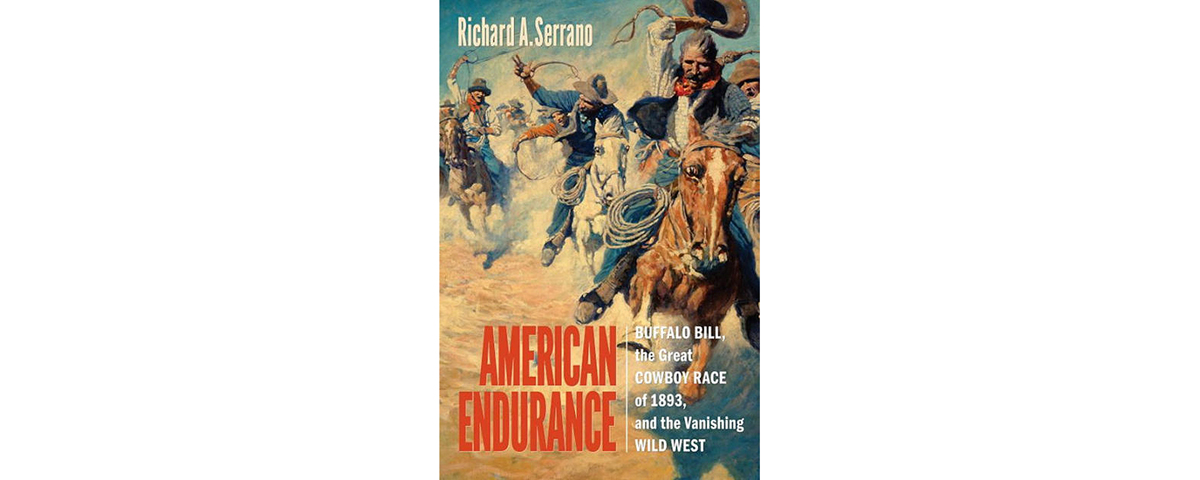

American Endurance: Buffalo Bill, the Great Cowboy Race of 1893 and the Vanishing Wild West, by Richard A. Serrano, Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C., 2016, $27.95

Some stories practically tell themselves. The saga of the Great Cowboy Race of 1893—a 1,000-mile odyssey on horseback from the gumptious frontier town of Chadron, Neb., eastward across the Great Plains and Corn Belt to the bright lights of big-city Chicago—is one such story. It bridges the Old West and the modern era, bringing together chapped cowboys and bowler-wearing dudes, saddle horses and streetcars, Wild West showman Buffalo Bill Cody and prophet of the closing frontier Frederick Jackson Turner. It has all the elements of a natural page-turner without the need for embellishment. Still, it doesn’t hurt to have a Pulitzer Prize–winning writer at the reins.

Newspaperman Richard Serrano does his frontier forebears proud with passages like this breezy lead:

The Great Cowboy Race of 1893 tested a particularly American virtue: endurance. It was launched at the close of the Western frontier and near the start of the new 20th century. Nine men rode leaning over their horses, hats slapping in the wind, defiant symbols of the vanishing Wild West. For two weeks they thundered toward the noisy, crowded, cobblestone metropolis of Chicago and the dazzling White City of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

The race itself had started as a lark. A year earlier a town wag named John Maher had circulated rumors in the press that Chadron boosters were planning a long-distance horse race featuring real cowboys and Western broncos and ending in Chicago in time for the world’s fair. Though town fathers were eager to promote their would-be metropolis, Maher’s boast put them over a barrel. Rather than eat crow, they called a meeting, planned just such a race and then took things a step further, contacting Buffalo Bill and proposing his show grounds as the ideal finish line. It helped their cause that Cody had a score to settle.

“Cody wanted his Wild West to share the glory and profits of the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition,” Serrano explains. “Where else did he belong, if not to the world? But the fair said no. Cody represented the past, the old Western world; the fair would be about the future. So Buffalo Bill leased a large tract of land next to the fairgrounds and was soon outdrawing the fair itself.”

Jumping at the chance to further boost ticket sales, Cody threw in with the race promoters and personally put up a $500 purse for the winning rider. Colt Arms soon joined the bandwagon, offering a gold-plated revolver with ivory grips as a prize, while Montgomery Ward donated a fine leather saddle. Even as the excitement built among promoters, their backers and Western townspeople, word of the proposed race inflamed delicate Eastern sensibilities, particularly those of animal welfare proponents. The latter tried every means possible to kill the “cruel contest” in its planning stages before settling for inspection stations along the route and their stamp of approval, or disapproval, at the finish line. Nine riders—including notorious outlaw Doc Middleton and race route planner John Berry, a non-cowboy who rode under protest—persisted through the planning stages and overwrought protests to post time.

“And so the cowboys raced,” Serrano recounts. “Their mission was to stay focused in the saddle and to win the race. Or at least to make it to Chicago. Or if not that, to one day tell their grandsons driving gas-choking tin cans in some crowded big city that they had once sat atop a living, breathing mortal being in the greatest adventure of their long lives. That for two weeks of one short, glorious summer across Nebraska, Iowa and Illinois and two mighty rivers, they had endured the challenge of a lifetime.”

On Tuesday, June 27, 1893, thousands of curious Chicagoans, fairgoers and tourists surged along the city’s cobblestone streets after a lone rider, “stooped and spent, clinging to his saddle horn, swaying but bravely hanging on to his horse.” But to learn his identity and the rest of the story, you’ll have to line up and buy a ticket like everyone else.

—Dave Lauterborn