From 1854 to 1860, America’s newspaper headlines screamed bloody murder. Sensationalist headlines read: “Bleeding Kansas!” “Sack of Lawrence!” “Pottawatomie Massacre!” “Battle of Osawatomie!” “Marais De Cygnes Massacre!” “Much Blood Spilt!” “Murder and Cold-Blooded Assassination!” Purportedly they were relaying news of an incredibly bloody and deadly clash of anti- and pro-slavery forces fought along the Kansas-Missouri border.

No single event in the nation’s drift toward Southern secession and the armed conflict that would inevitably follow paved the road to war more than the hyped-up strife that took place for six years from 1854-1860 in eastern Kansas and western Missouri along the border between the state and the new territory.

A Media Myth?

Dramatic headlines would deepen the nation’s rapidly developing North-South rift, dividing those who fervently opposed further extension of what they realized was the country’s “original sin”—the curse of slavery—and those who stubbornly supported maintaining African Americans in chattel bondage as both constitutionally legal and essential to clinging to their wealth, livelihood and way of life. No rational person today can argue against the fact that slavery was an evil that had to be eradicated from the United States, nor can anyone deny that pro-slavery forces were fighting on the wrong side of history. The duty of historians is to investigate, determine the historical facts and accurately report those facts—in particular, historians must not perpetuate myths.

The overblown headlines, created and promoted by partisan newspaper reporting on both sides, misrepresented what was actually happening west of the Mississippi River along Kansas territory’s eastern border. Newspapers championing both sides of the deeply-entwined “slavery-states’ rights” issue filled their papers with fabricated “atrocities” and overly-sanguine accounts of “pitched battles” in which casualties were actually either miniscule in number or often completely nonexistent.

This apparently horrific partisan struggle pushed the nation into its bloodiest war more than any pre-Civil War conflict, but was simply a fabrication created by the burgeoning national newspaper industry and capitalized upon by the ambitious new Republican political party to help it rally a nationwide electorate to win the White House in the 1860 U.S. presidential election.

The historical irony of so-called “Bleeding Kansas” is that over 10 times more Americans were murdered in the streets of San Francisco, California, in one year—1855—than were ever killed for their political beliefs during the 1854-1860 Border War. Simply put, “Bleeding Kansas” is an easily-disprovable albeit long-enduring myth.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act was a patched-together compromise hammered out by Illinois Democrat Senator Stephen A. Douglas and then-President Franklin Pierce, a “northern Democrat” opposed to Abolitionism but willing to compromise to dampen northern and southern firebrands. The act ostensibly promoted construction of a transcontinental railroad and the accompanying economic benefit of opening millions of acres of land to new settlement.

However, it included the “popular sovereignty” concept (introduced in the 1850 Compromise but as yet untested), permitting Kansas and Nebraska territory settlers to decide by popular vote whether they would enter the Union as “free” or “slave” states. Well-meaning—but not well-considered—“popular sovereignty” essentially made obsolete previous Congressional attempts (1820 Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850) to alleviate rising North-South sectional tensions regarding slavery’s spread.

In hindsight, the 1854 act inevitably created the political conditions in Kansas territory that, predictably, devolved into violence as pro- and anti-slavery factions clashed to influence the “popular sovereignty” vote’s outcome regarding statehood. Although initially assumed that Nebraska would become a “free state” and Kansas would enter as a “slave” state, once the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed all bets were off. “Popular sovereignty” made Kansas territory a free-for-all for anti- and pro-slavery factions. Henceforth, whichever side of the slavery question wanted to prevail in Kansas would have to fight for it.

