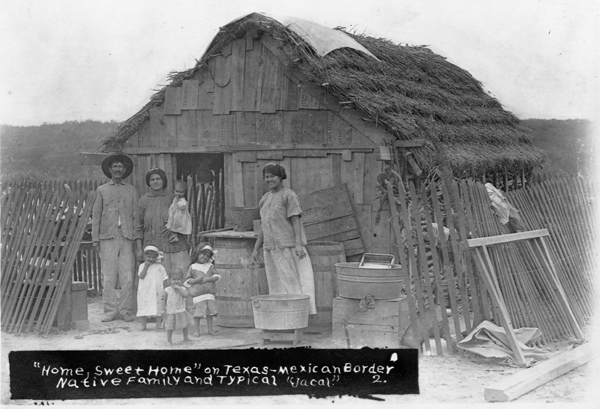

The trouble came when railroads laid tracks into the lower Rio Grande Valley. Many agreed the iron rails helped set in motion the South Texas Revolt of 1915, aka the Bandit War. Until then the valley had been relatively homogeneous, its Hispanic population getting by on small ranches and farms. If not for the river border, it would have been impossible to distinguish the Mexican stretch of the valley from the section that fell within the boundaries of Texas. The land had been part of the United States since the 1846–48 Mexican War, but due to a lack of transportation routes, it had remained remote to most Anglos.

By the turn of the 20th century railroads were still virtually absent from the valley, but market pressures filled that void over the following decade. The climate and soil were ideal for growing fruits and vegetables—items that brought top dollar in big city markets. Railroad companies promoted it as the “Magic Valley,” a promised land of quick wealth, and their trains soon began to unload hordes of Anglos with money in their pockets for buying up land. The Saint Louis–based John T. Beamer Co. became the area’s largest economic player, investing $3.5 million in a canal system, a town site and 100,000 acres for farming citrus fruit.

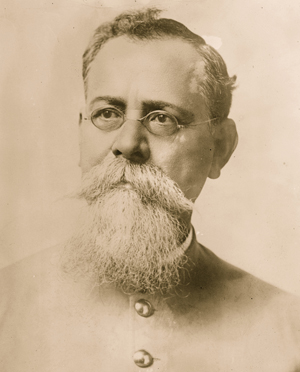

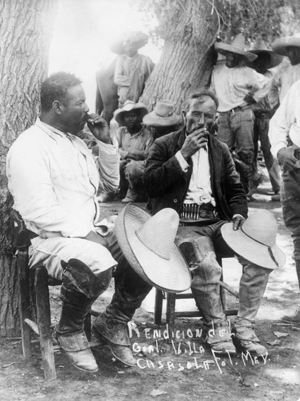

The new arrivals elected their own public officials, some of whom took to auctioning Hispanic properties seized through tax liens in the rush to open up ever more land. Soon many of the longtime inhabitants found themselves working for the newly arrived Anglos. Bitterness was in the air. The Hispanics could not turn to their ancestral homeland for help. Across the river civil war gripped Mexico. Since forcing the resignation of de facto dictator Porfirio Díaz in 1911, such revolutionary figures as Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata had become embroiled in a multisided power struggle. In 1915 Carranza wrested control of the south bank of the lower Rio Grande.

That January a Mexican named Basilio Ramos crossed the river from Matamoros into Brownsville, Texas. There was nothing unusual about that. Thousands crossed the border each day without being checked. But concealed beneath his coat Ramos carried a copy of a manifesto called the Plan of San Diego. Drafted by Mexican rebels in the south Texas town of San Diego, it called for the Hispanic population of the Southwestern United States to rise up in armed rebellion, overthrow the oppressive Anglos and reclaim all lands the federal government had taken from Mexico in the Mexican War. The Sedicionistas behind the proposed race war called for the extermination of every Anglo male over age 16 and encouraged the cooperation of American Indians and blacks, who would be given their ancestral lands or land of their own to settle.

Ramos’ task was to seek Tejanos (Texans of Hispanic descent) willing to join the Sedicionista “army of liberation.” His mistake was in approaching Dr. Andres Villareal, a Tejano with U.S. sympathies, in the border town of McAllen, some 60 miles west of Brownsville. Villareal informed the city marshal, who arrested Ramos and turned him over to federal authorities. Transported back to Brownsville, Ramos was held in the Cameron County Jail while awaiting a court date.

