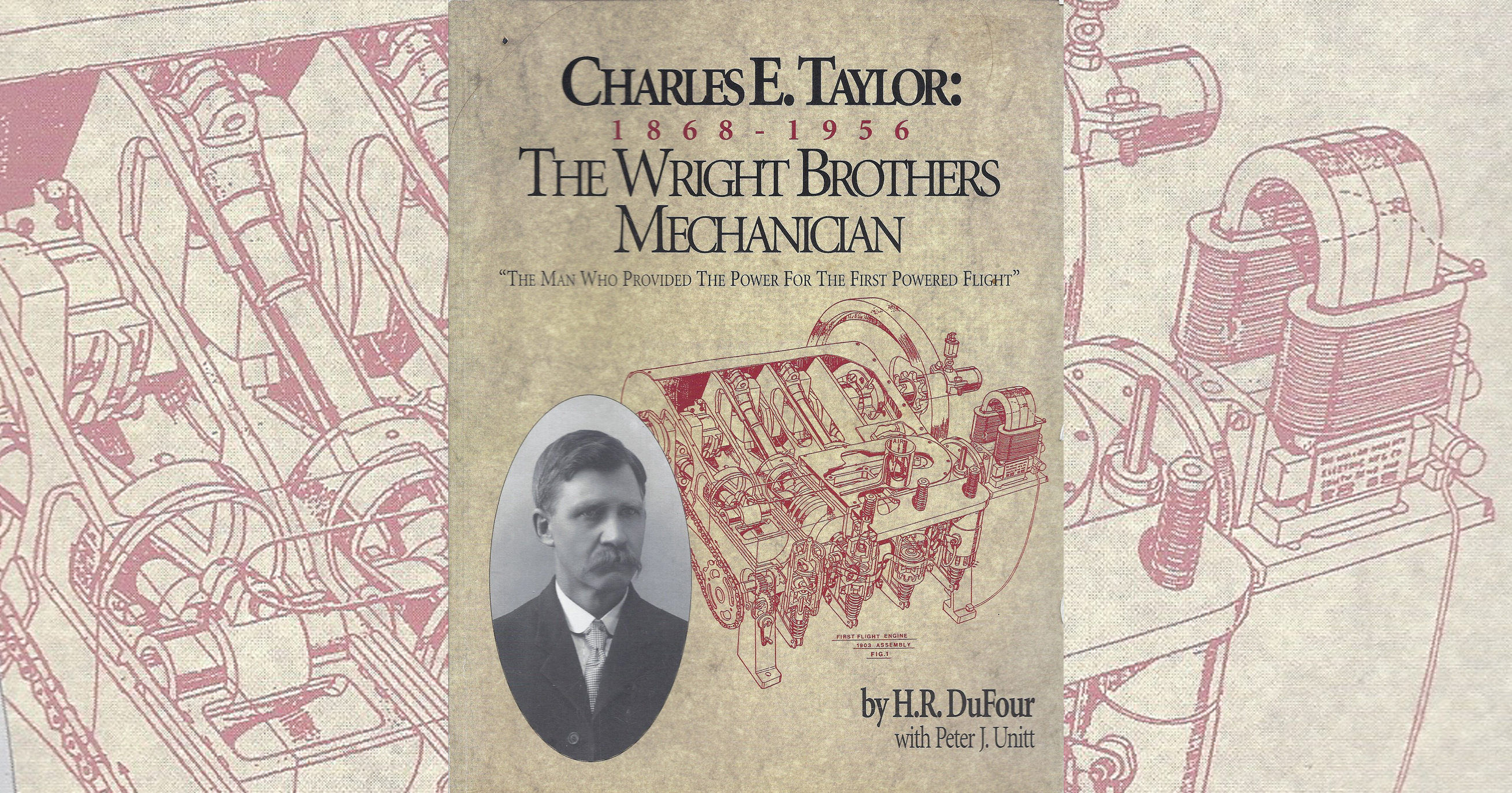

Charles E. Taylor: The Wright Brothers’ Mechanician, by Howard R. DuFour with Peter J. Unitt, available by mail order only from Prime Printing, 1270 North Fairfield Road, Dayton, Ohio 45432-2600, hardbound $34.95, softbound $24.95, plus $3 shipping.

That’s right–the word is “mechanician,” which we nowadays shorten to mechanic. But Charles Taylor was much more than your run-of-the-mill engine fiddler. He built from scratch the engine that provided the oomph to keep the Wright Flyer in the air–the power for the first man-carrying, controlled, powered flight. He milled the pieces, turned the cylinder holes on a lathe and put it all together. And it ran.

On that mid-December day on the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright experienced no engine problems. What Charles E. Taylor did with metal and machinery significantly contributed to the success of the famous brothers who contributed the aerodynamic and structural research and development–and who were first to take the airplane into the sky.

I learned about this fascinating book from an Aviation History reader who advised me that he had just heard “a wonderful presentation” by Howard DuFour, who had written a book about the Wright brothers’ mechanician. I talked with H.R. DuFour, who turned out to be a lively and fascinating character, and he sent me a copy of the book to review. Look for a feature article by DuFour about Charles E. Taylor in our November 2003 issue, when we will commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Wright brothers’ December 17, 1903, flight at Kitty Hawk.

According to DuFour, his book on Taylor was a 14-year labor of love. Along the way, the author collected photos, drawings, engine pieces and tools, as well as the reminiscences of individuals who remembered parts of the story.

Taylor, who was hired by the Wrights in 1901, built not only the engine for the Wright Flyer that made the first flight in 1903 but also engines for the 1904 and 1905 airplanes–the latter, called the first practical airplane, flew the first passenger. He was also the Wright’s chief mechanic and was in charge of maintenance at the Wright Flying School at Dayton’s Huffman Prairie, where many early aviators learned to fly.

He spent seven weeks of 1911 following Calbraith P. “Cal” Rodgers along his legendary coast-to-coast flight in the Wright Model EX airplane. Taylor kept the engine running despite the many crash landings that punctuated the 49-day trip from the East Coast to California.

In 1928 Taylor headed west to live in California and seek other work, but he got socked by the Great Depression, and his fortunes declined. In 1936 he heard that Henry Ford was gathering Wright artifacts to establish a museum in a turn-of-the-century setting in Dearborn, Mich., to be called Greenfield Village. Taylor participated in that endeavor and built yet another engine–a half-scale working model of the 1903 engine for display–among other projects.

Taylor remained active and involved in a variety of projects late in his long life. He outlived the Wright brothers, then basked in the status of being an aviation celebrity until his death at age 88 early in 1956.

In his lifetime, Taylor saw the development of aviation from the dawn of flight to the advent of the space age. His biographer, Howard DuFour, who is himself in his 80s, has said that he feels he and Taylor are kindred spirits. DuFour is a mechanician in his own right, with a background as tool and die maker, machine tool and design engineer and master model maker. His expertise adds immensely to the credibility of the book. His book provides, along with the historical details of Taylor’s life, a variety of photos of aircraft, engines, engine castings and parts, and a fascinating appendix on just how Taylor built the 1903 engine.

If you are interested in machinery and want to machine your own Wright engine replica, the last page of the book explains that you can purchase a set of the 1903 engine drawings from the Wright State University Dunbar Library Archives in Dayton, Ohio.