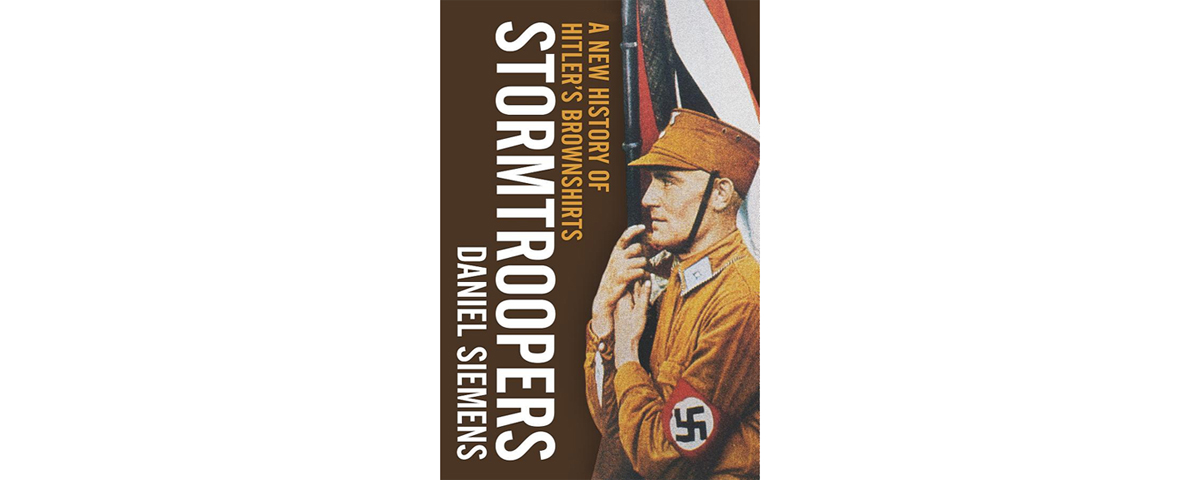

Stormtroopers: A New History of Hitler’s Brownshirts, by Daniel Siemens, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., 2017, $32.50

In pop culture mention of the word Stormtroopers evokes images of the menacing white-clad imperial soldiers immortalized in the Star Wars film franchise. For historians it calls to mind Nazi Führer Adolf Hitler’s Sturmabteilung (SA) thugs, wearing brown shirts, swastika armbands and hobnailed boots as the ugly face of Germany’s Third Reich, among the worst regimes in the sad history of humankind. Author Daniel Siemens, a professor of European history at Newcastle University, claims his is the first comprehensive account of the SA, spanning from 1921 to 1945, whereas most stop at 1934, when Hitler purged the SA leadership in the infamous “Night of the Long Knives.”

Siemens argues the SA was a social movement that used violence and populist appeal to destroy the Weimar Republic and advance the Nazis to political power. Although reined in by Hitler, the SA remained a bulwark of the Third Reich, especially as a feeder of its thousands of individual members into the German military (Wehrmacht). The SA was also active in Eastern Europe, integrating ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) into the Reich, pressuring allied regimes like Slovakia to round up Jews and supporting occupation forces (the Gestapo and SS) in Poland, especially in putting down the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. On the home front SA members engaged in worker education, as air raid wardens and as a last-ditch home guard (Volkssturm) at the bitter end in 1945.

With a mastery of German language archival sources, Siemens presents chapters documented with extensive endnotes and supported by 33 enumerated plates, mostly photographs but also drawings and posters, though sans a bibliography, glossary or appendices. He convincingly makes a provocative case SA members successfully downplayed their post-1934 role as a legal defense during the postwar military tribunals of Nuremberg, enabling many of them to avoid punishment and also fueling the largely mythic notion of the “Good German”—a simple patriot and not an ardent Nazi. While prone to jargon (i.e., the “microsociology of violence”) and not easily accessible to the general reader, this diligent study should remain required reading for years to come.

—William John Shepherd