Even as Ramos cooled his heels behind bars, Villistas and Carrancistas battled for control of the valley south of the river. Carranza’s army finally took the region after breaking the siege of Matamoros on April 13 and routing Villa’s army. From then on no one could cross the border to or from Texas without the approval of Carranza or his generals. There were exceptions.

The Department of Justice indicted Ramos for conspiracy to commit treason on May 13, a judge setting his bail at $5,000. When the judge reduced it to $100, compatriots posted bond. Ramos promptly skipped out and crossed the Rio Grande back into Mexico, where Carrancista officers reportedly fêted him.

The Plan of San Diego underscored precisely what U.S. authorities had feared from the Mexican Revolution—a Hispanic uprising in Texas. Such fears seemed warranted when on the Fourth of July some 40 mounted Mexicans raided the Los Indios Ranch in Cameron County. Five days later an employee of the Norias division of the legendary King Ranch shot dead one member of a raiding party. At a dance outside Brownsville on July 11 two Hispanic police officers were shot from ambush, one later dying from his wounds. Over the next two weeks the lower Rio Grande Valley lit up with raids on outlying Anglo ranches, shots fired at lawmen and assassination attempts on Anglo ranchers.

On July 25 the raiders tried cutting off the valley from the rest of Texas by burning a bridge on the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico Railway near Harlingen, Texas. That same day a U.S. Army patrol had its first encounter with a raiding band. One soldier was killed, while the pursuing detachment captured three raiders.

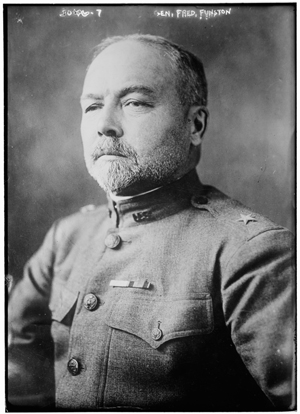

Although local newspapers and lawmen were calling the raiders “bandits,” what caught the attention of the U.S. Army and Texas Rangers was the fact the Sedicionistas had also cut the telegraph wires at Harlingen. Insurgents do such things, not bandits. That was certainly the view of Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston, who commanded the U.S. Army’s Southern Department from Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. Another factor troubling both Funston and U.S. Congressman John Nance Garner (who later served as Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president) was the seeming ease with which the raiders were able to cross the border, seldom challenged or hindered by Carrancistas. As Funston saw it, the insurgents were operating with Carranza’s tacit approval, if not his outright blessing. Garner agreed, but neither could convince President Woodrow Wilson of the extent of the problem in south Texas.

Regardless, authorities needed to stop the insurgents. Funston arranged for a special train to transport soldiers to the Brownsville border country from Fort McIntosh in Laredo, while Texas Governor James Ferguson sent a company of Texas Rangers on a “pacification campaign” directed by Captain Henry Ransom.

“Cold-blooded as a rattlesnake” was how famed Ranger Frank Hamer described Ransom, whose law enforcement career had been a mixed bag. He’d been a deputy sheriff in Fort Bend County before becoming a Texas Ranger in 1905. Two years later he resigned to become a ranch manager, only to return to the Rangers in 1909. A year later Houston Mayor Horace Baldwin Rice hired Ransom, a fellow former Ranger, and two other men as special officers to clean up that city. Ransom soon came under a cloud after shooting dead a prominent criminal defense attorney, though he was acquitted on a plea of self-defense. In 1912 Mayor Rice appointed him police chief, but Ransom had to move on after his handpicked force, which included several Ranger buddies, racked up charges of excessive use of force. Ransom later managed a Texas prison farm.

On July 20, 1915, Governor Ferguson commissioned Ransom as captain of newly formed Texas Ranger Company D. Assuring the captain of his pardoning power, the governor ordered Ransom to clean up the lower Rio Grande Valley by any means he deemed necessary.

‘I then proceeded to my son Charles, who was lying a few feet from his father. I found his face in a large pool of blood and saw that he was shot in the mouth, neck and in the back of the head and dead when I reached him’

A murder raid near Sebastian on August 6 galvanized Texas’ Anglos against Hispanics in general. Alfred Lyman Austin and his adult son Charles had taken a break from working the corn harvest when 14 heavily armed Sedicionistas rode into town. The raiders robbed a local saloon, looted the general store, stole horses and burned several outbuildings before heading to the Austin farm.

