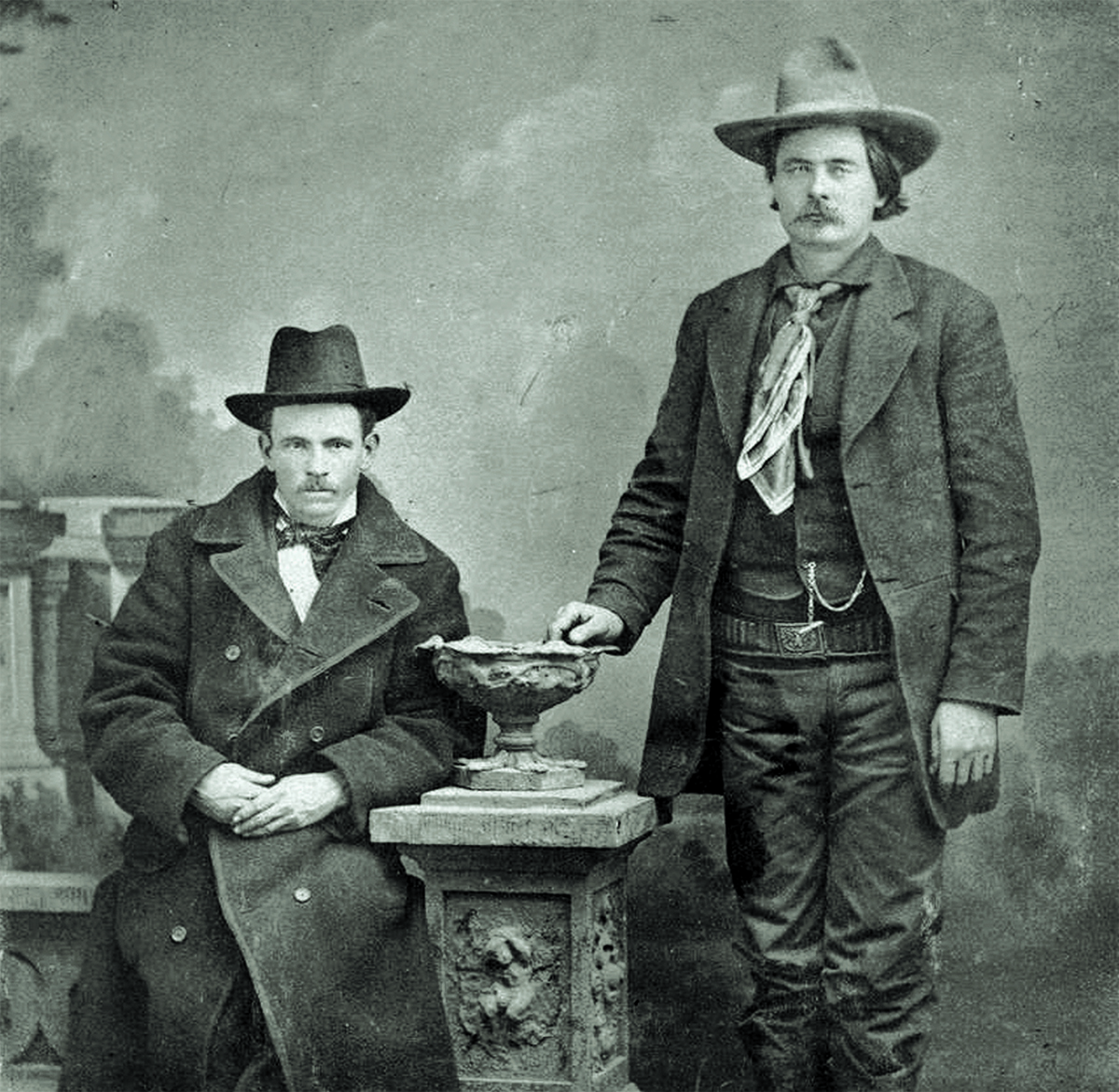

Bob Olinger is the bully we all love to hate. A favorite recurring scene in big-screen Hollywood Westerns depicts the contemptible deputy getting his just desserts from the muzzle of a shotgun wielded by Billy the Kid in Lincoln, New Mexico Territory, in 1881.

Such depictions invariably focus on the lawman’s personality flaws. It’s worth noting, however, he had managed to win the undying love of one Lily Casey, to whom he was reportedly engaged at the time of his murder. An early resident of Lincoln, Casey (married name Lily Klasner) fondly recalled their romance in her posthumously published 1972 memoir My Girlhood Among Outlaws, a veritable trove of information about Lincoln County War figures she knew personally.

