making of Theodore Roosevelt, by Michael F. Blake, TwoDot, Guilford, Conn., and Helena, Mont., 2018, $16.95

Theodore Roosevelt might still have become the 26th president of the United States had he not hunted and worked cattle in Dakota Territory in the 1880s, but one could easily argue otherwise. There is no doubt the American West, particularly the Dakotas, transformed Roosevelt. Much, of course, has been written about this charismatic man who, before he became president, served as New York City police commissioner, New York governor, assistant secretary of the Navy and leader of the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. “Lost in many of these texts,” writes longtime Roosevelt admirer Michael Blake, “is how and where Theodore, the reedy dude from New York, became the Theodore Roosevelt who gazes down at us from Mount Rushmore.” It was in Dakota Territory, the author suggests, Roosevelt learned to carry a big stick and when to use it as well as the importance of conservation. “The West,” Blake writes, “would shape him, his policies and, eventually, a nation.”

After his wife, Alice, and mother died within hours of one another in the family’s Manhattan home on Valentine’s Day 1884, the widower went to Dakota to overcome his grief and strengthen his body. He became hooked. Roosevelt spent much of his days in the saddle making his way through the remote and rugged Badlands, enjoying not only the hunting trips but also herding cattle and camping out under the stars. Later, when taking a break from the presidency (1901–09), he returned to the West. “The Badlands, Yellowstone and Yosemite,” writes Blake, “allowed him to reconnect with what mattered most to him and brought him great joy.” The cowboy code—taking pride in your work, your word being your bond, being tough but fair, doing the right thing, which included never being bought—was one Roosevelt admired and tried to live by even when in Washington D.C. His sense of justice was strong. In the “Mingusville affair” he thrashed a bully who called him “Four Eyes,” and he later arrested three men who had stolen his boat, traveling more than 300 sleepless miles to deliver his prisoners.

Roosevelt loved the thrill of the hunt but also led the fight to protect America’s native species, including birds and bison. He established 18 national monuments, five national parks and 51 federal bird reserves and created or expanded 150 national forests, but he also built Roosevelt Dam in Arizona and other dams for reclamation. “There was an interesting dichotomy in Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation efforts,” writes Blake. “He saw nothing wrong in carving out an area for a dam that would provide irrigation for hundreds, if not thousands, of acres for growing crops. However, where those dams were built was just as important to him. He would not allow a dam in, or near, an area that would spoil natural beauty.” What the “Cowboy President” who didn’t like being called “Teddy” ultimately did was preserve 230 million acres, or about half of Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase of 1803. So call Roosevelt the “Conservation President” as well. By whatever name, Blake does him justice in this informative, easy-to-read 296-page book.

—Editor