“The father was said to have been a very hard taskmaster and unused to the ways of the Mexicans,” recalled Deputy Sheriff Virgil Lott, adding Austin had a reputation of putting his boot to Mexican field workers if their work was unsatisfactory. Among the raiding party were some of the workers who had been thus abused.

Nellie Austin was in the kitchen, cooking a hot meal for her husband and son, when the raiders burst in and dragged Alfred and Charles from the house. Nellie soon heard a series of shots from the direction of the field. Rushing outside, she found Alfred with two bullet holes in his back. “My husband was not quite dead, but died a few minutes thereafter,” Nellie later reported in an affidavit. “I then proceeded to my son Charles, who was lying a few feet from his father. I found his face in a large pool of blood and saw that he was shot in the mouth, neck and in the back of the head and dead when I reached him.” The violence only escalated.

On the evening of August 8 upward of 50 Sedicionistas again descended on the southern end of the King Ranch at Norias. Leading them was Luis de la Rosa, a 50-year-old former deputy sheriff of Cameron County, who sported a mustache streaked with gray and was missing two fingers from his left hand. A self-taught Marxist, he had emerged as one of the natural leaders of the insurrection.

Earlier that day local ranch hands had spotted de la Rosa and his men riding north, prompting Norias manager Caesar Kleberg, then in Brownsville, to appeal to the Army and the Rangers for help. Texas Adj. Gen. Henry Hutchings immediately organized for the special train to be sent north to Norias, whose two-story ranch house doubled as a St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico flag station. Aboard the train were Hutchings, 12th U.S. Cavalry Corporal Allen Mercer and seven troopers, and two companies of Texas Rangers captained by Ransom and Monroe Fox. The train arrived at the ranch about the same time as the raiders.

De la Rosa had forced elderly Norias rider Manuel Rincones to guide his men to the ranch house. As the train rolled to a stop, the Rangers and other King Ranch cowboys charged off past the insurgents, who were hiding in the thick chaparral. The raiders had no intention of taking on Texas Rangers. They knew that only foreman Frank Martin (a former Ranger) and carpenter George Forbes lived at the ranch house. What they didn’t know is that Mercer’s troopers had arrived, as well as Cameron County Deputy Sheriff Gordon Hill, two customs inspectors and an immigration inspector, who had also responded to the call for help.

At 6 p.m. customs inspector Marcus Hines was on watch at the ranch house when the raiders came galloping up, dismounted and began firing. Foreman Martin, carpenter Forbes and two soldiers were wounded in the first exchange. But de la Rosa had failed to cut the telephone line, thus the defenders were able to put in a frantic call to boss Kleberg for men and ammunition.

The gun battle raged two and a half hours, leaving the cavalrymen, three of whom had been wounded, desperately low on ammunition. The decisive action occurred around 8:30 when de la Rosa led a determined charge against the ranch house. The insurgents got within 40 yards before breaking and running. They left behind four dead. The only Norias fatality was a Hispanic woman whose husband was a section hand for the railroad. The attackers had captured her during the fight and demanded she reveal how many were in the ranch house. When she told de la Rosa to go find out for himself, he shot her in the mouth in front of her son.

At 10 p.m. a relief train arrived with reinforcements, as well as a railroad surgeon, who treated the five wounded men in the house. An hour later a train from Brownsville arrived with more reinforcements. But de la Rosa and his raiders had vanished in the chapparal.

The other most-wanted insurgent leader was Aniceto Pizaña. He was a tragic figure. Though he empathized with Mexican revolutionaries, he’d remained a peaceful and respected Tejano rancher. All that changed after a covetous neighbor told authorities Pizaña was harboring fugitive raiders. At dawn on August 3 a posse of soldiers, deputies and civilians—some 30 men in all—hit the ranch, and Pizaña and his ranch hands immediately opened fire, killing one of the soldiers. In the exchange that followed, the rancher’s 12-year-old son was wounded in the right leg, which later had to be amputated. Pizaña himself fled on horseback. Arrested at the ranch, his brother, Ramon, was charged with complicity to murder. At that point Pizaña crossed the river and promptly joined the Sedicionistas. Though he led a few raids into Texas, mostly night attacks on ranch houses and railroad infrastructure, he proved more effective at recruitment and training of the guerrilla forces.

