CHINA’S WINGS

CHINA’S WINGS

War, Intrigue, Romance, and Adventure

in the Middle Kingdom During the Golden Age of Flight

By Gregory Crouch. 528 pp.

Bantam, 2012. $30.

The Shangri-La-ish dust jacket and breathless subtitle of China’s Wings make it seem like a potboiler, but it is a first-rate saga of aviation, wartime politics, and business that manages to be gripping without sacrificing scholarly rigor.

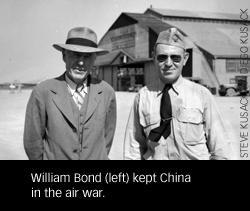

The setting is China, where the war began in 1931—or 1937 at the latest. Famous figures such as Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-shek, airline mogul Juan Trippe, “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, and Claire Chennault have important walk-on parts, but China’s Wings stars William Langhorne Bond. Bond journeyed to China in 1931 to seek his fortune and ended up as head of the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), a joint venture between Curtiss Wright (replaced in 1933 by Pan Am) and the Chinese Nationalist government. It became one of the most remarkable airlines of the era, uniting a far-flung country by drastically cutting travel times. Bond’s success with CNAC stemmed from several factors: his conviction that the Chinese employees were partners instead of servants, his ability to grasp the intricacies of doing business in China, and his natural diplomatic skills.

Under Bond’s steady hand, CNAC prospered, even though his Chinese government partners did not reciprocate his diplomacy, treating their American collaborators with suspicion and disdain. Relations grew so strained that Bond wore a shoulder-holstered Colt .45 to one meeting. Yet he faced new challenges with the outbreak of open Japanese aggression against China in 1937. Japanese fighters shot down a fully laden CNAC plane with heavy loss of life. A CNAC Douglas DC-3 transport lost a wing to a Japanese bombing attack; fitted with a much shorter replacement wing from a DC-2, it was dubbed the DC-2 ½. CNAC often flouted the rules out of necessity; it is hard to find a case where a CNAC flight didn’t depart seriously overloaded or with non-standard components. In December 1941, China’s war became global, and CNAC lost nearly half its fleet in the Japanese attack on Hong Kong. Nevertheless, the airline “got off the mat” and resumed operations more quickly than did many Western military organizations in the Far East. After all, CNAC had been on a war footing for four and a half years. (For more on Pan Am during the war years, see “Juan Trippe’s World” by John D. Lukacs, September/October 2011).

The plucky airline’s tale then merges with the larger story of the American war effort in the China-Burma-India Theater. CNAC flew supplies for Chennault’s Flying Tigers, and pioneered flying supplies from India to China in what later evolved into the famed “Hump” airlift. Not surprisingly, relations between CNAC and the U.S. Army Air Forces were frosty; the experienced China hands bested the newcomers in every measure of effectiveness. Still, Crouch notes, the heroic flights over the Himalayas actually did little to bolster the Chinese fight against Japan (partly because Chiang was more interested in fighting the Communists) while bleeding resources from the European Theater.

The plucky airline’s tale then merges with the larger story of the American war effort in the China-Burma-India Theater. CNAC flew supplies for Chennault’s Flying Tigers, and pioneered flying supplies from India to China in what later evolved into the famed “Hump” airlift. Not surprisingly, relations between CNAC and the U.S. Army Air Forces were frosty; the experienced China hands bested the newcomers in every measure of effectiveness. Still, Crouch notes, the heroic flights over the Himalayas actually did little to bolster the Chinese fight against Japan (partly because Chiang was more interested in fighting the Communists) while bleeding resources from the European Theater.

Unlike many Allied World War II stories, this one did not end in triumph. Although CNAC more than earned its keep, Bond (who earlier had strong-armed Trippe into persisting with the China venture) saw the writing on the wall. His health broken, his illusions about the Chinese Nationalist Party shattered by the political murder of a close friend and a growing awareness of the regime’s incompetence and corruption, Bond worked to disentangle Pan Am from CNAC. The 1949 Communist victory brought CNAC’s dissolution.

Some richly detailed accounts here might seem too good to be true, but Crouch has impeccable sources. Bond was an inveterate letter-writer, a diligent filer of reports, and a memoirist. His account of the evacuation of Hong Kong, written only days after the disaster, was so powerful it was widely disseminated within the State and Treasury Departments. CNAC’s pilots also filled in the documentary record, leaving archival materials that Crouch uses extraordinarily effectively. He interviewed the dwindling band of survivors—like 99-year-old Moon Fun Chin, who rose from humble peasant origins to become one of CNAC’s pilots, eventually running his own airline—and their families. All this fuels Crouch’s compelling narrative and makes China’s Wings an exceedingly appealing combination of adventure story, aviation and military history, and earthy travelogue.