On the afternoon of Thursday, September 9, 1943, Adm. Carlo Bergamini was a worried man. The day before, the Italian government had signed an armistice, and that morning, at 2:30 a.m., he had sortied from La Spezia to deliver the remains of Mussolini’s once-proud fleet to the Allies at Malta, as required by the armistice terms. Even as his ships left harbor—the battleships Roma, Italia, and Vittorio Veneto, accompanied by three cruisers and an escort of eight destroyers—the first American troops were storming ashore at Salerno in the face of what would soon be ferocious German resistance. Hitler’s military was not about to accept Bergamini’s move without a fight, either; indeed, the ships had departed just ahead of German soldiers seizing the port.

Roma, his flagship, was just over a year old, a graceful ship of over 45,000 tons displacement, armed with nine fifteen-inch cannon in three triple-mount turrets, capable of making nearly 32 knots. Even so, Bergamini was under no illusions as to its vulnerability. Air attacks had already savaged Italy’s fleet, most notably in the British strike at Taranto in 1941. Bergamini’s fleet was far from the reach of friendly air cover, operating in waters that the Luftwaffe considered its own, and facing the risk of aerial attackers moving ten times as fast as they.

As dawn rose, he sailed west of Corsica, and then turned south, hugging its coast, joined by three more cruisers and two destroyers that had left Genoa. Allied reconnaissance aircraft reported his movements, and British and American naval authorities noted with approval that the Italian fleet was complying with the instructions they had given.

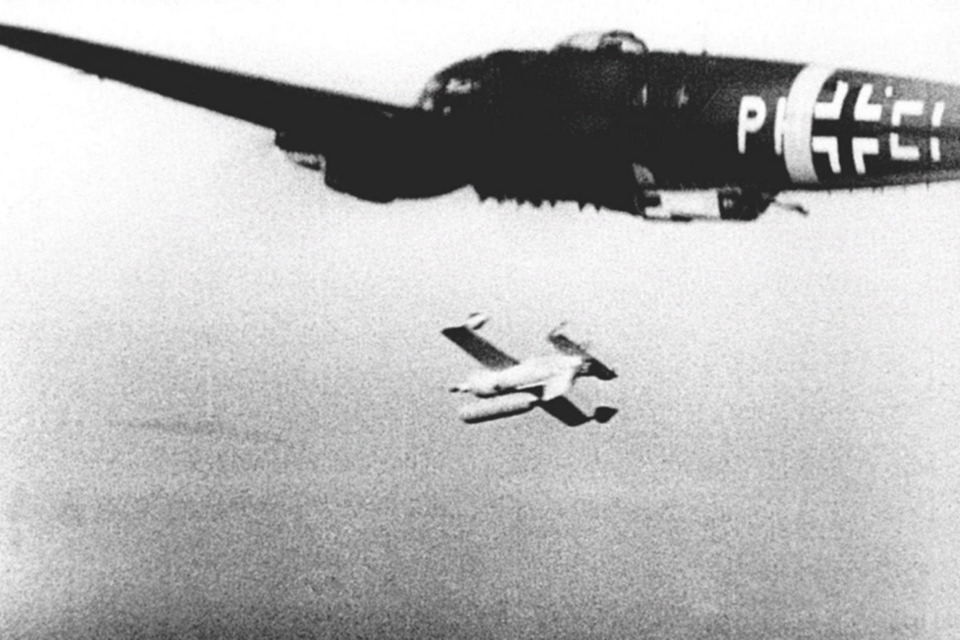

At approximately 3:50 p.m., a formation of five twin-engine airplanes passed high overhead. Lookouts at first likely thought them Allied aircraft, but instead they were Dornier Do 217K bombers from the Luftwaffe’s III Gruppe of Kampfgeschwader 100. A second formation of six aircraft followed close behind. Based at Istres, France, and commanded by Maj. Bernhard Jope, a legendary ship buster, III/KG100 was one of the Luftwaffe’s most notorious antishipping bomb wings.

