The Civil War was only four months old, but Union Navy officer Lewis H. West was quite sure the Federal blockade of Southern ports was inadequate. In August 1861, while on duty at Alexandria,Virginia, he complained that Rebel privateers could “come and go as they please” with little interference from Union vessels. One year later, when he was serving off Charleston on USS Lodona in the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, his attitude hadn’t changed a bit.

“The blockade is much the same as it always was,” he groused in a letter home. “There has not been a night for the last two weeks that steamers have not run in and out, not one of which have been captured; and so it will probably go to the end.” West was correct in that assessment, for while Confederate commerce did suffer from maritime seizures and restrictions, but the Southern economy did not collapse from the Union naval blockade. Official war records and many other sources suggest that wartime traffic in and out of many Southern ports actually equaled or surpassed prewar volumes.

The sievelike naval picket line was a constant source of embarrassment to members of the Lincoln administration. “I am fairly oppressed by the insufficiency of the blockade,” Rear Adm. S.F. DuPont wrote to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles in August 1862, commenting on the blockade at Charleston.“I think it probable that some two million sterling of arms and merchandise have gone in the last ten days.”

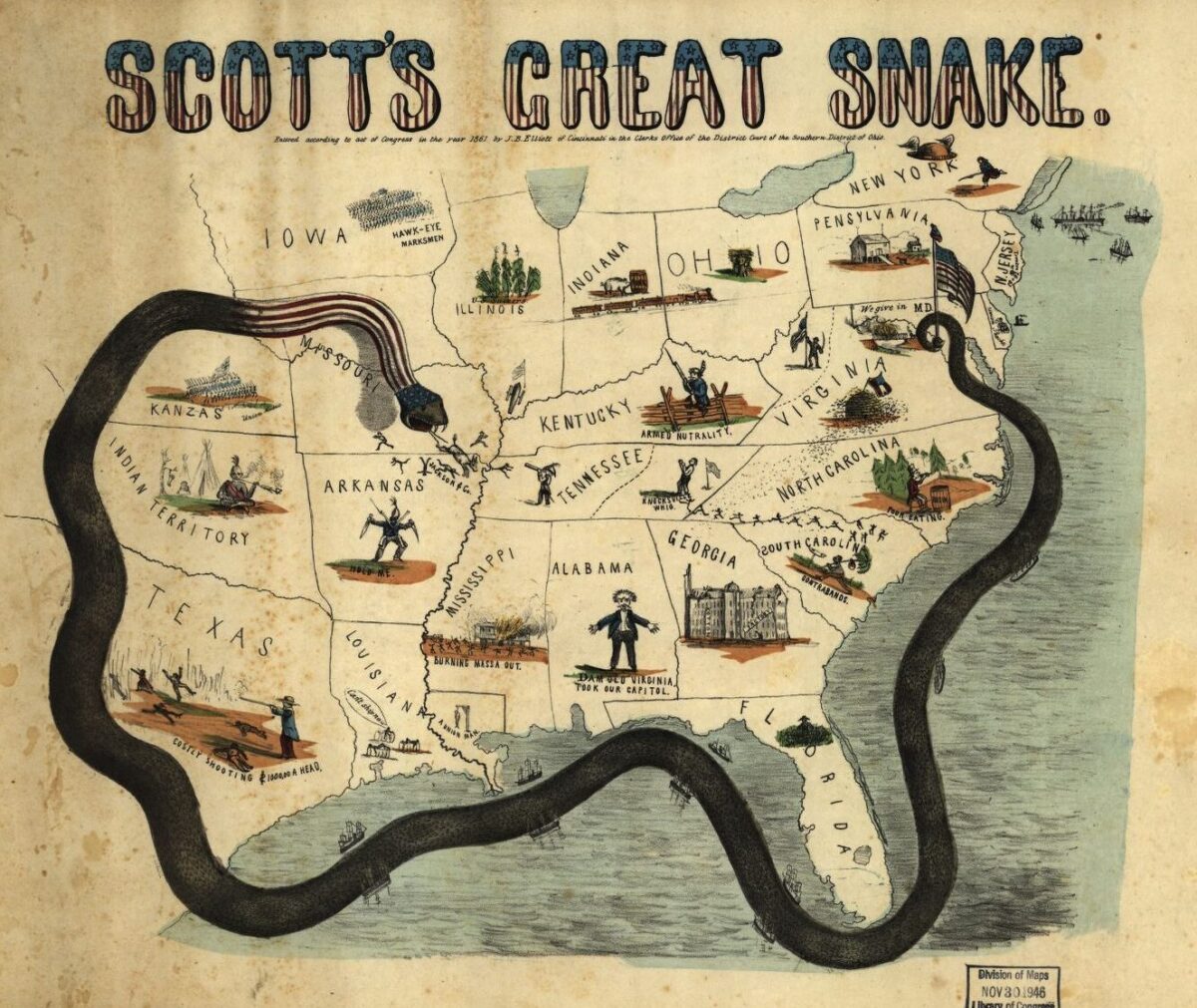

The naval blockade was part of the Anaconda Plan, developed at the beginning of the war by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott. The plan called for a variety of land operations in addition to strangling the Confederacy by cutting off or capturing the South’s dozen or so largest ports. Scott was a military hero and wise in the ways of war, but his plan for a blockade harkened back to the war against Mexico, when the American Navy had faced a preindustrial enemy with a long, largely empty coastline. The game would be much different this time around.

