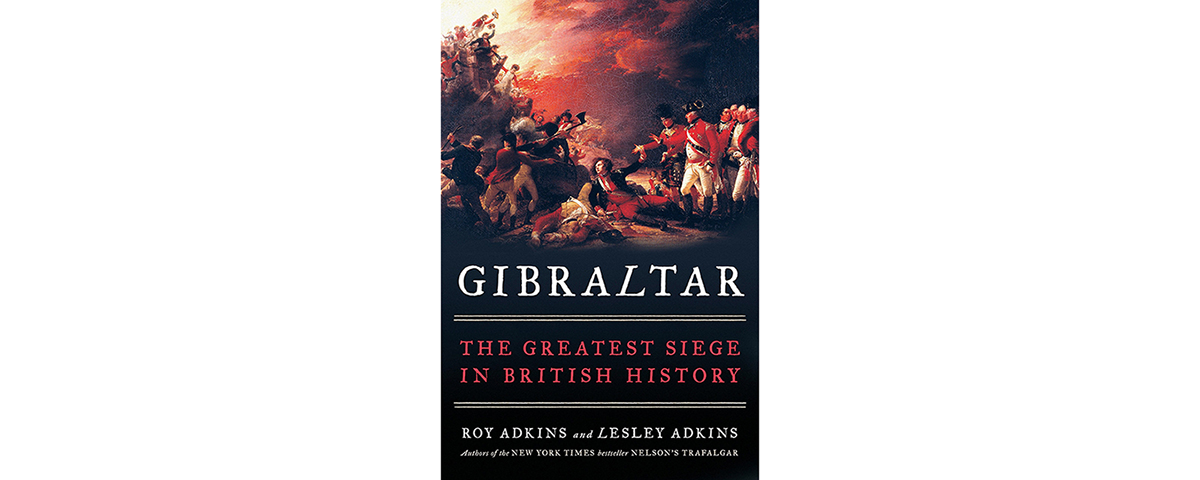

Gibraltar: The Greatest Siege in British History, by Roy and Lesley Adkins, Viking, New York, 2018, $30

It may surprise students of American history to learn that one of the most strategically important campaigns of the Revolutionary War was conducted on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean—in fact, in the Mediterranean Sea. British authors and archaeologists Roy and Lesley Adkins relate the story of that extraordinary campaign in their book.

Linked to Spain from the 15th century, Gibraltar first came under British control during the 1701–13 War of the Spanish Succession, when fear of French King Louis XIV induced much of Europe to forcibly oppose transfer of the Spanish throne to a member of the French royal House of Bourbon. In 1704 an Anglo-Dutch fleet captured Gibraltar, which was ceded to Britain nine years later in exchange for its withdrawal from the conflict. Desire to regain control of the port factored into Spain’s military and diplomatic strategies for the remainder of that century. After more than seven decades of failed efforts the Spanish government thought it finally saw its chance when rebellion broke out in Britain’s North American colonies. Hoping to humble their long-standing rival, the Bourbon monarchies of Spain and France allied with the rebels.

The opportunistic motivations behind their support for American independence became manifest when the Bourbon allies placed Gibraltar under siege in 1779. But their plans to exploit a distracted Britain backfired. Yes, the siege crippled the Crown’s war efforts in North America, but the men, supplies, money and ships Britain was forced to divert to the Mediterranean only assured its victory in the three-and-a-half-year siege. When the dust settled in 1783, the American colonies were independent, Gibraltar remained part of the British empire, the French government was bankrupt and Spain’s decline as a world power continued unabated.

The authors provide superb context regarding the siege, drawing on firsthand accounts and touching on military innovations developed during the protracted campaign. Just as fascinating is their analysis of its political aftermath, during which many Britons almost certainly wondered whether their government had allowed 13 colonies to become independent merely to retain a single port.

—James Baresel