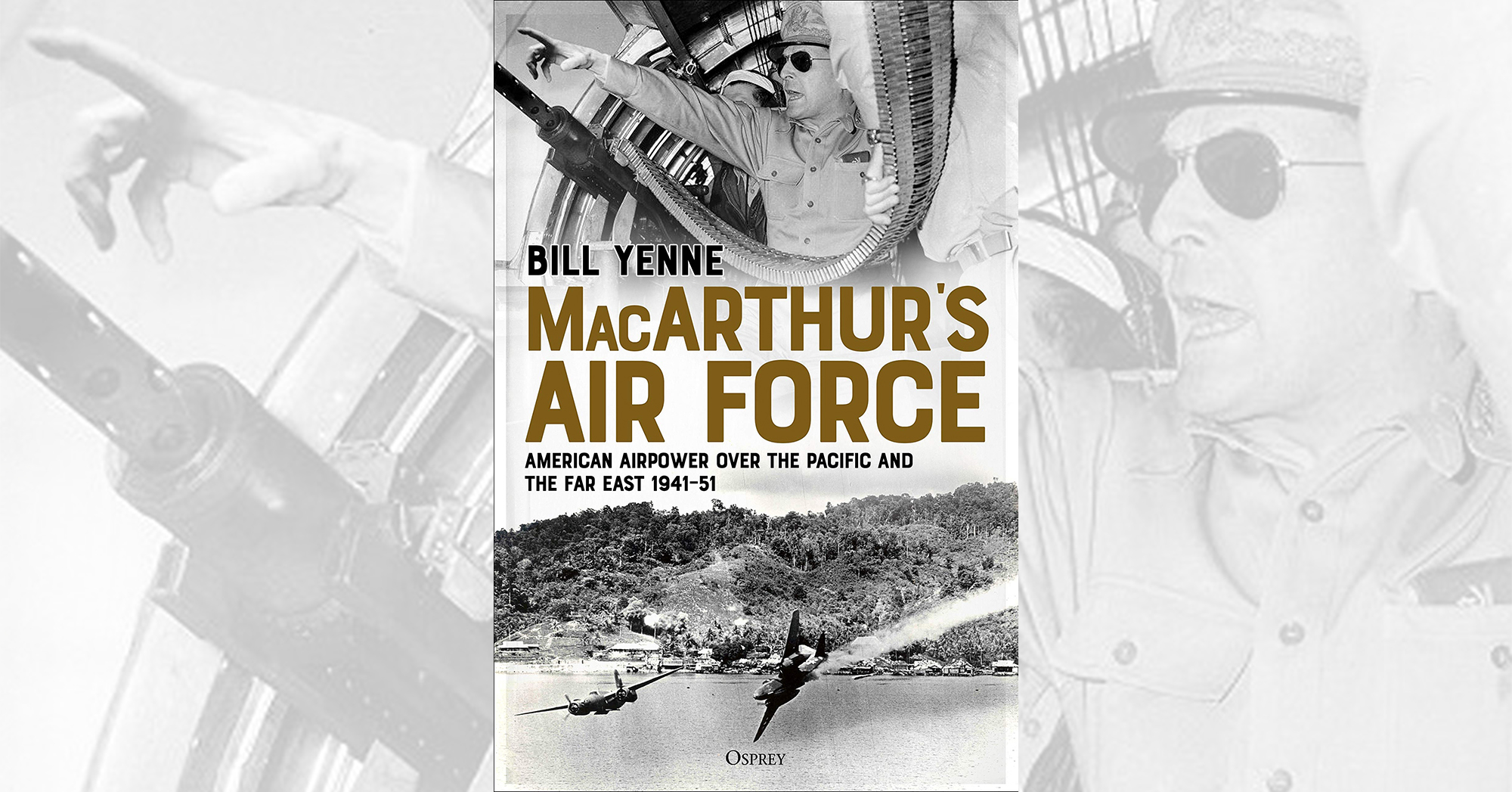

MacArthur’s Air Force: American Airpower Over the Pacific and the Far East, 1941–1951, by Bill Yenne, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, U.K., 2019, $30

In the latter conflicts of his 61-year military career—the Pacific Theater of World War II and again in Korea—General of the Armies Douglas MacArthur relied on airpower. But how he wielded the flying sword via his various airmen has seldom been explored in the manner of Bill Yenne’s latest volume.

Opening with MacArthur’s 1941 debacle in the Philippines, Yenne cites contradictory accounts of how U.S. airpower in the region was largely destroyed over two hours on December 8, following the headline-grabbing events across the International Date Line. The author makes a convincing argument that the enduring mystery exists in part due to “incomplete memories of participants with much to forget.”

In the aftermath MacArthur turned to Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force, as his foremost air commander. Having come up in attack aviation, Kenney was relatively new to heavy bombardment, but his command excelled in the tactical use of twin-engine bombers, notably North American B-25 Mitchells and Douglas A-20 Havocs. From New Guinea in 1942 to the Philippines in 1944 his aircrews set a high standard of innovative effectiveness against Japanese ground and sea targets.

New units joined Kenney’s command, which eventually expanded into the Far East Air Force and included the Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces. Much of Yenne’s narrative describes the comings and goings of various bomber, fighter and transport groups and their affiliated personalities, notably Col. Paul “Pappy” Gunn, father of the B-25 gunship. Chapters trace the rise and fall of leading aces, as Kenney was determined that by war’s end the American ace of aces would be a man from his command. He got his way with U.S. Army Air Forces Maj. Richard Bong, though in the process he expended some fine leaders, men the caliber of Thomas J. Lynch, Neel E. Kearby and Thomas B. McGuire Jr.

At war’s end MacArthur’s prestige rode the peak of his power as a Pacific supremo. He remained in theater between the wars, overseeing Japan’s demilitarization until confronted with a crisis by North Korea’s attack southward in June 1950. Yenne examines the waning fortunes that led to MacArthur’s humiliating 1951 dismissal by President Harry Truman. But it is not excessive to say that airpower saved South Korea during MacArthur’s tenure.

Throughout, Yenne provides a detailed, objective assessment of how the controversial general alternately used and misused airpower via his successive flying commanders. In that regard, MacArthur’s Air Force likely will become a standard reference.

—Barrett Tillman