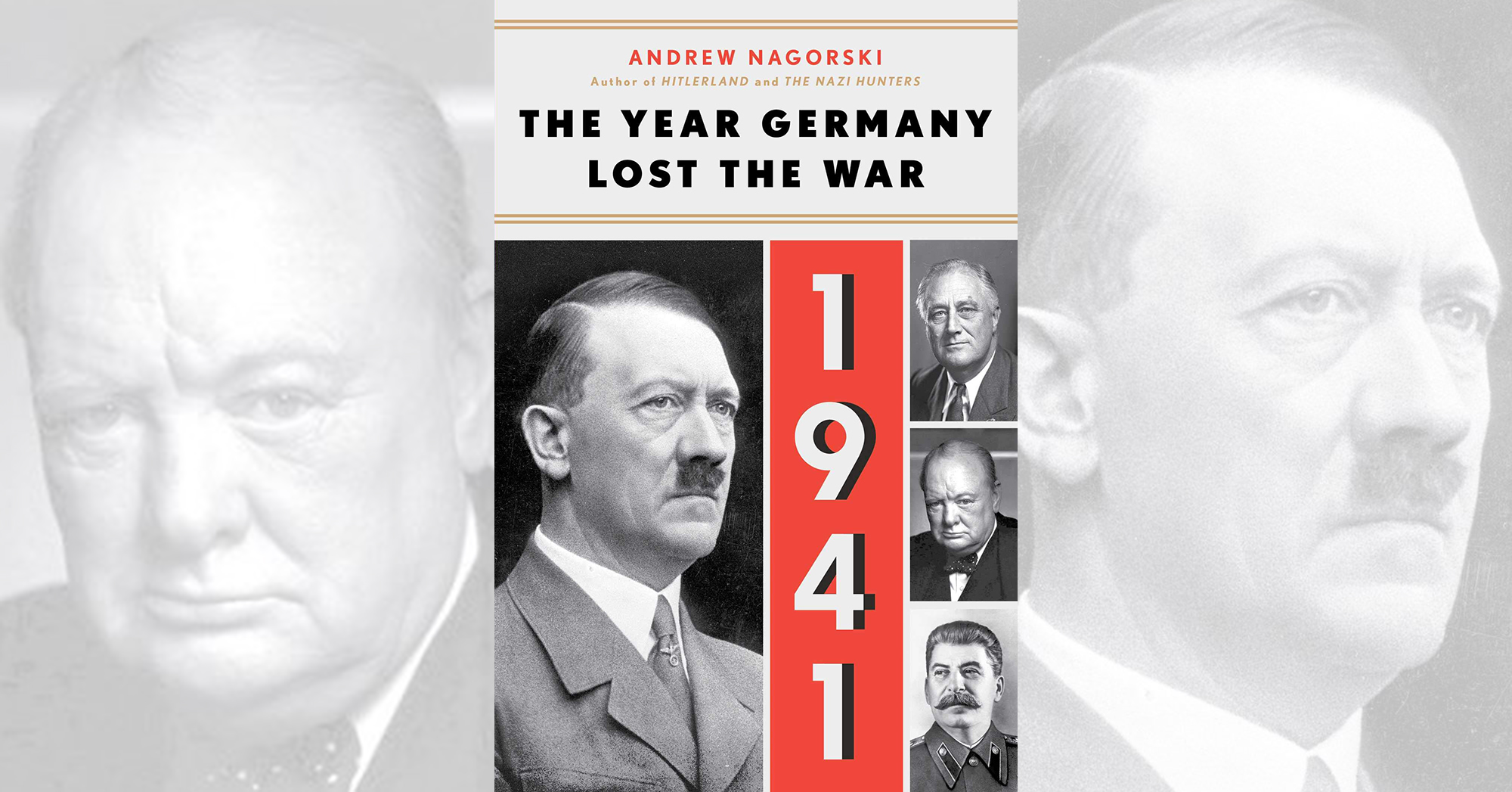

1941: The Year Germany Lost the War, by Andrew Nagorski, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2019, $30

On Dec. 30, 1941, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill addressed the Canadian Parliament. Fresh from consultations with President Franklin Roosevelt, he presented a bold vision for the future course of the war. The boldness was not new, but there was a new assurance the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt. From the beginning of the war Churchill had spoken of Britain fighting on alone, whatever the cost. That day he spoke eloquently of a circle of avenging nations assaulting the citadels of the guilty powers.

Best-selling historian and award-winning journalist Andrew Nagorski focuses on 1941 as the year that set the trajectory leading to Nazi Germany’s ultimate defeat by the Allies. By year’s end Adolf Hitler had made almost every wrong decision possible—both political and military—thereby ensuring the destruction of the Third Reich.

Hitler was a gambler, and in 1940 he consistently won; but in 1941 his gambles on escalation proved disastrous. Frustrated by Britain’s refusal to capitulate, he invaded the Soviet Union that June, gambling on swift victory. But a series of military blunders and his willful blindness to a reality that didn’t conform to his expectations would turn the operation very sour indeed. When Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, Hitler rushed to declare war on the United States—believing, incredibly, as Nagorski brings out, that this widening of the war was to Germany’s advantage. The war became a global conflict. Instead of confronting a bombed and beleaguered Britain standing alone, Hitler had made two powerful new enemies—the Soviet Union and the United States.

Nagorski skillfully weaves diplomatic, political and military narratives into a compelling whole. Richly contextualized, his telling of this crucial year is set in a broad framework of the conflict from its beginnings forward into the postwar world. His treatments of the personalities and thoughts of Churchill, Hitler and Joseph Stalin as they made decisions (good and bad) flowing from their purposes add much to the book’s engaging character.

—Justin D. Lyons