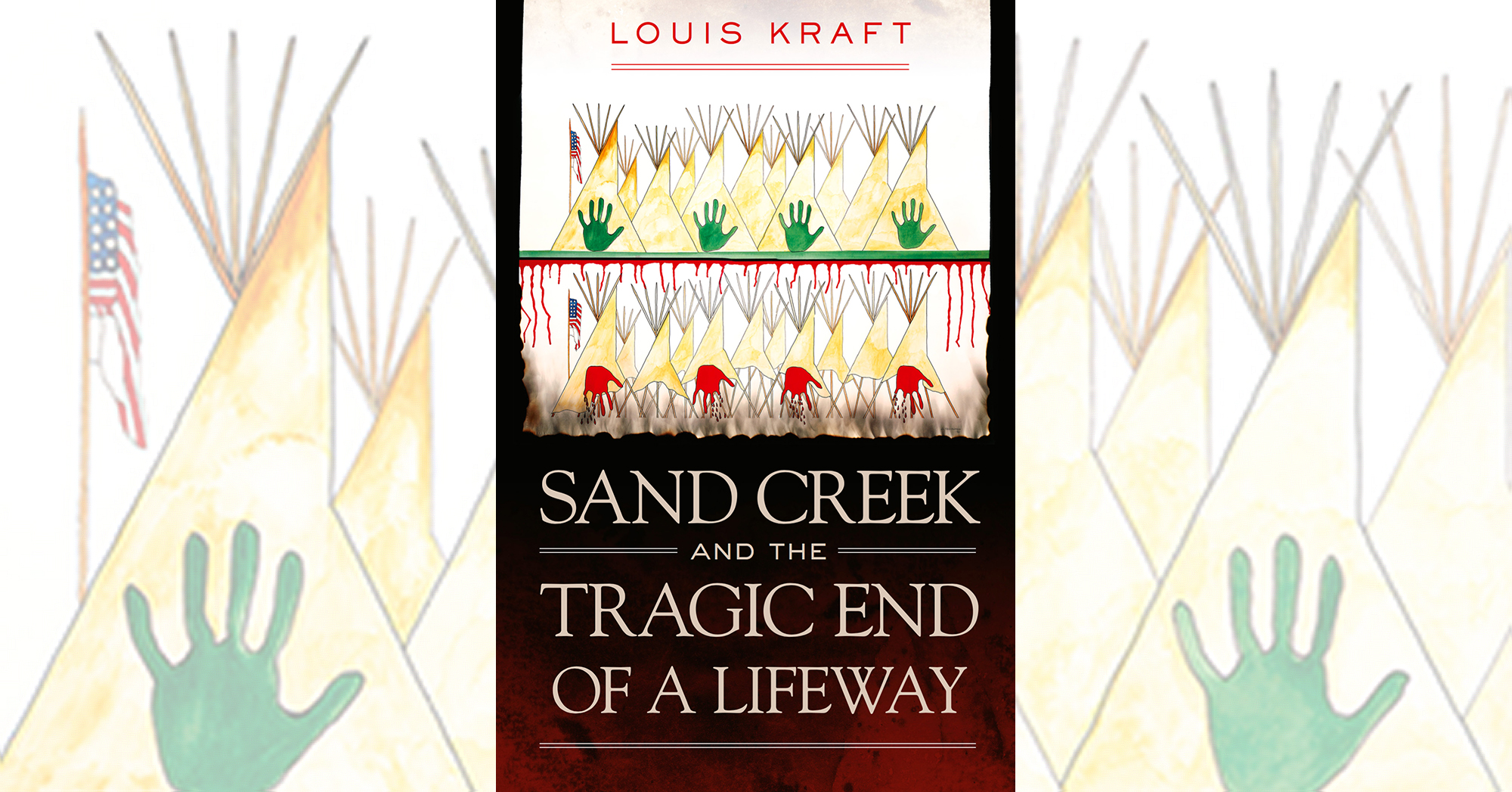

Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway, by Louis Kraft, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2020, $34.95

Louis Kraft has written many articles for Wild West and other publications, as well as seven books, including the 2011 biography Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road From Sand Creek. One of his favorite figures on the Western frontier remains Wynkoop, the Army officer who among other things tried to bring about peace before the Nov. 29, 1864, tragedy in Colorado Territory known as the Sand Creek massacre. Wynkoop receives plenty more attention in Kraft’s most ambitious work to date, but the focus of this well-researched book is on the destruction of the way of life of the Cheyennes (Tsitsistas) and Arapahos (Hinono’eino), who took a major hit when Colonel John Chivington attacked and destroyed the village of Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle at Sand Creek. Though Chivington called the engagement a battle, he resigned from the Army three months later and was condemned for what one Army judge called “a cowardly and cold-blooded slaughter.”

Black Kettle, a chief who wanted peace, survived Sand Creek but was killed when Lt. Col. George Custer attacked his village on the Washita in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) on Nov. 27, 1868. In the aftermath Custer managed to avoid further bloodshed when he held back his soldiers and convinced Cheyenne Chief Stone Forehead to surrender after a dramatic standoff (detailed in Kraft’s October 1998 Wild West article “Confrontation on the Sweetwater”). “More likely his decision not to attack—his shining moment on the plains—mimicked Chivington’s,” Kraft notes, “in that he held the power to release two armies on a people, two armies that craved blood, but chose not to butcher children, women and men.” There was more fighting up north, but Chief Tall Bull was killed at Summit Springs in July 1869, and the next month the Southern Cheyennes and Southern Arapahos were settled on the reservation at El Reno in Indian Territory. “Only a few Southern Tsitsista and Hinono’eino leaders survived the deliberate destruction of their people’s freedom and were herded onto their reservation in Indian Territory that none of them wanted,” the author writes. “In a little more than two decades these once-proud people—the rulers of the central plains—had lost everything and had been reduced to paupers and prisoners in a foreign land.”

Among the characters in Kraft’s well-crafted history are the prominent Indian leaders Black Kettle, Stone Forehead, Tall Bull, Bull Bear, Little Raven and Little Robe, as well as such mixed-bloods as the sons of William Bent and Edmund Guerrier. The author does not neglect the whites involved in this often-sad story. Colorado Territory Governor John Evans, who took a harsh stance against the Indians he thought were threatening Denver, comes across as misguided but not as bad as sometimes portrayed. Rocky Mountain News editor William Byers, a staunch defender of the anti-Indian vision of Chivington and Evans, might be considered a “villain” in Kraft’s narrative, which is far more than simply another retelling of the horrific tragedy at Sand Creek.

—Editor

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.