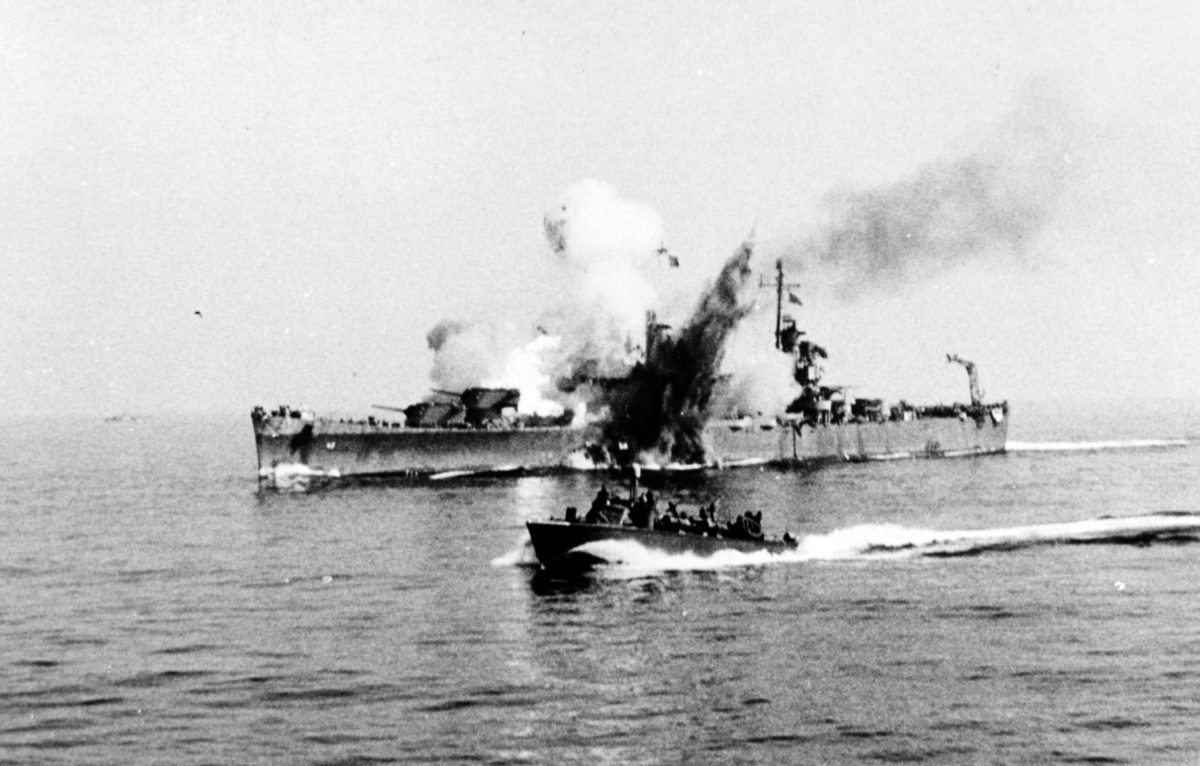

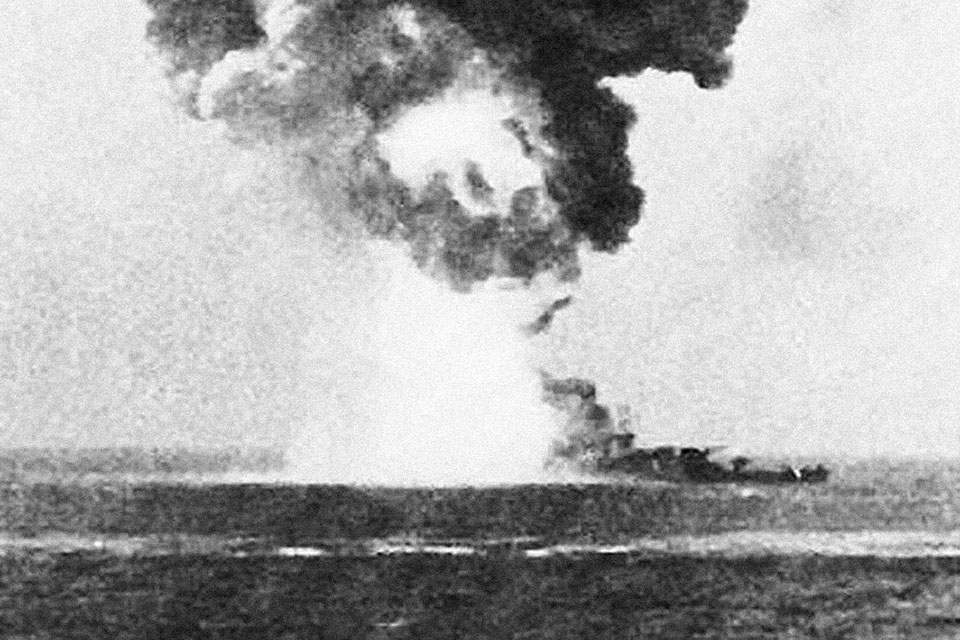

As the intent of the airplanes became clear, the ships began evasive maneuvering, causing the bombs from the first group to fall harmlessly into the sea. The second group, however, struck with unerring accuracy. Italia took a bomb hit that damaged its steering and temporarily left it out of control. But it was the flagship that the Luftwaffe pounded with particular effect. As Roma turned, one bomb struck its bridge, the detonation instantly killing Bergamini and his staff. A second bomb followed, slicing through the deck between B turret and the shattered bridge, burying itself deep in the ship before exploding. B turret was torn from its mounts, the ship’s hull opened to the sea, and a raging fire broke out. Listing and burning, Roma drifted out of control, as its crew desperately tried to save their ship. Twenty minutes after the attack, the forward magazine erupted in a thunderous blast, tearing the ship asunder. Its broken halves swiftly sank, carrying with them over 1,350 of Roma’s crew.

Bergamini’s flagship had been destroyed by a PC1400X, a guided bomb known more familiarly as the Fritz X. It anticipated by a quarter century the smart bombs that are now commonplace in the air arsenals of many nations. Basically a conventional PC1400 bomb equipped with a guidance package, four fins to give it some gliding ability, and a twelve-sided box kite–like tail unit for stability and control, Fritz X was a lethal ship killer. A Do 217K medium bomber could carry two of them, one under each wing, hanging from pylons between its engines and fuselage. The Dornier approached and bombed its target as if on a conventional bombing run. But then its pilot throttled back, so that the plane would not overrun the falling bomb. The descending Fritz X displayed a bright flare, which the Dornier’s bombardier used as a reference point, manipulating a small joystick to send radio pulses to the bomb’s tail surfaces, controlling its descent path until the flare merged with the target.

