During World War I, mounted cavalry experienced a brief but turbulent debut on the Western front before the changing nature of the war rendered these traditional European forces all but ineffectual.

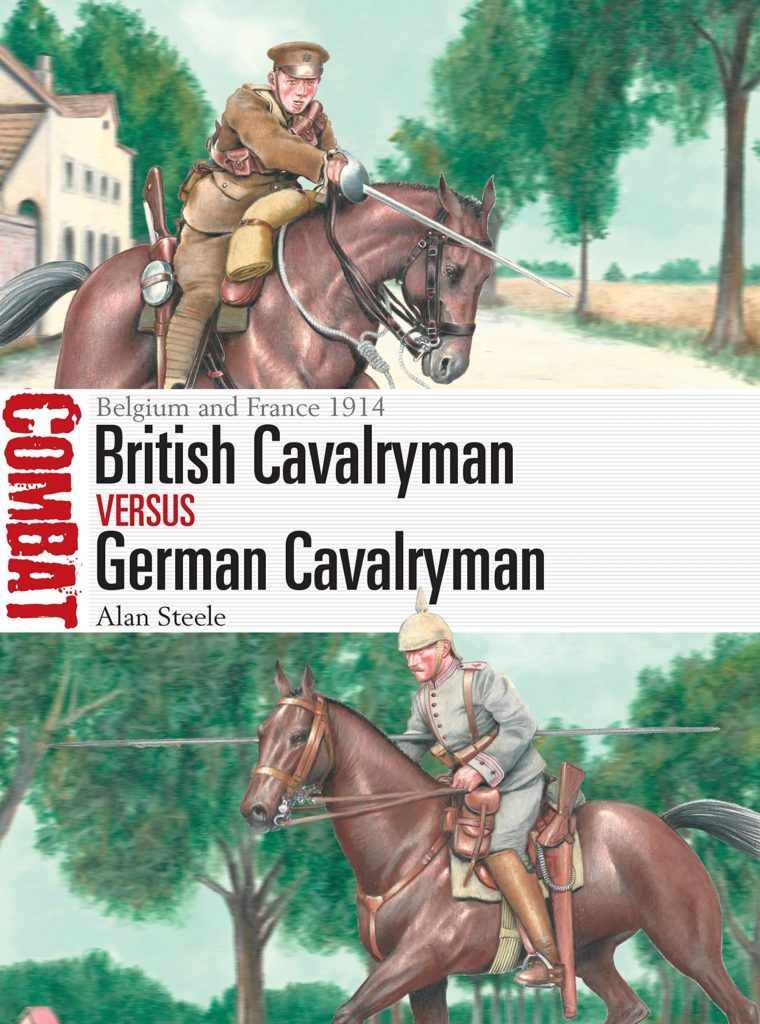

In “British Cavalryman Versus German Cavalryman,” author Alan Steele draws an interesting contrast between the British and German forces facing off against each other on horseback in 1914.

Armies fighting in 1914 expected their cavalry to fulfill the requirements of mobile warfare — scouting, preventing enemy reconnaissance, and following up retreating enemy forces — as armored vehicles had not yet been invented and the use of aircraft on the battlefield was in its infancy at the war’s outset. Steele’s book examines the performance of cavalry units in August and September 1914, covering a wide variety of topics including weapons, tactics, unit reports, logistics, recruitment and morale.

Lances vs. Flexibility

German cavalrymen were expected to do most of their fighting with lances. To reach for a firearm — in this case, the 7.92×57 mm Mauser Karabiner 98AZ (Kar 98AZ) carbine — was understood to be a last resort. Although German horses were extremely well-trained and seemingly well-cared-for in the stables, the horses suffered from neglect in the field. That led to great losses of the animals, and, by 1916, Germany was experiencing a widespread shortage of horses. Additionally, German cavalry had an arguably less nuanced grasp of cavalry tactics, focusing primarily on mounted charges and not training their men for dismounted fighting.

The British took a more holistic approach. Throughout the 19th century, British cavalry troops had learned from fighting in small-scale wars across the British empire that cavalry “had to be flexible in the application of tactics to be able to operate effectively against a wide variety of enemies,” the author notes.

After a nadir in performance in the Boer War, the British cavalry adapted and improved. Particular attention was paid to horsemanship, with each cavalryman “taught to see his horse as his best friend and to consider its needs before his own.” British cavalrymen were trained to maintain their horses’ health in the field and would often march on foot beside their horses to decrease the animals’ burden — astonishing the French, Steele writes. As a consequence of the higher standard of animal care, the British were able to keep their horses in better condition than either the French or the Germans.

“In 1914 the British cavalry probably had the best horsemasters of any cavalry in the world,” according to Steele.

Additionally, the British trained their cavalrymen to use firearms with the same efficacy as the infantry and to fight while dismounted.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Brutal Combat

The book demonstrates that cavalry combat in 1914 was — as it had been for centuries before — bloody and brutal. Men used swords and lances to impale each other. Horses were killed. Men could be trampled. The British Pattern 1908 cavalry sword, designed as a thrusting weapon driven by the momentum of the horse, sometimes caused problems in the field. Lt. Col. Frank Wormald “using a 1912 Officers’ Cavalry Sword, stabbed a German dragoon, but the force of the impact as the sword went through the man’s body buckled the blade, rendering the weapon useless,” Steele writes. By contrast, a British adjutant wielding an outdated Pattern 1896 cavalry sword “managed to cut down five Germans with it” because of its sharper edge.

As troops were drawn into the trenches by late 1914, the cavalry was forced to reconsider its purpose. The Germans all but eliminated the use of cavalry, with some exceptions in Eastern Europe. The British were reluctant to shelve the cavalry entirely and maintained a force on the Western front, although arguably the most notable British cavalry successes during the war occurred in Palestine, Lebanon and Transjordan.

Supplemented by detailed maps and illustrations, Steele has done a thorough job of analyzing unit histories and provides gripping details of battles and actions. However, the narrative does not examine in any great detail the problems faced by the cavalry on the developing Western front that resulted in its twilight in Europe. These factors included the use of mines, barbed wire, machine guns and artillery, in addition to environmental factors such as pitted landscapes and trenches, which made it impossible to use horses in mobile warfare as had been done for ages past. Rendered ineffectual in combat, some cavalry chargers were used as beasts of burden and carried supplies alongside mules and pack horses. Horses continued to have an important role — in transporting supplies across narrow tracks and muddy roads that vehicles could not easily navigate.

Although the British ultimately maintained their tradition of having cavalry units, these were forced to adapt to the changing nature of warfare and, as tanks and armored vehicles came to the fore, could no longer be used as they had been in the past.

British Cavalryman versus German Cavalryman

Belgium and France 1914

by Alan Steele, Osprey Publishing, Aug. 16, 2022

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.