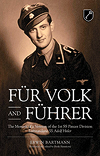

Für Volk and Führer: The Memoir of a Veteran of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, by Erwin Bartmann, Helion & Co., Solihull, United Kingdom, 2013, $49.95

No student of modern military history can afford to ignore the Waffen-SS. First, there is the organization’s unique, bewildering and essentially ad hoc structure, from its origin as Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard to its expansion into Heinrich Himmler’s paramilitary police and prison service, a National Socialist foreign legion and, finally, the Third Reich’s fourth armed force. Second, several units within the Waffen-SS, notably the components of I and II SS Panzer Corps, constituted a military elite that saw an unparalleled amount of action during their existence. The Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) was not only the initial formation of the Waffen-SS but also one of the divisions with the most distinguished combat record. The late Corporal Erwin Bartmann’s memoir of his service with the unit is a significant contribution to English-language accounts of the German war experience.

Bartmann’s account is highly personal, and as it is presented entirely in his words (as translated and edited by his friend Derik Hammond), there is little to connect the series of incidents he describes with the role of either the LSSAH or the larger formations of which it was a part. For anyone who lacks detailed prior knowledge, the absence of editorial notes or an appendix will make the narrative of Bartmann’s tours of duty confusing. That prompts another criticism: Bartmann served in the LSSAH from May 1941 to May 1945, but he was wounded in July 1943, spent 17 months recovering and finished the war as an instructor at the LSSAH’s training and replacement battalion at Spreenhagen. This itself is not problematic—Bartmann saw plenty of combat during his operational service—but that service occupies less than half the volume, and the final two weeks of the war, during which Bartmann was with Regiment Falke (apparently part of V SS Mountain Corps) rather than the main elements of the LSSAH, constitute the lion’s share of the action.

As such, the subtitle—while strictly accurate—is somewhat misleading, and although the book provides valuable insight into the day-to-day life and mentality of an LSSAH soldier, it is really more of a social than military history. Bartmann’s tale is ultimately tragic, an example of what can happen when young, impressionable men fall under the spell of a charismatic psychopath whose ethos promotes casual inhumanity and lasting remorselessness.

—Rafe McGregor