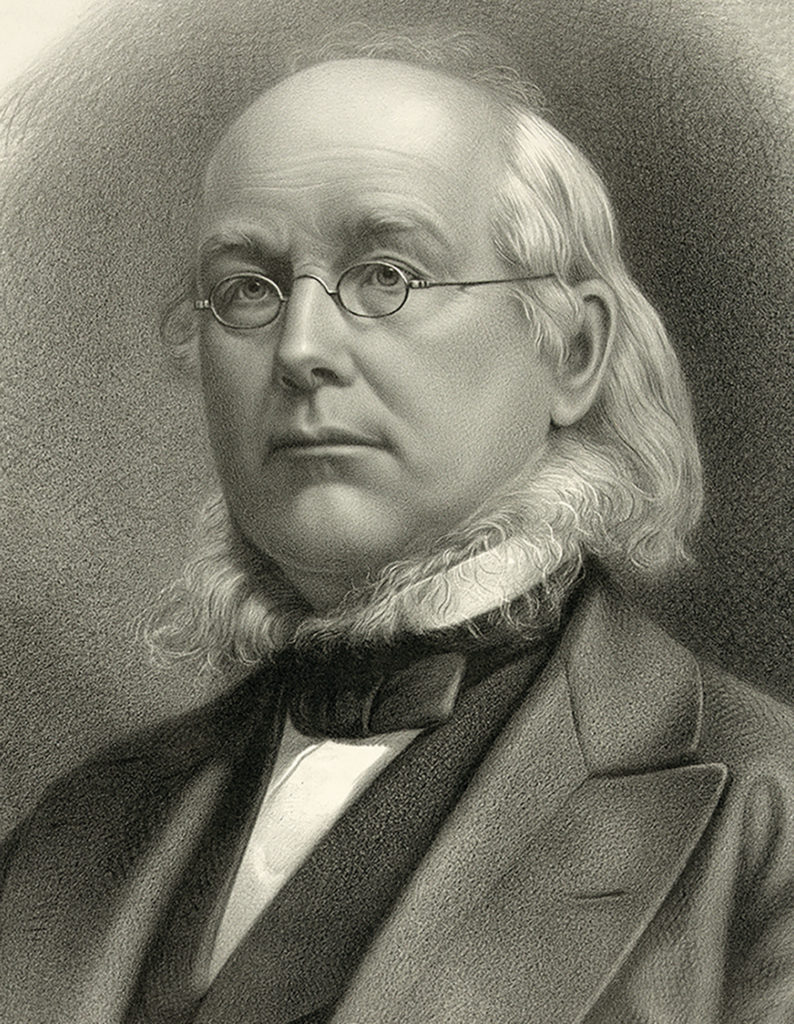

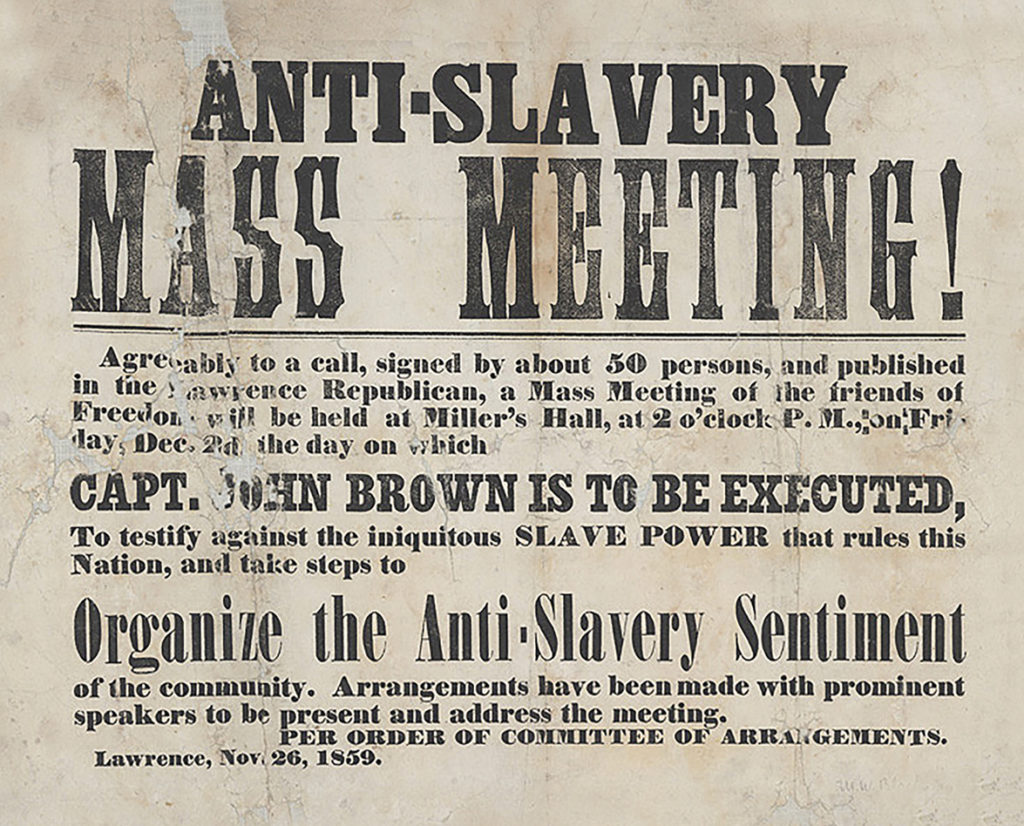

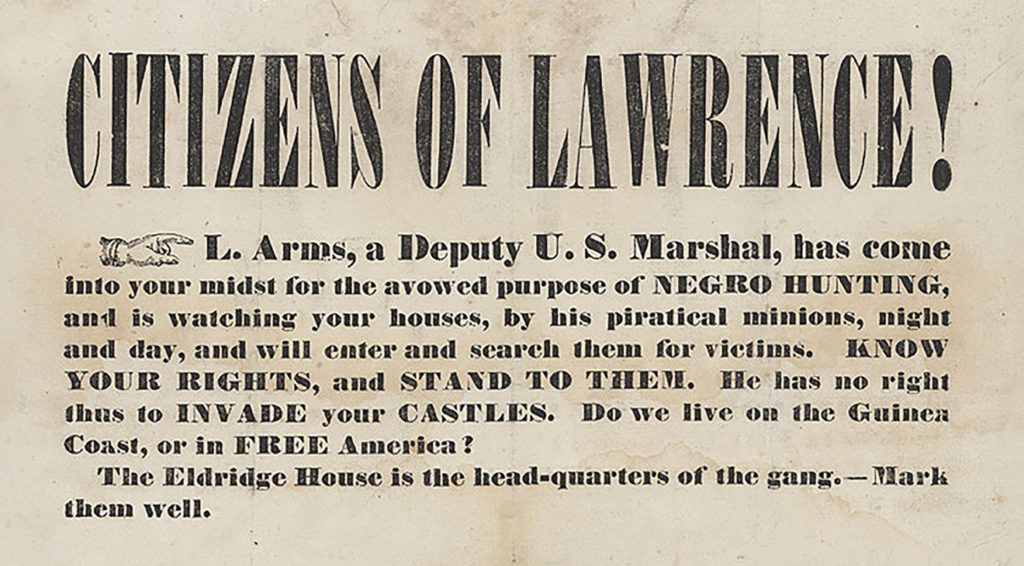

Inevitably, violence erupted along the Kansas-Missouri border in 1854, and nationwide newspapers consciously and deliberately propelled what were in fact relatively minor border clashes into a major, national political issue. The term “Bleeding Kansas” itself originally appeared in 1856 in abolitionist editor Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune to falsely describe the struggle as being one of “innocent” Free-state settlers unjustly harassed by evil pro-slavery Missouri “Bushwhackers,” thereby deliberately stoking the fires of North-South sectional passions.

Newspapers Weigh In

Yet, the truth is that despite the amplified claims of partisan newspaper editors, neither side in the Border War held a monopoly on ruthlessness and violence in pursuit of their opposing political causes.

Between 1840 and 1860, printed newspapers—daily, weekly, quarterly and periodically—underwent an explosion of overall numbers and the amount of copies printed annually. While the U.S. population then rose 180%, newspaper numbers increased 250% with total annual printed copies expanding nearly 500%.

Propelling this phenomenon were ground-breaking (labor-saving and cost-cutting) advances in printing technology. Truly “industrial scale” printing resulted from the Fourdrinier paper-making machine (U.S. introduction in 1827), which created continuous rolled paper in massive quantities and the steam-powered, continuous-feed, rotary printing press (invented in 1843 by American Richard M. Hoe).

No longer limited by laboriously printing single sheets, countless copies of a page could be produced daily. By the 1850s, illustrations were prominently featured, enhancing visual appeal, while increased staffing (typically, 1-2 in the 1820-30s; 30 in the 1840s; and 100 by the 1850s in larger papers) made it possible to fill more pages with more stories of national, regional and local interest. Advances in railroad transportation sped distribution. Improved communications (telegraph) meant widespread “breaking news.” The resulting “media blitz” was a newspaper revolution.

That era’s most influential newspaperman, New York Tribune’s Horace Greeley (editor from 1841-72), explained in 1851 how the phenomenon’s nationwide spread mirrored the country’s growth: “[T]he general rule…was for each town to have a newspaper, and, in the free states, each county of 20,000 or more usually had two papers—one for each [political] party. A county of 50,000 usually had five journals…and when a town reached 15,000 inhabitants…it usually had a daily paper and at 20,000 it had two.”

