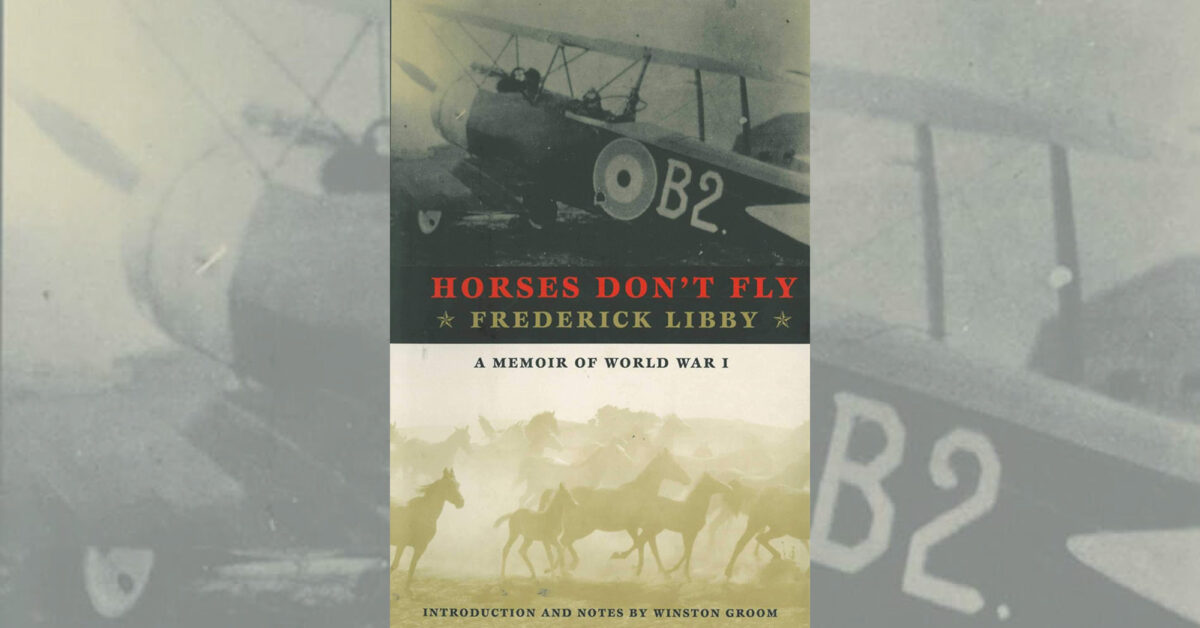

Horses Don’t Fly: A Memoir of World War I, by Frederick Libby, Arcade Publishing, New York, 2000, $25.95.

The original application of the airplane in war was to penetrate enemy lines to gather intelligence, essentially taking over the role of light cavalry. It should be hardly surprising, then, that some of the best pilots of World War I were accomplished horsemen–some of whom, in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), still wore spurs as a standard part of their uniforms in 1914. Several of these pioneering fliers had had their previous equestrian experience in the American West, including Frank Luke, Jr., from Arizona, “Wild Bill” Ponder from Oklahoma and Frederick Libby from Colorado.

Fred Libby died in 1970, leaving behind a lively memoir of his wartime service that has finally been published 30 years later. Almost half of Horses Don’t Fly deals with his childhood on his father’s ranch in Sterling, Colo., and how he grew up to enjoy a rough-and-ready life in the American Southwest.

Libby was looking for work in Canada when World War I broke out, and he volunteered for British service. After a few months in the trenches, he requested a transfer into the RFC in 1915, serving as an observer and gunner in F.E.2bs with Nos. 23 and 11 squadrons. His horseman’s sense of balance certainly served him well while flying in the front pulpit of the F.E.2b. This aircraft was a pusher that required the observer to deal with attacks from the rear by standing up and manning a Lewis machine gun mounted on a pole to fire back over the upper wings. On August 25, 1916, Libby was credited with his fifth German airplane, making him the first American ace of World War I.

After downing five more enemy planes, he trained as a pilot, going on to score two victories flying with Sopwith 1 1/2-Strutter two-seat fighters in No. 43 Squadron, and two more flying de Havilland DH-4 bombers in No. 25 Squadron. Tragically, Libby’s military career was cut short not by enemy bullets, but by illness. He suffered circulation and spinal impairment after returning to the States and joining the U.S. Army Air Service (USAS). As a result, he was left a cripple for the rest of his life. True to form, however, Libby remarked upon resigning from the USAS: “What I am going to do, I don’t know, but I want to be free to do it, if only selling pencils on the corner.”

Horses Don’t Fly is an engaging first-hand account that documents the end of one era and the beginning of another, by a man who managed to make the transition with remarkable success. As such, it should appeal as much to scholars of the Old West as to World War I aviation buffs.

Jon Guttman