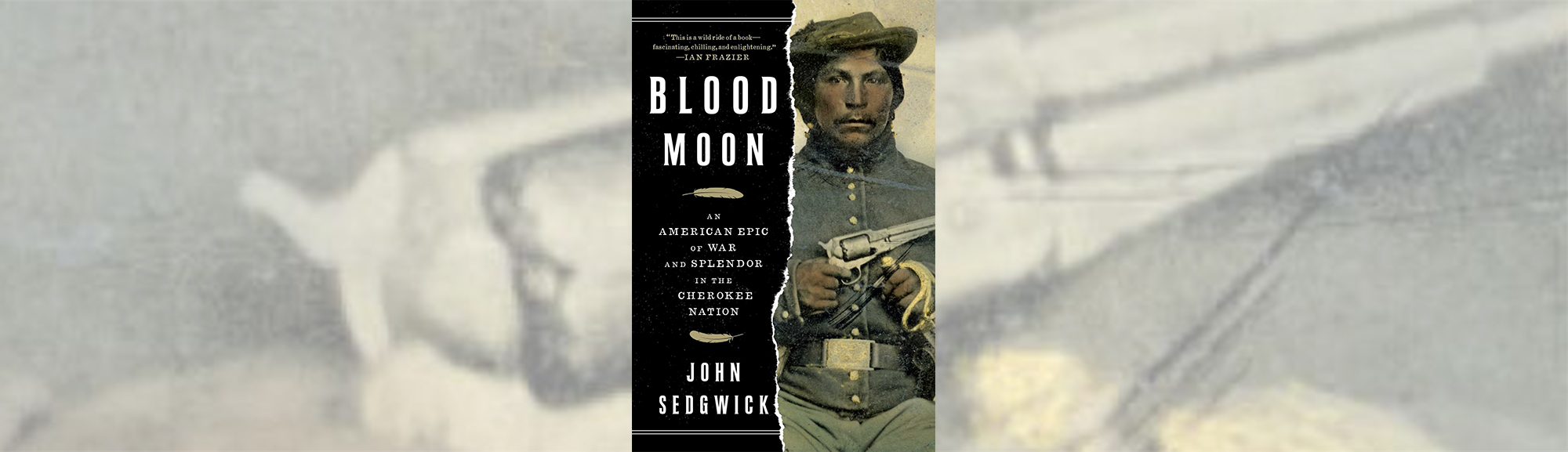

Blood Moon: An American Epic of War and Splendor in the Cherokee Nation, by John Sedgwick, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2018, $30

During the American Civil War the Cherokee Nation was as divided as the United States. Out in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) Stand Watie led his Confederate Cherokees—some of whom owned black slaves—and other Indians against Union forces in guerrilla warfare, as well as a few small battles. John Ross, the principal chief of the Cherokees from 1828 to 1866, wanted neutrality at first, then sided with the Confederacy for largely financial reasons before switching his allegiance to President Abraham Lincoln and the Union. Toward war’s end some of Watie’s men switched allegiance to the Union, while still others, author John Sedgwick writes, “dreamed of murdering the Confederate leadership that had abandoned them.”

As with the broader conflict, the allegiances and enmities were far more complicated, not to mention the Civil War hardly marked the onset of such divisiveness in the Cherokee Nation. In the 18th- and early 19th-century Southeast the Cherokees had their share of conflict with both other tribes and settlers pushing westward. The biggest fights were waged over the issue of removal. While President Andrew Jackson and Georgians didn’t always see eye to eye, they were largely in accord in wanting the Cherokee and the four other Civilized Tribes (Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole) to abandon their homeland and start all over again west of the Mississippi River. It mattered little the Cherokees had their own language, newspapers and government and were considered culturally advanced. The long, painful process of removal (culminating with the wrenching 1830s migration known as the Trail of Tears) was not simply a matter of dispute between the Cherokees and those who wanted Indian land. A simultaneous blood feud erupted in the Cherokee Nation, pitting John Ross (1790–1866) and followers against Major Ridge (1771–1839) and faction.

“The Cherokee Nation did not stand as one against the threat of removal,” Sedgwick writes in his introduction. “It stood as two, one side agreeing that, given the relentless white encroachment, the Cherokee had to go, and the other insisting that they stay forever, come what may.” In his compelling narrative the author relates the behind-the scenes drama of what has been called the “Cherokee Holocaust,” a tribal clash that lasted far too long, as neither Ross nor Ridge was willing to compromise. Sedgwick concludes that given the United States’ might, that the Cherokees inhabited some 125,000 square miles of prime real estate, and that the stronger power believed it was entitled to that land as its manifest destiny, the unspeakable tragedy of removal was probably inevitable.

But what of the rivalry between Ridge, who identified with the prosperous mixed-bloods and signed a treaty to leave for the West, and Ross, who led the full bloods determined to stand their ground in the East? The fracture their heated rivalry created in the Cherokee Nation prompted a series of retaliatory killings that made most other historic feuds in America look like minor disagreements. It didn’t have to happen that way, the author suggests in the epilogue, “and that was the tragedy.”

—Editor