Citizens today would expect media sources to strive diligently to present the news as straightforward facts and allow the public to draw its own conclusions. However, in the mid-19th century, political partisanship in newspapers was the norm, not the exception. The “Bleeding Kansas” myth resulted from unashamedly biased newspaper reporting—each paper aggressively politically partisan and firmly committed to championing its favored side in that conflict. Editors blatantly chose sides, some aligning with the new, anti-slavery Republican Party, while others backed the then pro-slavery Democratic Party. Partisan editors graphically described the “Border War” as a war of annihilation waged by pro- and anti-slavery factions to determine Kansas territory’s future statehood status as a “free” or “slave” state.

Exaggerated Casualties

Readers nationwide became morbidly mesmerized by the “terrible casualties” reported and impatiently stood by to purchase “hot off the press” papers recounting the latest atrocities. Right was irrevocably on the side the competing newspaper editors supported, while the opposing side was accused of incredible acts of violence.

These attention-getting headlines sent circulation soaring. The atrocities described were either exaggerated or fabricated to stoke the flames of political hatred and animosity. This “spin,” in contemporary parlance, favored a particular cause or political party. A century-and-a-half ago, political parties and their media allies ignored the truth and outrageously manipulated facts.

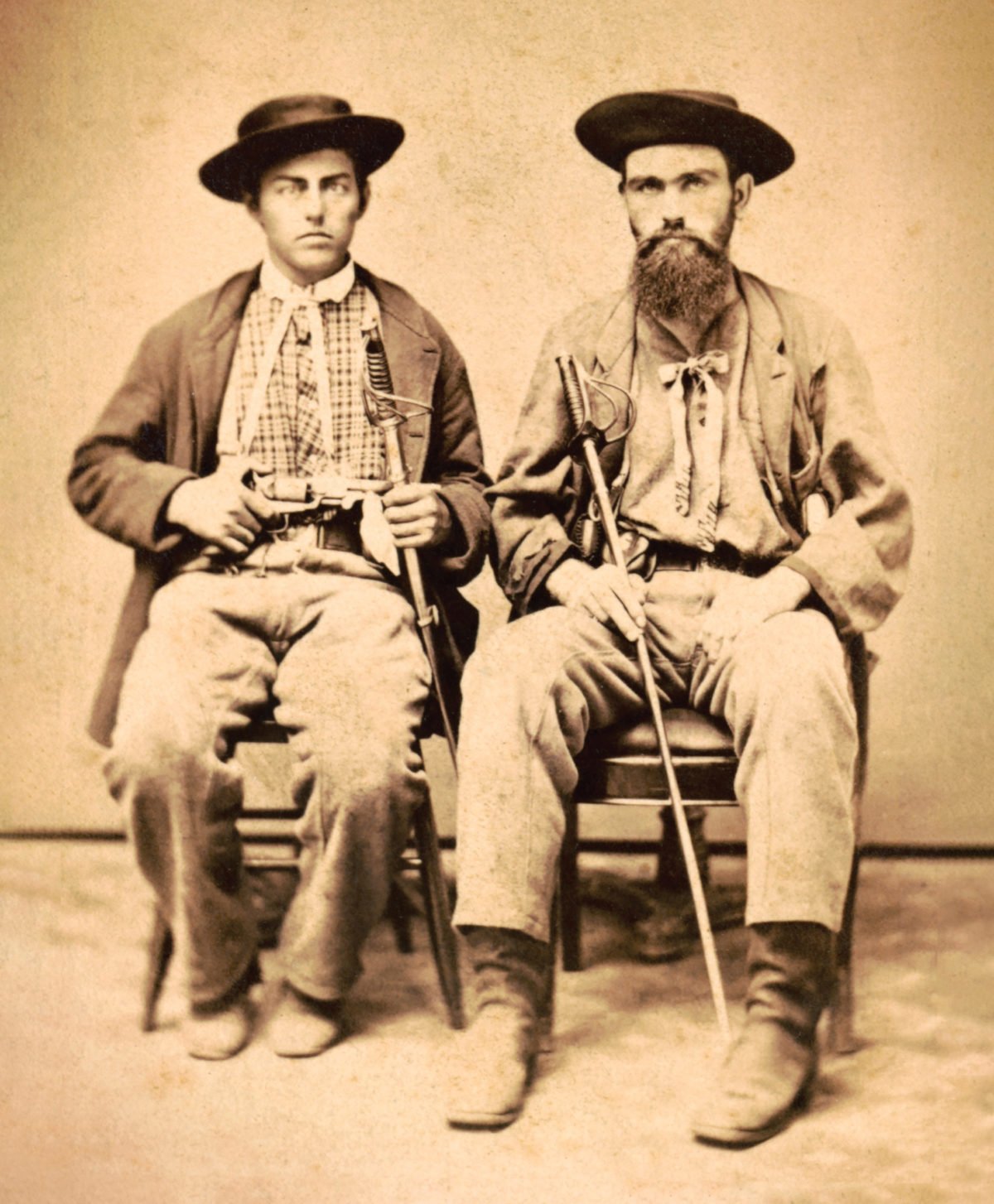

Editors profited by exaggerating the trans-Mississippi border conflict. Both sides developed derogatory names for each other; anti-slavery newspapers condemned pro-slavery forces—primarily from Missouri—as “Border Ruffians,” “Bushwhackers” and “Pukes,” while the Kansas partisans were known as “Redlegs” and “Jayhawkers.”

Created in 1854, the new Republican Party—formed of former Whigs, Free Staters and anti-slavery activists—finished a surprising second in 1856 with its first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont. In the 1860 presidential election, the party made maximum advantage of the headline-gathering Border War to expand its mainly regional electorate into a party with widespread national appeal. The new political party was eager to capitalize on the Border War to create a national voter base to promote the party’s 1860 presidential ambitions.

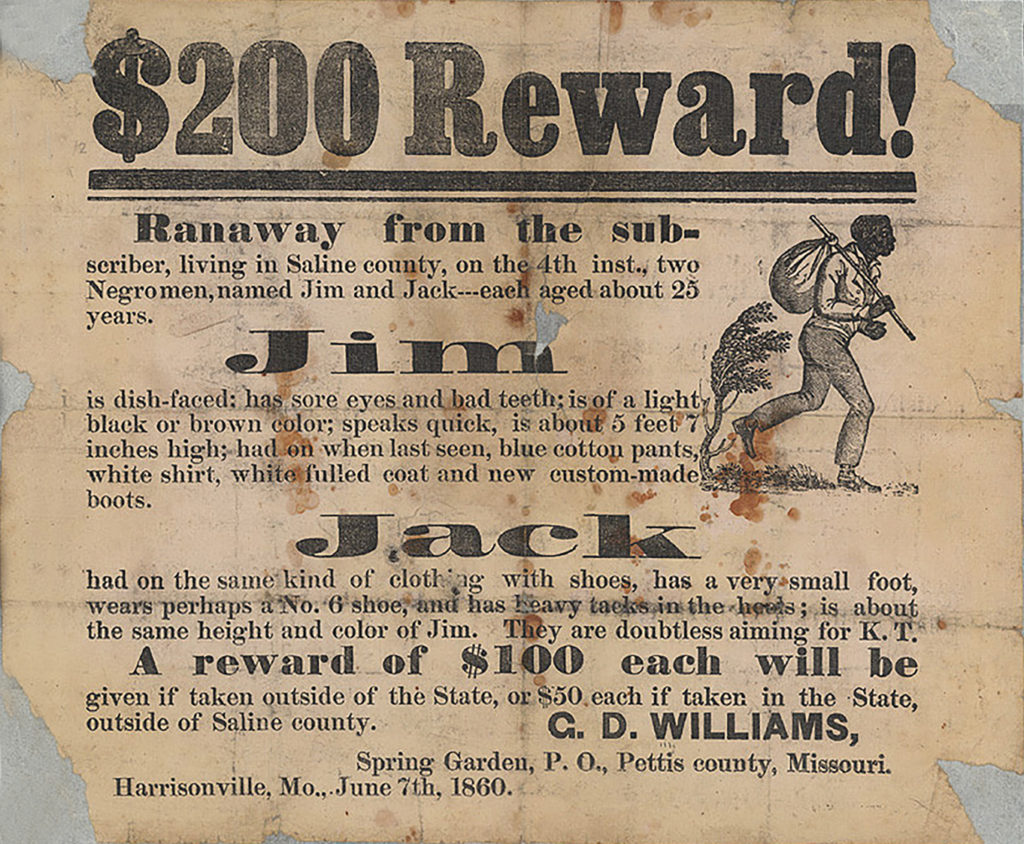

When the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed in 1854, 15 states (and three territories west of the Mississippi) still permitted slavery, while the abominable practice was illegal in 17 states and five territories.

