One of the few constants of the Vietnam War—one eagerly anticipated by American troops, that is—was the annual Bob Hope Christmas Show. From 1964 to 1972, Hope included South Vietnam on his annual trips to visit troops during the holiday season, a tradition that started for him during World War II. “Back in 1941, at March Field, California…I still remember fondly that first soldier audience,” Hope once said. “I looked at them, they laughed at me, and it was love at first sight.”

“And did you read where President Johnson just requested another $50 billion to cover the rising cost of the war? Wouldn’t it be awful if we ran out of money and they repossessed the war?”

While only a small fraction of the 2.5 million troops who served in Southeast Asia actually got to attend Hope’s performances, for those who did he managed to break the monotony, ease the loneliness and give the troops in combat zones across Vietnam a couple of hours of laughter—and a memory for a lifetime. Bob Hope’s classic opening monologues of rapid-fire jokes always took jabs at the GIs and the specifics of the local situation.

Under a hot sun or a driving rain, his young audiences laughed and cheered the legendary comedian and his cast of singers, dancers and the musicians of Les Brown and his Band of Renown. Hope’s shtick included a constant, sometimes bawdy banter with the other performers, taking plenty of shots at the absurdities of military life while conveying a real sense of how difficult it was for the troops to be away from home during the holidays.

Hope began taking his show on the road after the United States entered World War II and the United Service Organization (USO) started sending Hollywood and radio entertainers to perform for military audiences at bases in North Africa, Europe and the South Pacific. Already a giant movie and radio star, Hope traveled overseas six times, logging more than a million miles during World War II. At the outset of the Cold War in 1948, when the Soviets closed all ground travel from West Germany to Berlin, Hope’s show followed the reserves sent by President Harry Truman to facilitate the airlift into the western sectors of Berlin. Later, Hope traveled to Korea in the early 1950s after North Korean troops invaded South Korea, and all during the 1950s his show played at military bases in Japan. By the 1960s, Hope’s Christmas shows for troops overseas had become a fixture of America’s traditional holiday season.

At Bien Hoa Air Base on Christmas Eve:

“I asked McNamara if we could come and he said, ‘Why not, we’ve tried everything else!’ ”

As early as 1962, Hope wanted to go to Vietnam to perform for the growing contingent of American military advisers. Although planning moved at a steady pace for a 1963 show, the Pentagon ultimately pulled the plug on it because of what it considered too high a risk. Nevertheless, at age 61, Hope persisted and won approval for his first Vietnam shows in December 1964. With his new destination came a new twist to the shows: They would be filmed to be broadcast as holiday specials in early January of the next year.

These filmed productions required a new level of effort in organization and execution to bring them to a new domestic audience. Hope remained the star and the driving force behind his tours. Other leading performers such as Connie Stevens, Ann-Margret and Joey Heatherton welcomed the opportunity to join him, despite the stress of travel into a far-flung war zone and the hardships they encountered there. Hope’s Vietnam engagements were among the most dangerous ever for the funnyman and his entertainers.

On December 15, 1964, Hope’s contingent left Los Angeles aboard a military transport aircraft large enough to carry the support staff and all the entertainers, including Les Brown and his band, the reigning Miss World, Anita Bryant, actresses Janis Paige and Jill St. John and comic actor Jerry Colonna, who had been part of Hope’s group during World War II.

The tour covered 25,000 miles and included stops at Wake Island and Guam. They flew on to Korea for a performance in which Hope opened his monologue by labeling South Korea as “Vietnam North.” He won thunderous applause when he cracked, “We had a little trouble landing in Seoul: Someone stole the runway.”

Security was exceptionally tight for Bob Hope’s first visit to Vietnam. Although the planners had made intricate arrangements through the offices of Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) prior to his December 24 landing, there had been no official announcements or confirmation of Hope’s visit. And the locations of all his shows remained secret. Even Hope and his staff never knew the name of the base they were to perform at until they landed. Reporters noted that plans for Hope’s visits to different areas were more secret than those for generals or Cabinet officials. Troops who made up the audiences were never told who would be visiting until the last minute.

