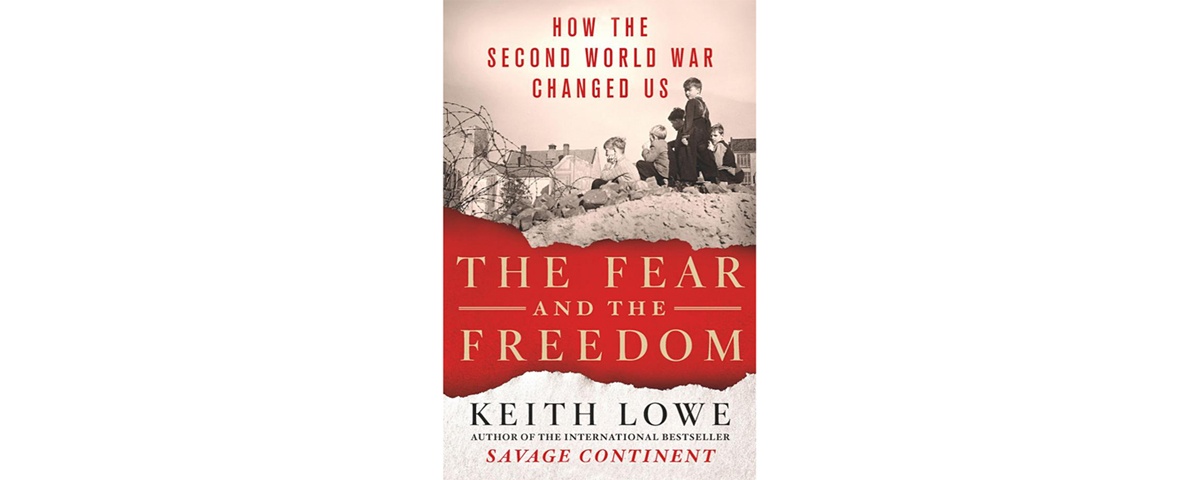

The Fear and the Freedom: How the Second World War Changed Us, by Keith Lowe, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2017, $29.99

World War II claimed some 60 million lives, altered borders, brought about the fall of empires and ultimately left an indelible imprint on the latter half of the 20th century. Historians have related the ghastly scenes of the Holocaust and the dramas of D-Day and Dunkirk since the events themselves took place. Yet despite the vast historiography on the subject, historian Keith Lowe argues that analysis of the effects of the war, both immediate and long-term, is rare indeed.

With this volume Lowe relates just how much we still live in the war’s long shadow. Along the way he challenges notions that the conflict was the last just war, and that the Allies were always the noble heroes they are portrayed to be. He also examines the false hope that advances in science and political liberties made possible by the war would somehow lead to idyllic, peaceful societies. Lowe chronicles the formation of the United Nations and European Union as attempts at a one world society, attempts that ultimately failed due to the political polarization of the Cold War. The author charts the monumental task of managing the refugee crisis brought about by the war, the postwar nuclear threat and the regulation of the world’s financial system by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. He also examines such positive effects as women in France winning the right to vote in 1946, and President Harry S. Truman ending segregation in the U.S. Army two years later.

World War II undoubtedly triggered seismic political and social changes. Yet Lowe’s chain of historic causality is limited. He repeatedly cites connections from the late 1930s and ’40s to the present, yet shies away from any consideration that flash points with far earlier origins may also have had a major impact on events during and after the war. For instance, when discussing the 1990s breakup of Yugoslavia, he cites ethnic divides among the Balkan people during World War II but does not acknowledge how events dating back to ancient Rome helped foster such divides. Lowe also overlooks more recent drivers, such as World War I, as well as how such postwar events as natural disasters influenced people and governments.

—Jeff Davis