In 1938, German airmen were fighting over Spain, already finding it difficult to attack small targets with precision. Max Kramer, an engineer at Berlin’s Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (German Aviation Research Institute) began experiments using control surfaces to alter the path of a falling bomb. Although he began with small weapons, the German Air Ministry recommended he work with the heavyweight PC1400. By the end of 1939, Kramer and a three-person team had evolved the Fritz X, dropping their first example in June 1940. Extensive testing in laboratories at Göttingen University, Aachen Polytechnic, and Telefunken, followed by a series of drop tests over a specially instrumented bombing range at Peenemünde, refined its aerodynamics, guidance, and performance. In a final series of drop tests in early 1942, crews launched the experimental bombs from 20,000 feet. For the time, the results were extraordinary: 50 percent fell within 23 feet of the aim point, and 100 percent within 48 feet. Later that year, Rheinmetall-Borsig put Fritz X in full production.

In the summer of 1941, British intelligence had obtained glimmerings of Germany’s guided bomb experiments from POW revelations and information sent by agents. The reports raised little alarm; such efforts had a long and largely unproductive history. As early as 1918 the Siemens-Schuckert company had developed a gliding torpedo for possible use from Zeppelins and large bombers, making a number of disappointing test drops. At the same time, British and American developers had tested their own experimental gyro-stabilized “aerial torpedoes”—drone airplanes—and in the late 1930s, both countries had developed radio-controlled flying targets: more promising, but still far from practicable for a weapon.