Scott’s plan for a blockade was given official sanction on April 19, 1861, when President Abraham Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Blockade Against Southern Ports. The proclamation called for a “competent force…to be posted as to prevent entrance and exit of vessels” from Confederate ports. It also laid out an elaborate protocol that stated warnings should be issued and documented before a vessel violating the blockade could actually be captured.

Part of the new plan involved Welles’ creation of a Blockade Strategy Board. The board determined where to target ports and where to locate refueling and refitting bases—many of which had to be captured from the Confederates. Three blockading squadrons were established. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was assigned to keep an eye on the Virginia and North Carolina coasts, and the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron patrolled from North Carolina to Key West, Fla. The Gulf Blockading Squadron monitored activity in the Gulf of Mexico from Key West to the border with Mexico. But the gulf proved to be too much for one squadron to handle, and the zone was split into two sections, east and west, in 1862.

When the plan was announced in 1861, many naval experts suggested that no blockade could possibly control the more than 4,000 miles of Confederate coastline; time and effort would be better spent, they said, controlling the half dozen largest port cities to shut down Southern trade. Even that lowered expectation, however, did not prove entirely feasible.

In some cases, lazy prewar ports became thriving commercial trade centers during the conflict. A convincing argument can be made on that basis alone that the blockade was a tactical failure, and probably hindered other important strategic endeavors by tying down vital Union resources. The Union Navy reported by war’s end that 1,504 blockade runners worth approximately $35 million (or nearly $1 billion in current dollars) had been captured or destroyed. Data from 1863 for the ports of Wilmington and Charleston suggest the average number of runs into those ports between 1861 to 1865 was 4.69 trips per blockade runner. Similar ratios emerge when calculating for other ports.

During that same period and at those same two ports, 119 vessels were captured or destroyed. Extrapolating from that data, it can concluded that over the course of the war four or five successful runs were made for every capture or destruction of a blockade runner. Using the Union Navy’s own numbers, that means that the Confederacy likely benefited from more than 7,000 successful runs. It is likely that more than 10,000 attempts were made to run the blockade, since ships were regularly taken out of service, lost to accidents and repairs or removed for reasons other than capture or destruction at the hands of the Union Navy.

That is not evidence of a successful blockade. Wilmington, N.C., serves to illustrate the point. In May 1861, only two Federal ships were on blockade duty for the entire 400 miles or so of North Carolina coastline. Wilmington was a premier deep-water port with a complex network of channels that made bottling it up from the ocean side nearly impossible without controlling the city or nearby forts, primarily Fort Fisher, with land forces. On July 21,1861, a small converted merchantman took up station outside the main channels on blockade duty. Faced with such feeble opposition, pro-Southern merchant ships entered and left Wilmington at will in the early part of the war.

Even in 1864, after significant efforts had been made by the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron to stop North Carolina trade, more than 300 ships made it in to Wilmington, bringing in desperately needed supplies for General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. During that same period only about a dozen ships were captured or failed in their attempt to run into port.

Arguments have been put forth that blame the Confederate defeat on the fact that profiteering owners and captains of blockade runners filled most of their hulls with overpriced luxury goods at the expense of vitally needed war material. Profiteering from private cargos run through the blockade likely was a contributor to inflation. But reliance on an unstable and fiat paper currency, the withholding of the 1861 cotton crop from overseas distribution and a shortage of specie and gold were also prime contributors. In fact, the profit motive was the necessary engine that fueled almost all blockade running.

The truth is that while evasion of import duties or violation of government cargo restrictions was a fact of life in some smaller ports and more remote coastal hideaways, the South imported massive amounts of war materiel through the blockade, and the Confederate government maintained customs offices in all major ports to collect taxes and to ensure that the portion of any cargo reserved for the government was actually delivered.

One account reports that the Confederacy imported more than 600,000 individual firearms through the blockade, easily enough to equip every Rebel soldier in every theater. Single order manifests for as many as 100,000 arms are extant in the papers of President Jefferson Davis’ War Office records. Importation of arms was not a problem, therefore. The problem was with transportation, once ashore.

