The Lost Mandate of Heaven: The American Betrayal of Ngo Dinh Diem, President of Vietnam

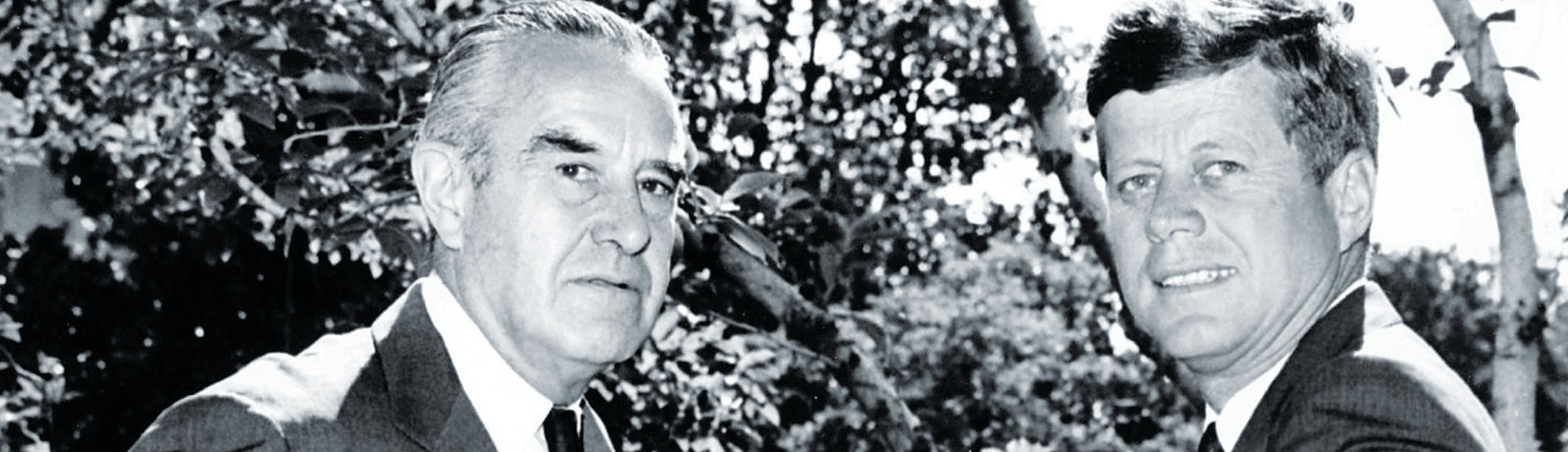

Although Vietnam War historians have been quick to criticize Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon for their errors in strategy, policy and judgment regarding America’s involvement in the war, John F. Kennedy often gets a “pass”—his name seldom appears on the “short list” of presidents who “lost” Vietnam. Geoffrey Shaw’s The Lost Mandate of Heaven, however, makes a solid case that Kennedy and his top advisers—particularly W. Averell Harriman’s influential State Department clique—orchestrated “a political disaster that led America into a protracted and costly war.” Shaw’s book reveals Kennedy’s disastrous blunders that may have lost the Vietnam War before the United States began fighting it in earnest.

As its subtitle promises, Shaw’s book principally focuses on the Kennedy administration’s “betrayal” and collusion—at the very least its acquiescence—in the Nov. 1-2, 1963, military coup that resulted in the assassination of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem.

Shaw’s image of Diem, based on extensive research, original sources and declassified documents, sharply contrasts with the widely accepted view of South Vietnam’s first president. Diem has typically been portrayed as a corrupt despot who, stubbornly ignoring American advice, mercilessly persecuted the country’s Buddhist majority in favor of his fellow Catholics. Critics also pointed to his heavy-handed rule, which alienated South Vietnam’s population and increased the risk that the war would be lost to North Vietnamese–sponsored Communist guerrillas. According to this conventional view—notably, as Shaw shows, relentlessly promoted at the time by Saigon’s American press corps, which despised Diem—the South Vietnamese president had to go and therefore the Kennedy administration justifiably colluded in his removal.

Shaw presents Diem as a dedicated leader of integrity, a popular Vietnamese nationalist deeply committed to his Catholic faith’s tenets, firmly resolved not only to protect his country against North Vietnamese aggression but also to resist becoming merely a figurehead and pawn of the Americans. Calling Diem’s murder “a mistake of unparalleled proportion,” Shaw asserts that it robbed South Vietnam of the only leader whose fame, stature and nationalist credentials rivaled those of the North’s Ho Chi Minh. No subsequent South Vietnamese leader proved capable of inspiring the country’s population with the fervor necessary to successfully resist North Vietnam.

Even if you are unswayed by Shaw’s revisionist presentation of Diem’s character and leadership, you have to question the Orwellian logic of the Kennedy administration’s support for his removal: Led by the Harriman faction, Kennedy’s top advisers concluded that Diem was not “democratic enough” to suit them, so they colluded in a bloody coup d’état that murdered Diem and replaced his elected government with a military dictatorship! The Kennedy administration’s complicity in the military cabal’s coup was hardly a shining example of democracy in action. Even North Vietnam’s leadership was astonished that the United States had conspired to eliminate the South Vietnamese leader the Communists most feared.

Shaw also recounts another inexcusable Kennedy blunder that arguably was his administration’s worst mistake directly influencing the war: the egregiously inept decision binding the United States by international treaty to officially honor the “neutrality” of Laos. Signed in Geneva on July 23, 1962, by the United States and 14 other nations—notably North Vietnam and its principal Communist supporters, China and the Soviet Union, who enthusiastically approved it—the one-sided treaty, based on “unenforceable neutrality,” was a farce from inception.

Hanoi immediately violated the agreement, sending thousands of North Vietnamese Army troops (joining Laotian Communist allies, the Pathet Lao) to occupy Laos’ entire eastern half and construct the extensive logistical network, known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was vital for North Vietnam’s prosecution of the war. North Vietnam had maintained logistical routes and bases in Laos since at least 1958 to supply Viet Cong guerrillas in South Vietnam.

It is hardly an exaggeration to state that every American killed in ground combat in South Vietnam during the war died from a bullet, rocket-propelled grenade, mortar round, artillery shell or hand grenade brought south via the Ho Chi Minh Trail. There was no other practical means for Hanoi to get the instruments of death south other than through “neutral” Laos.

Thanks to Kennedy’s unconscionably foolish Laos treaty—“forged by Harriman,” Shaw points out—North Vietnam had free rein to exploit this monumental advantage. Although the United States bombed the Laotian trails, the massive effort was disappointingly ineffectual. And the ill-fated 1971 Laos incursion by U.S.-supported South Vietnamese ground troops proved far too little and much too late.

Shaw’s insightful book shows that Vietnam War historians must stop giving Kennedy a pass. Clearly, Kennedy has blood on his hands—Diem’s and that of an untold number of American GIs.

First published in Vietnam Magazine’s August 2016 issue.