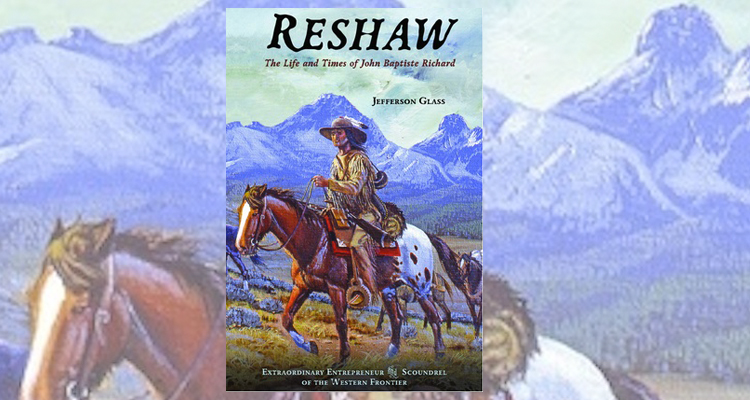

Reshaw: The Life and Times of John Baptiste Richard, Extraordinary Entrepreneur and Scoundrel of the Western Frontier, by Jefferson Glass, High Plains Press, Glendo, Wyo., 2014, $19.95

Talk about your unsung Westerners. John Baptiste Richard (“Reshaw” was a common variation of his surname) was a frontier entrepreneur involved in fur trading, freighting, whiskey smuggling, bridge and ferry construction, trading posts, ranching and raising livestock. Much of his varied activity (“John Richard was not a man to keep all of his eggs in one basket,” writes author Jefferson Glass) took place in the vicinity of Fort William/John/Laramie, on the North Platte River in present-day Wyoming. He is perhaps best known for spanning that river in 1853 with a substantial structure that became known as Reshaw’s (or Richard’s) Bridge and then charging Oregon Trail emigrants and freighters—as many diarists attest—varying toll rates. “As the water in the North Platte River rose,” writes Glass, “so did the toll, and so did Richard’s reported financial investment in the bridge.” A small settlement (60 to 100 civilian residents, along with various military and Indian encampments) grew up next to the sturdy bridge, and early Bozeman Trail traffic in 1864 departed the Oregon Trail from the vicinity. But in the winter of 1865–66, while Richard was away, the command at the growing Fort Caspar dismantled the bridge and several adjacent buildings to provide much needed firewood.

The author lives in Evansville, Wyo., a few hundred yards from the site of Reshaw’s Bridge, and was naturally first interested in that historic location before becoming intrigued by the man behind the bridge. Historians can be thankful he decided to research John Richard, as his largely overlooked life story is compelling. The toll bridge is only part of the picture. Richard (1810–1875) had a series of successes and failures as a trapper and trader; his ability to bounce back and launch new ventures made him stand out among his peers. “The whole man wore an air of mingled hardihood and buoyancy,” wrote historian Francis Parkman, who in June 1846 invited John and Mary Richard to join his hunting party for coffee along the Platte. Richard was a man of contradictions. A skilled and ruthless barterer, he was not above smuggling contraband whiskey into the northern Plains and trading it to Indians. “Given the opportunity, he would trade white man, Indian, friend or foe out of everything he owned,” writes Glass. Away from the bargaining table, though, Richard was often generous and compassionate, willing to share food and shelter and knowledge of the region with newcomers and those down on their luck. For instance, in the winter of 1856 he butchered several of his oxen and sent them by pack train to men on the verge of starving to death at Devils Gate fort. Richard, the author says, also boasted a few firsts—the first to import food products to trade with the tribes of the northern Plains, and the first to report news of the gold strike on Cherry Creek that triggered the Colorado Gold Rush.

A savior to some and a scoundrel to others, Richard made plenty of money from his commercial ventures but was not a wealthy man when he died a violent and somewhat mysterious death on a lonely trail in late 1875. As the title of the book suggests, Glass covers more than just the life of the main character. Some of the adventures the author relates involve Richard’s family members, including sons John Baptiste Jr. and Louis, and friends, such as prominent scouts/interpreters Baptiste “Little Bat” Garnier and Baptiste “Big Bat” Pourier. The story of John Richard, his family, friends and enemies will delight anyone interested in the spirit of the Wild West or the spirits (alcohol) so much in demand by white men and Indians alike. As Glass concludes, “John Richard influenced the development of nearly every phase of the economy in frontier West.”

—Editor