Even after Enigma intelligence revealed in late July 1943 that fifty specially modified Dornier Do 217s equipped to carry two such weapons were being sent to Istres, Allied commanders still evinced little interest. Only in August of 1943 would they awake to any potential danger, and even then they failed to realize the truly punishing trial they were about to experience.

The devastating attacks began the final week of August, with Dorniers from III/KG100 targeting antisubmarine vessels patrolling the Bay of Biscay. On August 25, they near-missed HMS Landguard and HMS Bideford, killing one sailor. On August 27, Egret, a small Royal Navy sloop, took a direct hit and went down, with the death of 194 sailors.

The sinking of Roma on September 9 heralded the start of a sharply more dangerous phase. Just two days later, U.S. Army general Mark W. Clark stood on the bridge of his command ship, Ancon, watching the approach of the light cruiser Savannah. The ships were off Salerno, supporting the Allied landings on the Italian mainland. Suddenly Clark heard “a terrific screeching noise” that “seemed to be heading directly toward the Ancon.” But, instead, a Fritz X plunged into the cruiser’s No. 3 turret, exploding deep within the ship.“Instantly, all was chaos, smoke, blood, and death,” as a navy report later described the scene. The blast ripped open the hull and seawater flooded in. The forecastle was awash within minutes and the ship seemed almost certain to go down. Nearly two hundred sailors were killed in the blast and fire, with most of the gun crews asphyxiated in their turrets by smoke and fumes. The blast knocked out all the ship’s boiler fires, leaving it without power. Heroically, and against all odds, the crew managed to right the seriously listing vessel and get the boilers relit, and Savannah was able to limp into Malta. Four crew members trapped in the radio room were freed only when workers in Malta, sixty hours later, drilled and chipped their way through the steel deck to reach them.

Over the next five days, four more ships were hit off Salerno: A Fritz X crippled the British cruiser Uganda on September 13; tugs towed it to Malta. The next day, a guided bomb sank a tanker, Bushrod Washington. On the fifteenth, another so badly damaged SS James Marshall as to render it only fit for service as part of an artificial harbor constructed for the Normandy invasion. Then, on September 16, the British battleship Warspite took three Fritz X hits, one a near-lethal hit in a boiler room, briefly robbing the tough old Jutland veteran of all power and causing extensive flooding. Very badly battered, it, too, joined the growing fleet of damaged ships undergoing repairs in Malta.

Allied experts soon discovered that several of the attacks— including those on Egret and Bideford—had been carried out with a second, and even more sophisticated, radio-controlled weapon. The Hs 293 was actually more airplane than bomb, befitting the background of its creator, Herbert Wagner. A former marine engineer who became one of the most distinguished figures in German aeronautics, Wagner had pioneered the design of lightweight all-metal structures, designed an early jet engine for Junkers, and then, at the invitation of the air ministry, joined the Henschel company at Berlin-Schönefeld to assist in their weapon development.

The Hs 293, which had its first test flight in 1940, amply reflected his expertise. Equipped with a rocket booster and weighing just half as much as the Fritz X, it was a true pilotless aircraft. Launched from the twin-engine Do 217E and, later, the four-engine He 177A, it had nearly three times the range of the Fritz X. The attacking bomber could launch it as much as five miles from the target, safely out of range of shipboard antiaircraft guns. What was more, the bomber could pass three-quarters of a mile to one side of the ship, rather than straight toward it. After launch, the missile fell away, and its engine and a flare ignited. The engine burned for approximately twelve seconds, producing a thrust of 1,500 pounds, accelerating the bomb and boosting its range. As with the Fritz X, the bombardier tracked its progress by following the tail flare and radioed steering commands via a joystick.

In the face of the unremitting assault, Allied scientists scrambled to devise ways to foil the bombs. Ideas included pointing searchlights at the attacking bomber to momentarily blind the bombardier or firing flares to mimic the glide bomb’s guidance flare. More conventional tactics were also proposed, including smoke screens, evasive maneuvering, intensive antiaircraft barrages, and constant fighter patrols.