The Sedicionistas didn’t just target white Texans. Prosperous Tejanos and those who joined posses or otherwise assisted the Anglos also paid a price.

A favorite target was Tejano landowner Florencio Saenz, whose holdings comprised more than 40,000 acres, outbuildings and the general store in Progreso, on the border in eastern Hidalgo County. That summer raiders repeatedly struck at Saenz, rustling horses and looting his store and outbuildings until soldiers arrived to chase them off. On September 2 two cavalry troops and a posse of deputies under Sheriff Anderson Yancy Baker engaged a band of 40 raiders in Progreso. The skirmish stretched into a four-day gun battle. On the fourth day Baker, in a bid to lure the raiders into the open, feigned collapse, as if shot. When the Mexicans took the bait and emerged to “finish off” the sheriff, the posse and soldiers killed several of them.

Three weeks later 80 Sedicionistas mounted an early morning raid on Progreso, seeking to dynamite Saenz’s general store. A dozen soldiers were waiting for them. The raiders had gotten the upper hand, having killed one soldier and wounded another, when a cavalry troop rode up. During the two-hour clash that followed, the raiders captured Private Richard Johnson and took him back across the Rio Grande into Mexico. After torturing the trooper, they cut off Johnson’s head and displayed it atop a pole near the border bridge.

Rangers, local lawmen and vigilantes also took a toll on Tejanos. Amid the heightened racial tension, suspicions ran high. On August 6, the day of the Austin murders, a posse of local lawmen and Rangers, including Captain Ransom, shot down an unarmed Desiderio Flores and two of his sons on their ranch near Harlingen on mere suspicion they were harboring the killers. A passing Army patrol helped the family’s women bury their dead. Other encounters were more sinister. Years after serving on the border as a U.S. Army private, Adam F. Medveczky recalled having watched Sheriff Baker kill three captive Mexicans in cold blood. “He was killing Mexicans on sight,” Medveczky said.

Army scout John Randall Peavey came across a disturbing sight—the bodies of 11 raiders dangling from roadside trees near the village of Los Ebanos. For good measure, each had been shot in the forehead, execution style. The inference was clear. ‘People were shooting first and not talking afterward,’ Peavey recalled

Recriminations between the combatants also grew worse. In late September Ransom’s Rangers engaged in several skirmishes with Sedicionistas along the Hidalgo County border. On the 28th Army scout John Randall Peavey was escorting the military district commander west along the river road to Fort Ringgold when they came across a disturbing sight—the bodies of 11 raiders dangling from roadside trees near the village of Los Ebanos. For good measure, each had been shot in the forehead, execution style. The inference was clear. “People were shooting first and not talking afterward,” Peavey recalled.

In the early morning hours of October 19 a band of Sedicionistas lying in ambush just north of Brownsville derailed and attacked a passenger train. The engine, tender and express car rolled over, crushing the engineer and scalding the fireman. District Attorney John Kleiber was aboard the day coach, which remained upright, and he ducked low as the attackers fired repeated volleys into the air, presumably to cow the passengers. Four raiders then boarded the coach. They immediately shot a soldier to death and wounded three other passengers. After assuring a Hispanic family they would come to no harm, the raiders then robbed Kleiber and the other Anglos. Before leaving the coach, they shot through the bathroom door, mortally wounding a doctor hiding inside.

Retribution was swift and merciless. In the hours following the attack, at least 10 raiders turned up dead. Ransom had another four suspected raiders in custody, and Cameron County Sheriff William T. Vann had two others. As Vann later testified at an inquiry, Ransom told him he was going to kill both his and Vann’s prisoners for their involvement in the derailment. Vann refused to comply, telling Ransom he did not have enough Rangers to force him to turn over the two men. The sheriff then returned to Brownville with his captives, who were later proven innocent.

Well into that fall soldiers and civilians came across dead Mexicans all along the border. How many were killed will never be known. Texas Ranger historian Walter Prescott Webb cited a low estimate of 500, while the anarchist newspaper Regeneración claimed 1,500 Mexicans were murdered in Texas during the Sedicionistas’ campaign. In the Brownsville district alone federal investigators determined 300 Hispanics were hanged or shot in cold blood. While some were undoubtedly raiders, others were simple citizens caught up in the killing frenzy. “How many lives were lost cannot be estimated fairly,” wrote south Texas newspaperman Virgil Lott, “for hundreds of Mexicans were killed who had no part in any of the uprisings, their bodies concealed in the thick underbrush and no report ever made by the perpetrators of these crimes.”

