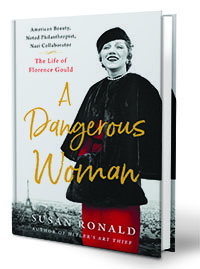

By Susan Ronald. 400 pp. St. Martin’s Press, 2018. $27.9

OFTEN THE MOST INTERESTING war stories are found far from the battlefield. Writer Susan Ronald has a nose for locating them. In her last book she pulled the curtain back on a mysterious figure at the heart of Nazi art plundering in Europe. She chose an equally intriguing subject for her latest book, A Dangerous Woman: American Beauty, Noted Philanthropist, Nazi Collaborator–The Life of Florence Gould.

It’s a story rich with potential. The beautiful and charming Florence and her wealthy financier husband Frank Jay Gould were bold-faced names of their time, providing grist for gossip columns as the American couple rubbed elbows with Europe’s faded aristocrats at the baccarat tables, night clubs, and decadent balls in prewar France. Frank supplied the money and Florence the social and artistic ambitions.

When the Nazis occupy Paris in 1940, the 45-year-old Florence falls back on her looks, charm, and flexible morals. “Above all else, Florence was determined to survive and to thrive despite the occupation, just as she had done her entire life,” Ronald writes. “If that meant joining the legions of women who chose la collaboration horizontale—bedding Germans for a better life—then so be it. And bed them she did.”

Gould cultivated top Nazi officials, including Helmut Knochen, commander of the SS Security Service in occupied Paris, and Carl Ludwig Vogel, who controlled Nazi-run black markets in the city. She had her hand in prostitution rings serving Nazi officers, boosted her art collection with works seized from Jews, and regularly flaunted the everyday food and other restrictions most Parisians endured, Ronald alleges. While much of the city was practically starving, Gould was still entertaining lavishly.

What almost became her undoing was her involvement in a complex banking scandal centered on efforts to hide Nazi wealth as the Allies were closing in. After the war, her actions would come under scrutiny, but the level of her culpability was questionable. There was also evidence that she had helped the Resistance even as she cozied up to Nazis. In the end, the U.S. Justice Department declined to prosecute.

Ronald rightly condemns Gould for her opportunism and greed. She is on shakier ground when arguing that Gould was a dangerous woman who escaped justice. Ronald lays it on thick, describing Florence as “cat-like”; a “femme fatale”; “man-eater”; “steamy enchantress”; and “lioness.”

The author doesn’t shy away from taking cheap shots. Consider the description of Florence’s relationship with her “dim but gorgeous waterskiing instructor,” Georges Ducros: “Undoubtedly, the handsome Georges also taught her other tricks and contortions in the boudoir.” It’s also possible their relationship was simply limited to waterskiing.

The author’s apparent disdain for her subject sometimes detracts from the narrative. Florence Gould was driven by conflicting motives. She was drawn to art and literature even as she made choices based on greed and hedonism. There’s no need to turn it into a morality tale: it’s the ambiguity that makes a story like this compelling. —Jim Michaels is a former war reporter at USA Today and the author of A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq’s Deadliest City and Turned the Tide of War (2010).