The most promising new idea was to jam the radio guidance link between bomber and bomb. The catch was that scientists needed an intact bomb, so they could take apart the radio gear and figure out the frequency it operated on, as well as the method used to encode the steering instructions within the radio signal. Technical intelligence personnel from Britain’s Air Ministry pored over bomb fragments for vital clues, their job made harder by the Germans’ practice of equipping the bombs with small self-destruct charges that would blow up the guidance unit even if the bomb itself failed to detonate on impact.

Finally, in October, British scientists discovered nine Dorniers abandoned at Foggia: seven Fritz X–launching Do 217Ks and two Hs 293–launching Do 217Es. These contained sufficient portions of Telefunken FuG 203 Kehl transceivers and their aerials, control panels, and bomb launch mechanisms, to permit technical analysis.

They could not, however, put this find to practical use fast enough to prevent serious losses throughout November. On the thirteenth of the month, a bomb struck HMS Dulverton off Kos, forcing the destroyer’s scuttling. On the twenty-first, twenty-five He 177As from the II Gruppe of KG40 (an antishipping bomb wing based at Bordeaux–Mérignac) attacked a convoy off Spain. Thanks to adroit ship handling, the Luftwaffe’s own blundering assault, and the actions of an RAF Liberator crew, which repeatedly attacked the wheeling bombers, only two of the forty-six bombs that were launched hit; still, they damaged one vessel and sank another, SS Marsa. On the twenty-sixth, during another He 177 attack on a Suez-bound convoy off the Algerian coast, intercepting fighters shot down six of the bombers. However, at least one bomber managed to score, and with terrible effect. An Hs 293 hit the Rohna, a converted British troopship, starting raging fires. Nearly twelve hundred men perished on the blazing ship or in the water, including more than a thousand American GIs— a shocking loss whose details were kept secret for many years after the end of the war.

Countermeasures were still not fully effective when, on January 22, 1944, British and American forces commenced Operation Shingle, the landing at Anzio–Nettuno. An Hs 293 dropped at dusk damaged the British destroyer Jervis on January 23. Fear of more such attacks prompted the Allied naval commander, Rear Adm. Frank J. Lowry, to order his cruisers and destroyers out to sea every afternoon, even though this meant abandoning nighttime fire support missions for troops already fighting ashore.

Even with this precaution, on the twenty-ninth, guided bombs hit the British cruiser Spartan, capsizing it, and set the American transport Samuel Huntington ablaze; it blew up the next morning. In response, Adm. Sir John Cunningham ordered that the large cruisers be sent to the roadstead only if troops ashore were facing extreme threats. The many lightly armored destroyers, transports, and landing craft plying waters off the beachhead would have to continue to take their chances. Consequently, on February 16, the SS Elihu Yale took a bomb hit that sank it and a landing craft moored alongside, and on the twenty-fifth, the British destroyer Inglefield sank under another missile attack.

Fortunately, with these assaults, the high-water mark of German antiship missile warfare had passed. Over the next few months, the Allies introduced electronic jamming countermeasures to limit the effectiveness of the Fritz X and Hs 293; of greater significance, Allied fighter patrols and antiaircraft fire increasingly made operations near naval forces even riskier than they had been. Only occasional successes attended subsequent German use of precision bombs against shipping. At Normandy in 1944, an unjammed glide bomb attack on the night of June 6 destroyed one LST, and in the early hours of June 8, another undetected glide bomb so damaged the American destroyer Meredith that it had to be abandoned.

After the landings in Southern France and Normandy, German antishipping operations of all kinds declined dramatically. In the meantime, German scientists and engineers attempted to build on the success they had achieved with the Fritz X and, particularly, the Hs 293. They explored wire and television guidance to overcome the effects of jamming and created new and potentially even more devastating designs, including the Mistel program, an effort to modify war-weary Ju 88 bombers into remote-controlled flying bombs carrying a 7,700-pound shaped-charge warhead.