Hope and his entourage were given stern warnings from MACV. While some were routine for any overseas travel—avoid all water and ice because none was safe to drink, and stay away from all milk products—the threats related to terrorism were especially serious. They were told to stay away from windows in restaurants and in their hotel rooms, and to keep their drapes closed. And a final caution: Drop to the floor when they heard an explosion. In spite of the dangers, the shows went on, but the sound of aircraft overhead during a performance always brought a startled look from Hope.

The first show in Vietnam, on Christmas Eve, began almost immediately upon landing at Bien Hoa air base, which the Viet Cong had bombed in November, destroying many aircraft. As soon as Hope reached the stage, he opened with a hearty “Hello, advisers! I asked Secretary McNamara if we could come and he said, ‘Why not, we’ve tried everything else!’ No, really, we’re thrilled to be here in Sniper Valley. What a welcome I got at the airport…they thought I was a replacement.”

The first show in Vietnam, on Christmas Eve, began almost immediately upon landing at Bien Hoa air base, which the Viet Cong had bombed in November, destroying many aircraft. As soon as Hope reached the stage, he opened with a hearty “Hello, advisers! I asked Secretary McNamara if we could come and he said, ‘Why not, we’ve tried everything else!’ No, really, we’re thrilled to be here in Sniper Valley. What a welcome I got at the airport…they thought I was a replacement.”

Although a Communist attack was a real possibility, Hope appeared relaxed, swinging a golf club, which became a constant prop during his monologues. “I love the runway you have here,” he quipped. “Great golfing country…even the runway has 18 holes.”

After the show, the group moved to Saigon, where the dire warnings of danger literally exploded into reality. Hope and most of the performers stayed at the Caravelle Hotel, while Brown and members of the band stayed at the Continental Palace. Both were close to the Brinks Hotel, which served as a bachelor officers quarters for the Americans. That afternoon, a bomb flattened the Brinks, sent glass and other debris into some rooms of the Continental and shook the Caravelle. No one in the troupe was injured, but the explosion left all the hotels without water or electricity. True to form, Hope stitched this incident into his act at Tan Son Nhut the next day: “I want to thank General Westmoreland for that wonderful welcome yesterday. We opened with a bang!” And at the small outpost in the Mekong Delta, he joked: “A funny thing happened to me when I was driving through downtown Saigon to my hotel last night. We met a hotel going the other way.”

Next up was a flight to Pleiku, a small helicopter base in the highlands near the border with North Vietnam, with heavy security in place for the visitors. Rumors had circulated that Hope’s group was headed their way, but no one was sure until the airplane landed and Bob Hope walked onto the stage. “What a welcome,” he declared. “Wherever we land we’re met by thousands of cheering servicemen…they think it’s Secretary McNamara with shut-down orders!”

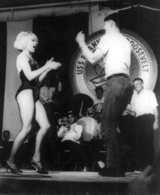

Jill St. John did her stand-up routine with Hope, trading one-liners about her IQ and his golf score, and later in the show she performed the segment that became very popular with the servicemen, when they joined her on stage to dance the “Go-Go” to the beat of Les Brown’s band.

At Da Nang, the tour’s largest audience in Vietnam, Hope made light of the frequent changes in government that year: “Vietnam is a very democratic country, everyone gets to be president.” As usual, he joked about military cutbacks and the aircraft he was forced to fly in: “It’s one of the earlier jets…instead of afterburners, it has an oven and a bag of charcoal.”

The last show on the 1964 Vietnam tour was at the seaside city of Nha Trang. At this and every performance, after a brief prayer from the chaplain, Anita Bryant closed the show by singing the first verse of “Silent Night,” and asked the troops and other performers to join in on the second verse, a tradition that continued through all the show’s years. The group left Vietnam on December 28 and flew to Clark Air Base in the Philippines for a show before heading home. Arriving back in Los Angeles on December 30, Hope told reporters, “This was the most exciting Christmas trip since 1943.”