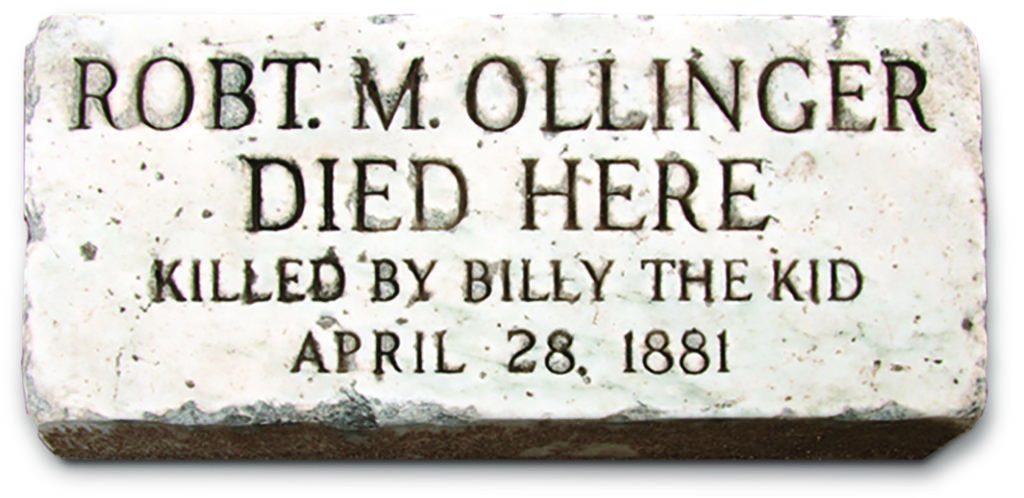

The Kid’s life story had another chapter after he killed Deputies Olinger and James W. Bell while escaping from the Lincoln County Courthouse on April 28, 1881. Not so Olinger. His body was reportedly taken to Fort Stanton and there interred without ceremony. Popular belief, old photos, magazine articles and local legend all suggest he is buried at the back of the old Fort Stanton Cemetery. If there ever was a marker on the slain deputy’s grave, it has long since disappeared.

Who Was Bob Olinger?

Ameredith Robert B. Olinger was probably born in 1850 (other sources say 1841) in Carroll County, Indiana. By 1856 his family had migrated west to Delaware, Polk County, Iowa, moving again in 1858 to Mound City, Linn County, Kansas Territory. After that came moves to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), Texas and, in 1876, New Mexico Territory.

While serving a stint as marshal of the rough-and-tumble Lincoln County town of Seven Rivers, Bob killed two men in gambling disputes on separate occasions. Olinger participated in the 1878 Lincoln County War as a member of the Lawrence Murphy–James Dolan faction. (Billy fought for the opposing faction headed by John Tunstall, Alexander McSween and John Chisum.) Months later, Olinger gunned down one Bob Jones amid a rivalry stemming from another gambling dispute, though county authorities dismissed a murder charge against him in October 1879. That same month Pat Garrett was elected Lincoln County sheriff and appointed Bob one of his deputies.

Olinger’s reputation as a “bully with a badge” mostly stems from his nasty treatment of the Kid while Billy was Garrett’s prisoner in Lincoln. Billy got his revenge that fateful day in April 1881 when he blasted Bob with his own shotgun, killing him instantly. The deputy faded into history, as did the whereabouts of his grave. His end is where my curiosity began.

the marker) fell after the Kid shot the deputy with his own shotgun. (Daniel Mayer, CC BY-Sa 3.0)

Wild, Wild West

What About Bob?

After reading about Olinger’s probable burial location, I went on a hunt in Fort Stanton. Alert to my old enemies, snakes, I examined existing headstones in the old post cemetery. While nothing definitive popped up, two distinctly different graves toward the back of the burial ground stood out. They matched the scant available information, so I thought it would be an easy search. Little did I imagine it would turn into a monthslong investigation.

Along the way I crossed paths with several interesting people. At present-day Fort Stanton Historic Site, managed by the state, I spoke with Ranger Javier Trost about Olinger’s grave. He in turn put me in contact with Kenneth Walter of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, whose knowledge of Fort Stanton history is unmatched. Walter has researched burial records, autopsy records, maps, surveys, patient rolls, soldier deaths, military burial removals, cemetery records and just about everything else on paper about the site and its history. He’s also mapped and photographed almost every inch of the fort and surrounding grounds.

While playing phone tag with Walter, I got a text from Steve Sederwall, a former federal officer and onetime mayor of Capitan, New Mexico, who has long been interested in the Billy the Kid story. (He once tried to prove the Kid had not been killed in Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory, on July 14, 1881.) It turned out Sederwall was also interested in pinpointing Olinger’s grave. Agreeing that any lawman killed in the line of duty deserves a grave marker and should not be forgotten, we arranged to meet with Walter together.

Mapping It Out

To that meeting Walter brought not only books, surveys, letters and reports with burial details but also documents specifying who was buried where in the cemetery. Complicating matters was the fact that in 1896 the Army had moved soldiers’ graves from recently deactivated Fort Stanton to Santa Fe National Cemetery, and records of that reinterment effort are spotty or nonexistent. Sederwall and I had noted widespread disturbance on the grounds of the post cemetery, but had Olinger’s remains also been moved?

According to a map of the old Fort Stanton Cemetery, Olinger rests in Plot No. 69. But period records indicate an Army colonel was buried in that plot until reinterred in Santa Fe. Neighboring Plot No. 71 holds the remains of Murphy-Dolan gunman Charlie “Lallacooler” Crawford, who was shot on July 17, 1878, amid the five-day Battle of Lincoln (the climactic event of the war) and died a week later at the Fort Stanton hospital. But his grave, too, lacks a marker. Other records are contradictory and incomplete, and distances between graves do not match those shown on maps. Most likely the Army did not disturb Bob’s grave, and he remains buried at Fort Stanton. But where if not in Plot No. 69? Walter offered another possibility.

Within a half mile of Fort Stanton are several long-forgotten historic sites Walter has since rediscovered and documented. Among them is a cemetery in use around the time Olinger was buried in spring 1881. Today only scattered stones remain to mark its boundaries. It is a lonesome place, with a beautiful view of the distant Sierra Blanca. Though records are lacking, it’s possible Olinger was instead buried there. If so, his body lies alongside dozens of others in unmarked, untended graves. Trying to find and identify his remains in that ghost cemetery would take far more extensive research and plenty of luck. Perhaps somewhere (in someone’s attic or a storage bin at Fort Stanton) there is a record book, report or survey that lists the internees and their respective locations.

Meanwhile, the mystery of where Bob Olinger lies remains unsolved. No matter where old Bob rests— the old Fort Stanton Cemetery, the abandoned cemetery discovered by Walter or another location — it is undoubtedly an unmarked grave. I hope to one day discover and mark the spot, for no matter his faults, the slain deputy deserves more than his legacy of meanness.