Such work complemented the Nazi regime’s heavy investment in futuristic weapons such as jet fighters, long-range rockets, pilotless cruise missiles, and air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles. But most of these efforts proved woefully fanciful, technological dead ends, or were impossible to achieve before the Hitler regime’s collapse. Thus, Nazi precision weapons, far from constituting war-winning strategic wunderwaffen, furnished at best temporary tactical hindrances to the Allies’ inexorable drive to Berlin.

Yet the Nazis’ smart weapons offered a glimpse of the future: one the Allies, particularly the United States, would over time embrace. The loss of the Roma in particular greatly accelerated official interest in several American research programs that had been under way since the beginning of the war but had yet to yield practical results.

One was the navy’s TDR, which would become the antecedent of the modern cruise missile. The TDR owed its origins to a fortunate partnership between Commodore Oscar Smith, a visionary surface officer; Lt. Comdr. Delmar Fahrney, a flying bomb enthusiast; and television pioneer Vladimir Zworykin, a Russian émigré and RCA’s chief scientist. In 1942, the three men successfully demonstrated controlling a drone aircraft while it approached and then dropped a dummy torpedo against a maneuvering destroyer. The results so impressed Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King that he authorized development of an assault unit flying a specially built attack drone.

The TDR was built by a small firm, the Interstate Aircraft Company, assisted by the Wurlitzer organ company and a furniture manufacturer. Controlled from an accompanying Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bomber whose operator “saw” through the TV eye of the drone, the TDR could carry a 2,000-pound bomb. Deployed to the Solomons, TDR drones saw a month of combat testing. Their first sorties took place on September 27, 1944, when four were launched by Special Air Task Group 1 from Stirling Island against a Japanese merchant ship used as an antiaircraft trap off South Bougainville. Two destroyed it. Trials ended in late October, by which time the group had launched 46, of which 21 successfully hit their targets. (That success dramatically contrasted with conventional bombing. When 47 B-29s raided Yawata, Japan, in the summer of 1944, only 1 of their 376 bombs actually hit the target. It took 108 B-17s dropping 648 bombs to guarantee a 96 percent chance of getting just two hits on a Nazi power plant.)

The U.S. Navy also developed a self-guided bomb, the Bat, which used built-in radar to home in on an enemy target. When deployed in the last few months of the war, it sank a destroyer and several freighters. Moreover, during the last year of the war, the air force produced a third American guided bomb, Azon. Like the Fritz X, it was steered over a radio link by a bombardier, who followed the bomb’s fall visually with the aid of a flare. By war’s end, over 15,000 had been produced by Gulf Research and Development Company. Early trials in Europe met with indifferent success, but by December 1944, Azon had been refined to a point of deadly efficiency. In Burma, the 7th Bomb Group used it with extraordinary effect against bridges. On December 27, six B-24s of the 493rd Bomb Squadron dropped eighteen Azons, which destroyed a 300-foot steel bridge at Pyinmana that had withstood scores of attacks. Altogether, twenty-seven Japanese bridges fell at a cost of 450 Azons.

TDR, Bat, and Azon were the apex of American smart air weapons in the Second World War, but already developers were looking well beyond, envisioning supersonic and hypersonic global-reaching cruise-and-ballistic missiles, heat-seeking bombs and missiles, and robot aircraft. Out of the spoils of Nazi Germany’s technology came even more ambitious projects. Nonetheless, official interest in precision guidance all but vanished after the war. For much of the next two decades, unguided “dumb” bombs continued to dominate America’s weapons inventory, and military commanders saw little reason to change that. The advent of the atomic bomb added its own limits on military thinking; planners saw conventional war as outdated.

Only when America found itself once again in a major conventional war in Vietnam, and American jets took a painful pounding when attacking difficult and well-defended targets such as bridges, was interest in precision guidance reborn for good—with the legacy that the world witnessed so vividly in the air war over Serbia and the two wars in Iraq.

Originally published in the September 2007 issue of World War II Magazine. To subscribe, click here.