1964 NBC Broadcast:

“Let’s face it… we’re the Big Daddy of this world”

The 1964 trip set the pace and the pattern for all of Bob Hope’s visits to American troops around the world for the next eight years. While the performers changed and the locations varied, Hope was always the star and began the shows by strutting on stage with his golf club in hand, firing off jokes tailored to each base. He always had the reigning Miss World and always tried to bring the troops the outstanding glamour star from back home. He started appearing onstage in military uniform shirts and jackets outlandishly decorated with patches, stripes, stars and insignias. And as the number of military personnel stationed in Vietnam grew each year, the tour’s length expanded too.

All the shows were filmed live and later edited down to 90-minute television specials broadcast on NBC in January, sponsored by Chrysler and run commercial-free. The telecasts featured not only the entertainers, but also plenty of shots of the U.S. troops, including footage of the Christmas meals they shared together, and Hope’s visits to the hospitals and hospital ships. At the end of the 1964 telecast, Hope displayed his more serious side:

All the shows were filmed live and later edited down to 90-minute television specials broadcast on NBC in January, sponsored by Chrysler and run commercial-free. The telecasts featured not only the entertainers, but also plenty of shots of the U.S. troops, including footage of the Christmas meals they shared together, and Hope’s visits to the hospitals and hospital ships. At the end of the 1964 telecast, Hope displayed his more serious side:

“We want to thank Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara for making this Christmas trip possible….Let’s face it, we’re the Big Daddy of this world….I talked to a lot of our fighting men over here and even though they’re putting up a great fight, against tremendous odds in this hide-and-seek war, they’re not about to give up, because they know if they walk out of this bamboo obstacle course, it would be like saying to the commies, ‘come and get it.’ That’s why they’re laying their lives on the line everyday….And they said thank you….I don’t think any of us ever had a better Christmas present.”

For the 1965 tour, Hope’s troupe flew for 22 hours in a C-141 and spent much of the flight in rehearsal. Stopping at Guam to refuel, the cast put on a full 2½ hour show.

The American escalation had a direct influence on Hope’s shows. Within a year, the number of American military bases had multiplied, troop levels increased eight-fold, to 180,000, and so had the size of Hope’s audiences. Two fighter escorts accompanied the entertainers to Tan Son Nhut on Christmas Eve, and the cast was rushed to the site of the show. Hope took the stage and announced to the crowd of 12,000 that he had to “come to Vietnam to see his congressman,” referring to the flood of members of Congress who made frequent jaunts to Vietnam at the time.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The troupe flew next to Cam Ranh Bay, where Hope, sauntering across the stage wagging his golf club, scolded the troops: “I don’t know what you guys did to get here, but let that be a lesson to you!” Baking in the hot sun, the troops roared in agreement.

Hope looked relaxed and genuinely enthusiastic—even in the withering heat—when he delivered his monologue at Bien Hoa for the 173rd Airborne Brigade on Christmas Day. His guest star Carroll Baker, hot off the movie Harlow, bantered with him and Colonna, Kaye Stevens sang for the troops and Joey Heatherton danced the “Watusi” with servicemen who were brave enough to step up to the stage.

Hope looked relaxed and genuinely enthusiastic—even in the withering heat—when he delivered his monologue at Bien Hoa for the 173rd Airborne Brigade on Christmas Day. His guest star Carroll Baker, hot off the movie Harlow, bantered with him and Colonna, Kaye Stevens sang for the troops and Joey Heatherton danced the “Watusi” with servicemen who were brave enough to step up to the stage.

