IN THE NEUROLOGICALLY disconnected world of autism there is a spectrum of people—this writer included—who have a degree of social impairment, with the compensation of some exceptional specialized talent: for example, easy mastery of a musical instrument, an expert grasp of math and science, or, as in my case, a knack for remembering historical minutiae. This is unofficially known as Asperger’s syndrome, a term coined in 1981 by British psychiatrist Lorna Wing as a professional courtesy to Austrian psychiatry pioneer Hans Asperger. Although Asperger himself compared notes with Wing “over tea” before his death in 1980, he had only published a few studies since his original paper on the subject in 1944. Now Asperger’s Children, a new book placing his original research in its historical context, offers some disturbing possible reasons why.

Born on February 18, 1906, Hans Asperger grew up in Austria’s Habsburg Empire, worked at the University of Vienna Children’s Hospital in the 1920s, and joined the nation’s Fascist ruling party, the Fatherland Front, in 1934. When Austria was incorporated into Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich in 1938, Asperger was one of many clinicians whose careers benefited from the consequent purge of Jews, who had once constituted 90 percent of Austria’s psychiatric profession.

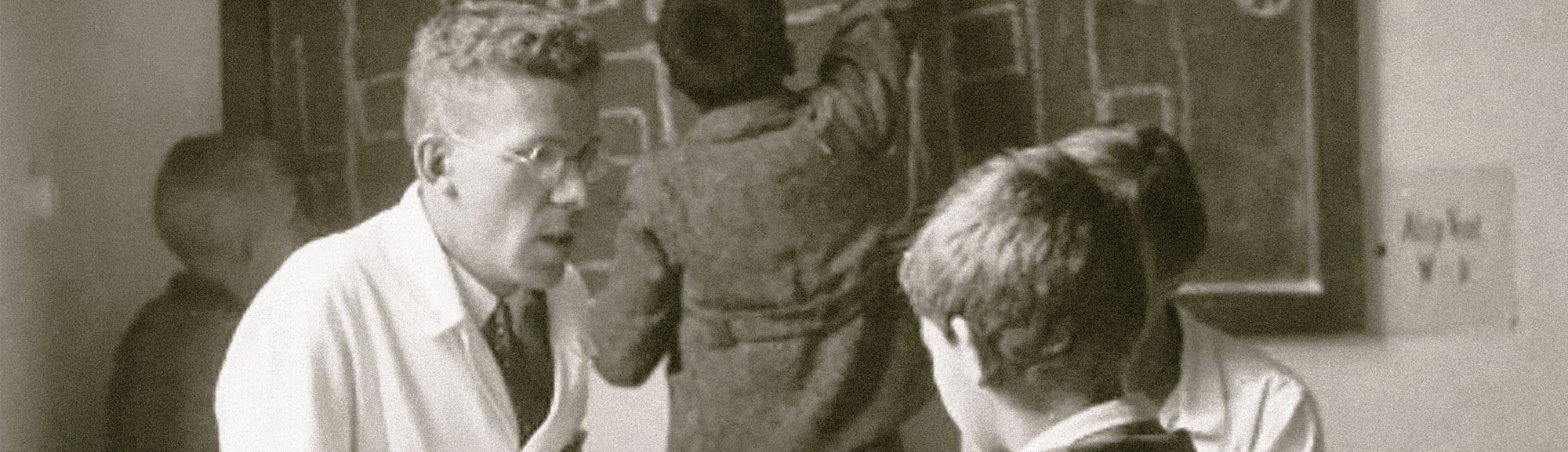

It was also in the Nazis’ New Order that he and his colleagues focused their efforts on children whose “deviant behavior” cast doubt on their ability to conform to the spirit, as well as the physique, of the ideal Aryan. The self-isolation first identified as “autism” by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911 ran starkly counter to that ideal and led to thousands of children being rounded up for examination. Here, Asperger developed his concepts on the individual nature of autistic psychopathy, applying them to balance each child’s degree of detachment against the frequent benefits of extraordinary talents that could be of use to the Reich. In the compound known as the Spiegelgrund, the fate of these children was ultimately determined—either to be released for special care or sterilization or, in hundreds of cases, euthanasia, usually by the deliberate introduction of diseases such as pneumonia or simply by starvation.

Historian Edith Sheffer’s meticulous research into this overlooked aspect of Nazism reconstructs with commendable detachment and restraint the horrors described by the children who survived the terrifying ordeal at Spiegelgrund. Asperger, who alone among his colleagues never officially joined the Nazi Party, never faced a reckoning for his role in the atrocities committed there, and certainly did not mention it while comparing notes with Wing.

Even so, Asperger’s Children leaves readers with a haunting moral question regarding his place in psychiatric history: how many children did his diagnoses save and how many others did they send to their deaths? —Jon Guttman is a World War II magazine historian