Entire Tejano families left their farms and ranches and crossed the river, opting to take their chances in war-torn Mexico rather than risk death at the hands of vigilantes and trigger-happy Rangers. Ransom boasted of burning down homes and destroying crops in their absence.

The U.S. Army began actively intervening against the Rangers. On September 17 the Hispanic settlement of San José, north of Brownsville, asked for and received a guard of soldiers as protection against the Rangers, and in mid-October cavalry troops were posted to the town of Los Indios, on the border south of Harlingen. General Funston complained to both President Wilson and Governor Ferguson about the Ranger excesses and ordered that any Rangers riding with soldiers or troopers do so under strict Army command. Officers afforded what protection they could to Hispanic families. A few local lawmen refused to assist the Rangers, and Vann had three Rangers arrested on murder charges.

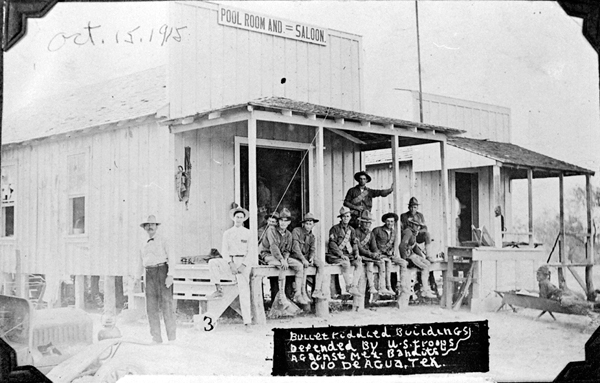

On October 19, within hours of the train attack north of Brownsville, President Wilson formally recognized Venustiano Carranza as de facto president of Mexico. On the 21st, rebels assaulted the U.S. Army Signal Corps station at Ojo de Agua before reinforcements drove them back to Mexico. Sedicionista raids along the Rio Grande sharply decreased after that, as Mexican soldiers resumed patrols along the border. U.S. recognition may have been what Carranza had been after all along. In February 1916 authorities in Monterrey arrested Pizaña. Four months later Mexican soldiers caught up to de la Rosa. Both were eventually released and lived out their lives in Mexico.

A day of reckoning came for the Texas Rangers, ironically at the hands of a Tejano. In 1918 state representative José Tómas Canales of Brownsville started an investigation into Ranger atrocities during the border conflict. His inquiries prompted a December 11 confrontation outside the Miller Hotel with the visiting 6-foot-3, 230-pound Hamer, who was no friend of Ransom but loved his Rangers. “If you don’t stop,” Hamer told Canales, “you are going to get hurt.” Shaken by the encounter, Canales sought counsel from Sheriff Vann, who offered to have Hamer killed. “No jury would ever convict you,” Vann reassured the legislator. As taken aback by the sheriff’s bluntness, Canales turned down the offer. But he didn’t back down.

In January 1919 Canales held hearings on Ranger conduct along the Rio Grande, filed 19 charges related to border atrocities and introduced a bill calling for a restructuring of the force. In March the Texas Legislature passed an albeit watered-down version of Canales’ bill, which capped the size of the force, while increasing Ranger pay. The findings with regard to Ranger conduct along the border were such that the state House of Representatives reportedly refused to print the transcripts and kept them off-limits to the public until the 1970s. Discouraged by the whitewash of his investigation, Canales never ran for public office again.

Meanwhile, by the spring of 1918, as American soldiers geared up for a far larger war in Europe, peace had returned along the Rio Grande. Hispanic families filtered back across the river to their ranches and farms. Trainloads of Anglos arrived to buy more property. “Magic Valley” was open for business. Indeed, the South Texas Revolt marked the last serious border incident to date. WW

Frequent Wild West contributor Mike Coppock writes from Enid, Okla. For further reading he suggests The Plan de San Diego, by Charles H. Harris and Louis R. Sadler; Revolution in Texas, by Benjamin Heber Johnson; and From South Texas to the Nation, by John Weber.