On their flight north to entertain the Marines at Chu Lai, Hope’s plane lost an engine on the way, and they arrived late. Hope then set the mood, opening with: “Other bases here in South Vietnam invited me; this one dared me!” Later, at Da Nang, the monsoons caught up with them, and they performed through a heavy downpour. It was here that Hope had some serious reflections on what he was seeing among the troops he was meeting. After the show, Hope told an interviewer: “The kids here seem more optimistic than those at home. They have more confidence in our leaders.”

Bob Hope performed 22 shows and visited five hospitals in 1965. Each show lasted more than two hours, and typically there were two performances a day. Every tour he made to South Vietnam drew the attention not only of American fighting forces, but of the enemy as well. It was not unusual for the Communists to fire on or attack a base shortly after the show ended. After each show at Pleiku in the Central Highlands, the Viet Cong would shell the area.

Christmas Tour 1966:

“The country is behind you 50 percent”

In 1966, for the first time in many years, Bob Hope’s partner and friend since the tours in WWII, Jerry Colonna, was unable to join the troupe after suffering a stroke. Nevertheless, Hope’s company, featuring guest stars Phyllis Diller and Heatherton, left Los Angeles on December 16, and by Christmas they were at Cu Chi. Actress Chris Noel, who was asked by Hope to join the show for this performance, arrived on a chopper in time to join him and the troops for a traditional turkey dinner in the mess. Noticing some men precariously perched on tall poles before the show began, Hope asked during his opening monologue, “How did you get up there? LSD?”

The tenor of the Christmas tour of 1966 reflected changing attitudes in the United States regarding the course of the war, and Hope’s humor didn’t shy away from it. He reassured the troops that “the country is behind you 50 percent.” He then added, “I’m very happy to be here; I’m leaving tomorrow!”

While Hope largely kept his personal opinions out of his on-stage performances, he spoke freely with reporters off stage. At one stop, he announced he was definitely “hawkish” and expressed his desire that the “United States would move a little faster to end the war.”

By Christmas 1967, the number of American military in South Vietnam had reached almost 500,000, resulting in ever-larger audiences and making Hope’s appearances even more important for boosting morale. Joined on the tour by actresses Raquel Welch and Barbara McNair, Hope performed for 25,000 men and women at Long Binh who sat in a brutal sun while organizers fretted about security. He told the troops at Da Nang that Dow Chemical just got even with student protesters: “They came up with an asbestos draft card.” During a visit with the wounded, Hope asked one soldier, “Did you see the show or were you already sick?”

The next year, as audiences swelled, Hope added former Los Angeles Rams player turned actor Rosie Grier to his entourage, and Ann-Margret, who was a hit in her minidress and go-go boots. At Cu Chi, they had to travel in a safety pod of three aircraft to get in, and Hope noted, “Every time we come here, there is action!”

At Cam Ranh Bay, where it poured rain, the ensemble donned hats and remained on stage. “We’re not going to let this little rain shower bother us are we?” asked Hope. “Where’s Billy Graham when you need him?” When a stagehand came to take Ann-Margret’s fur out of the rain, Hope remarked, “Look at this…nothing gets saved but Ann-Margret’s fur.” They finished the show with “Silent Night,” and the audience sat there in the rain and sang with them. “It was the only Christmas they had, and they weren’t going to miss it,” said Hope during the telecast.

At Cam Ranh Bay, where it poured rain, the ensemble donned hats and remained on stage. “We’re not going to let this little rain shower bother us are we?” asked Hope. “Where’s Billy Graham when you need him?” When a stagehand came to take Ann-Margret’s fur out of the rain, Hope remarked, “Look at this…nothing gets saved but Ann-Margret’s fur.” They finished the show with “Silent Night,” and the audience sat there in the rain and sang with them. “It was the only Christmas they had, and they weren’t going to miss it,” said Hope during the telecast.

The 1969 tour left Los Angeles and stopped off in Washington for a state dinner with President Richard Nixon and a rehearsal at the White House, where Hope and guest stars Connie Stevens, The Golddiggers from The Dean Martin Show and astronaut Neil Armstrong—who just a few months before had become the first man on the moon—tried out their material before taking it to Vietnam.