The South’s horrendous system of internal transportation constantly interfered with efficient disbursement of goods to the armies in the field. When Lee’s bedraggled army surrendered at Appomattox in April 1865, warehouses throughout the Confederacy were stuffed with thousands of yards of cloth, barrels of bacon, bars of pig iron, tons of salt and many other items a struggling industrial economy needed to make war.

In three months alone in late 1864, approximately four million pounds of meat, nearly four million pounds of lead and saltpeter and almost half a million pairs of shoes were imported. Some luxuries, such as silk, did come into those ports during that period, but they were simply not heavy enough or available in enough quantities to affect the overall importation of war-related supplies.

The trade ran in both directions. After an initial policy of withholding the cotton crop from export, the Davis administration opened the floodgates, and practically every runner leaving port had cotton bales in the hold or stacked on deck. The blockade runner R.E. Lee took out 6,000 bales worth about $2 million in gold in one year alone. No complete data are available, but using the estimates already calculated and an average of 100 bales per ship per trip out, it is likely at a minimum that more than half a million bales of cotton were successfully exported during the war, worth somewhere in the neighborhood of $200 million in gold.

There is even evidence that Northern merchants imported cotton through third-party agents in Caribbean ports, and Yankee coffee, salt and other articles ended up on Confederate tables in return. Loyal Confederates observing this unscrupulous war trade, which benefited the cotton-hungry Northern economy, were outraged and even implied that the Union fleet may have intentionally permitted some Northern-bound cargos to slip through the blockade to neutral ports.

The Union Navy failed to capture most of the major Southern ports until late in the war. Wilmington’s Fort Fisher, for example, was not captured until January 15,1865, just a few months before the war ended. In addition, throughout the conflict the Navy failed or simply could not deploy its resources widely enough to stop traffic through small inlets and intercoastal waters. Even a series of minor port cities like Tampa, Fla., Georgetown, S.C., and Brunswick, Ga., continued to serve effectively as out of the way ports of call for smaller, more elusive cutters and blockade runners. Tampa, for example, was still open to blockade-running traffic even after Lee’s surrender.

Based on records and maps from the period, it is estimated that the South had more than 200 minor port cities, places that could handle intercoastal shipping or smaller oceangoing vessels and potentially move cargo inland to larger transportation hubs. Even the largely uninhabited Florida coast received innumerable clandestine shipments from Nassau, Havana and Bermuda that directly or indirectly supported the Confederate cause. The very nature of many blockade runners’ intentionally hidden activities makes it very difficult to know just how many unofficially got through.

Blockade runners even transported people. Foreign dignitaries, women and children,Confederate diplomats and even vacationers regularly booked passage on departing runners. Many coastal packet ships held close to routine schedules as they plied the waters between smaller intercoastal destinations. Some blockade runners going in and out of Wilmington were also reported as having regular schedules.

Even passengers or blockade runners steaming out of ports such as Savannah and Charleston, which were surrounded by rings of Union warships, were at much greater risk from storms at sea and from losing their crews to yellow fever than they were from high-seas warfare.

From every Confederate perspective, the benefits of running the blockade far outweighed the possible consequences.Some states, such as North Carolina, actually entered into a lucrative competition with private runners and Confederate interests. Blockade runners generally turned a profit if they made at least three trips, and the average ship made at least four to five trips. It is no wonder that speculators in England eagerly grabbed a piece of the profits—even late in the war, when land forces helped the Union Navy enforce the blockade more tightly.

Even though hundreds of runners were destroyed or captured, thousands made it through, and the success rate never fell so low that it became unprofitable for almost anyone involved. Only the capture or abandonment of ports such as Charleston, Mobile and Wilmington in the last six months of the war brought about Confederate collapse.

The majority of modern statistical or economic treatments of the blockade trace their origin to work in the 1940s and 1950s by Marcus Price, work that was not intended to be exclusive or exhaustive. Many more recent books about the blockade have tended to focus on a small number of adventurous and flamboyant firsthand accounts of blockade runners and their admirers, or the specific voyages of individual ships. Very few historians have challenged the myths and misconceptions of the blockade, or considered additional data.

Perhaps from a broad strategic perspective, historians will soon revisit Confederate grand strategy to see why priority was given to large field armies, when the vital ports, the economic lifelines, were threatened and then captured one by one by combined Union Navy and Army forces. Those defeats were often downplayed by authorities and lawmakers in Richmond. Yet their loss truly signaled the demise of the Confederacy. An unsuccessful Rebel Western army arguably drained men and resources that might have kept Eastern ports open, and could possibly have given Southerners greater opportunity for significant success in the East.

Jack Trammell is assistant professor of sociology and honors at Randolph-Macon College, and writes Civil War articles for the Washington Times and other publications. He recently received several awards for his writing, and is a frequent speaker at historical events.

Originally published in the November 2007 issue of America’s Civil War.