Historians have long debated whether the Civil War was history’s last Napoleonic-style conflict or a prototype of how war would be fought in the 20th century. Major General William T. Sherman has often been characterized as the U.S. Army’s first practitioner of modern warfare. Now Harold Knudsen makes a case for Lt. Gen. James Longstreet as his Confederate counterpart. As a 25-year army veteran well-versed in modern warfare planning and tactical operations, Knudsen makes an articulate and persuasive case.

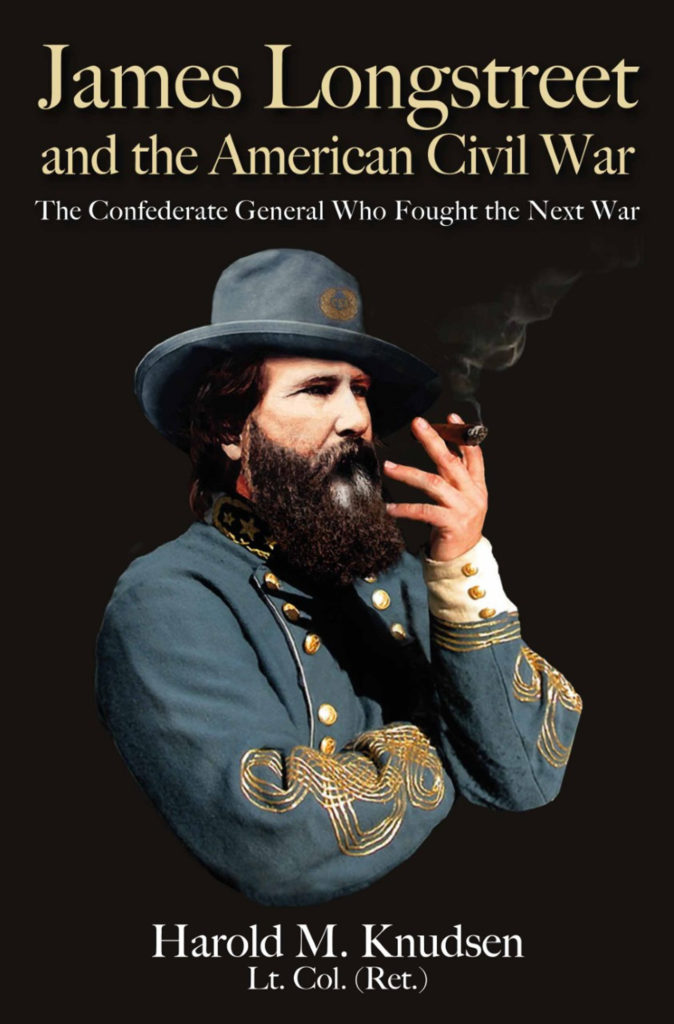

Knudsen’s book is not a biography of Longstreet nor an analysis of his postwar political transformation that made him a whipping boy for Lost Cause ideologues. Rather, his purpose is “an examination of Longstreet from the vantage point of modern methods that set him apart from his contemporaries.” Knudsen concludes that Old Pete “made such adjustments to the known tactics, techniques, and procedures of his day and proved that his adjustments were decisive modernizations in nineteenth century warfare.”

Longstreet began to practice modern tactical warfare, Knudsen maintains, early in the Peninsula Campaign. At the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, Knudsen credits Longstreet as being “responsible for fixing the enemy, seeing to the safe passage of the army’s trains, and maintaining situational awareness of the larger picture.” He also had misgivings about Lee’s strategy at Malvern Hill, an attack on a strong Union defensive position that cost the Confederacy more than 5,000 casualties.

During the Antietam Campaign, Longstreet “advocated a concentration of Confederate forces to lure the Union army into a large battle on ground of Lee’s choosing and avoid smaller engagements that carried no chance of significant results.” Nevertheless, Lee, a bold albeit traditional tactician and strategist, opted to contest the South Mountain gaps. Later, at the Sunken Road, Longstreet learned that “the prepared tactical defense was dominant over the direct tactical offense;” a lesson he would advantageously employ at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Knudsen is critical of Lee’s decision for a second invasion of the North, concluding, “Failure to set a campaign objective sealed Lee’s defeat in Pennsylvania.” His incisive, non-ideological analysis of the campaign culminating in the Battle of Gettysburg starkly contrasts the ways Lee and Longstreet viewed tactical and strategic military operations. Knudsen closely examines each day’s events and concludes “Lee tried to force a win in a situation that probably would not have occurred at all if he had declared an attainable and politically profitable objective before the campaign began.”

Knudsen follows Longstreet west where he led the Confederate breakthrough at the Battle of Chickamauga while butting heads over tactics with General Braxton Bragg. There, Knudsen maintains “with minimal planning time, Longstreet had orchestrated a masterstroke on a scale like none yet executed in the war” while showing himself “as much a master of the offense as the defense.”

Critics of Knudsen’s analysis of Longstreet’s military acumen can point to the author’s lack of analysis of the general’s leadership when in overall command of operations that failed to capture the Union garrison at Suffolk, Va., between April 11-May 4, 1863; the author’s attributing Longstreet’s defeat at Knoxville in November 1863 to poor performance by subordinates; and giving short shrift to his role as Lee’s most reliable corps commander during the 1864 Overland Campaign, the siege of Petersburg, and the final days of the Army of Northern Virginia prior to its surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

Knudsen’s monograph will surely revive the Lee vs. Longstreet debate among amateur strategists, professional historians, and Lost Cause die-hards. In conclusion, Knudsen opines that “On the corps level he was the only one of the Confederate side who innovated on a large scale —and therefore Longstreet deserves recognition as the Confederacy’s most modern general.” Readers are given ample information to decide for themselves.

James Longstreet and the American Civil War

The Confederate General Who Fought the Next War

By Harold M. Knudsen, Savas Beatie, 2022

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.