As with all great comedians, dissecting contemporary culture, politics and changing societal mores was a Hope staple. Widespread recreational drug use in America and among troops in Vietnam had become a comedic target by 1970 and a part of Hope’s routine. With all-star Cincinnati Reds catcher Johnny Bench as his foil, Hope chimed: “Where else can you spend eight months on grass and not get busted?”

With steady troop withdrawals in the early ’70s:

“Wonderful to be working with you leftovers!”

But even Bob Hope couldn’t escape criticism in 1970 when he made references to drug use by the troops. NBC removed most of the drug jokes prior to its January broadcast. But, at a show at the 101st Airborne Division’s base, Hope got huge laughs during his opening monologue when he said: “I hear you guys are interested in gardening here. Our security officers said a lot of you are growing your own grass. I was wondering how you guys managed to bomb Hanoi without planes!”

Hope never knew when the brass would show up, but every year Generals William Westmoreland, Creighton Abrams and Fred Weyand and Admiral John McCain would find him on stage somewhere to thank him and his crew.

Decades removed, Bob Hope’s material still holds its own, and his jokes about military life ring as true now as they did then. Perhaps most jarring to today’s viewers, however, are his apparent sexist references to women during the shows. Hope was a man of his time, referring to his female performers as “girls,” frequently commenting on their measurements—nothing atypical for the era. His jokes were also harsh and sometimes negative about the countries where the troops were stationed.

The Bob Hope Christmas tours continued to go to Vietnam until 1972. On the last tour, the group spent less time in Vietnam because of the drastic decrease in the number of American troops by then. That year Hope greeted the Marines at Da Nang with, “Wonderful to be working for you leftovers!” But, he quickly added: “You guys are lucky because you get to go home, not like our representatives at the Paris Peace Talks.”

While steady troop withdrawals meant smaller audiences, there was no less commitment and enthusiasm from the performers. And even though they spent less time in Vietnam, the grueling 1972 Christmas tour lasted more than two weeks with shows at bases in the Philippines, Singapore, Guam and a Christmas morning performance for 1,200 SeaBees at Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean.

Clearly, after nine consecutive Christmas trips to Vietnam, Hope was tired, and he was also suffering from a serious eye condition. In addition, he was increasingly criticized because of his vocal support for a war that much of the public had turned against. Vietnam tore the nation apart and Hope got caught in the fray. After more than three decades of making troops around the globe laugh during wartime and peacetime, he found himself defending his commitment. For those who saw him perform in Vietnam, his shows made them feel they were not forgotten in an unpopular war and that their sacrifices—in their war—were as important as the “Big One” in which their fathers fought.

Clearly, after nine consecutive Christmas trips to Vietnam, Hope was tired, and he was also suffering from a serious eye condition. In addition, he was increasingly criticized because of his vocal support for a war that much of the public had turned against. Vietnam tore the nation apart and Hope got caught in the fray. After more than three decades of making troops around the globe laugh during wartime and peacetime, he found himself defending his commitment. For those who saw him perform in Vietnam, his shows made them feel they were not forgotten in an unpopular war and that their sacrifices—in their war—were as important as the “Big One” in which their fathers fought.

During the final montage of photos and film of his last televised Vietnam Christmas special in 1972, Hope narrates film footage of Long Binh shot a year earlier, bustling with troops. “Well,” he said, showing the new footage of a deserted Long Binh, overgrown with weeds, “this is how [it] looks now…and this is how it should be…all those happy, smiling, beautiful faces are gone. But most of them are really where they belong, home with their loved ones.”

Judith Johnson recently retired as a professor and history department chair at Wichita State University. She is now working on a study of private contractors during the Vietnam War. For more on Hope, she recommends: Bob Hope, A Life in Comedy by William Robert Faith, and Five Women I Loved: Bob Hope’s Vietnam Story by Bob Hope.