With the handwriting on the wall regarding slavery’s ultimate survival, Southern states’ slave power block was desperate that Kansas become a slave state. Correspondingly, Northern anti-slavery forces, led by committed Abolitionists and anti-slavery activists, were equally determined that Kansas become free.

A Rush On Kansas

Frantically, residents of Kansas territory’s neighboring slave state, Missouri, fearful that a “free state” Kansas on its western border, combined with the established free states of Illinois on its eastern border and Iowa on its northern border, would surround the border slave state on three sides—becoming a runaway slave magnet—rushed “settlers” across Missouri’s western border into contiguous eastern Kansas to “vote-pack” Kansas into the Union as a slave state. Although the statewide population of Missouri was then split between pro- and anti-slavery adherents, the pro-slavery faction firmly held state power in Missouri’s capital, Jefferson City.

Adamantly opposed to slavery, the Boston-based Abolitionist, New England Emigrant Aid Company—generously financed by wealthy northeastern businessmen such as Eli Thayer, Alexander H. Bullock and Edward Everett Hale—quickly organized an anti-slavery settler movement. The Emigrant Aid Company funded the settlement of eastern Kansas, rapidly packing it with heavily recruited, anti-slavery settlers, and well-armed them with numerous Sharps .52-cal breech-loading rifles.

Both sides therefore—not just pro-slavery Missourians as is often claimed today—raced to populate Kansas territory with their ideological followers. Both sides unconscionably “packed” Kansas with adherents who obediently “stuffed” ballot boxes with votes to control the election. Anti- and pro-slavery adherents were equally guilty of vote tampering, voter intimidation, ballot-box stuffing and election malfeasance.

The stage was thus set for a bitter fight for Kansas’ statehood status: two well-armed opposing factions holding unwavering political positions faced off in what, according to the era’s terminology, was dubbed a “War to the Knife, and the Knife to the Hilt!” Yet the truth of the 1854-1860 “Bleeding Kansas” Border War is much different than what we accept today as “conventional wisdom.”

How Bloody was the Struggle?

Conventional wisdom only holds up until someone actually does the math. That someone is historian Dale Watts in his ground-breaking article “How Bloody Was Bleeding Kansas?” published in the Summer 1995 editionof Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains. Watts’ exhaustively-researched article discovered “Bleeding Kansas” produced only a small fraction of the politically-motivated deaths of anti- and pro-slavery forces both sides widely claimed.

Using historical documents and meticulously examining 1854-1860 death records, Watts determined which deaths were “political killings” (i.e., murders by a pro- or anti-slavery partisan because of the victim’s opposing political stance) or due to apolitical motivations (e.g., land disputes, personal animosity, or common criminality, robbery or homicides). Contemporary accounts nearly always overestimated the conflict’s deaths.

For example, the Hoogland Claims Commission 1859 report outlandishly claimed “the number of lives sacrificed in Kansas during [1854-1855] probably exceeded rather than fell short of two hundred.” However, Watts’s research verified the casualty record generally confirmed by Robert W. Richmond’s 1974 conclusion that “approximately fifty persons died violently [for political reasons] during [Kansas’] territorial period [1854-1860].”

Watts’s independent research revealed that of 157 documented violent deaths from 1854-1860 in Kansas territory, only 56 were attributed to the Kansas-Missouri political struggle. For historical comparison, Watts noted that in the contemporary “gold rush-era” California alone, a total of 583 people died violently in 1855, and at least 1,200 people were murdered in San Francisco between 1850 and 1853. This violent death comparison makes Kansas Territory seem almost calm given its small number of political killings recorded during the much-hyped Border War.

Single-digit Casualties

Significantly, Watts shows that of those 56 murders, 30 were “pro-slavery” advocates, including the only woman slain, Sarah Carver, whose husband merely professed to be pro-slavery while there were 24 anti-slavery proponents killed. One victim was an ostensibly neutral U.S. Army soldier while one was an officer whom both sides tried to claim. Moreover, some allegedly “bloody battles” (called “wars” and “massacres” at the time) were essentially bloodless or resulted in single-digit casualties. For example, in the June 1856 “Battle” of Black Jack not one person was killed.

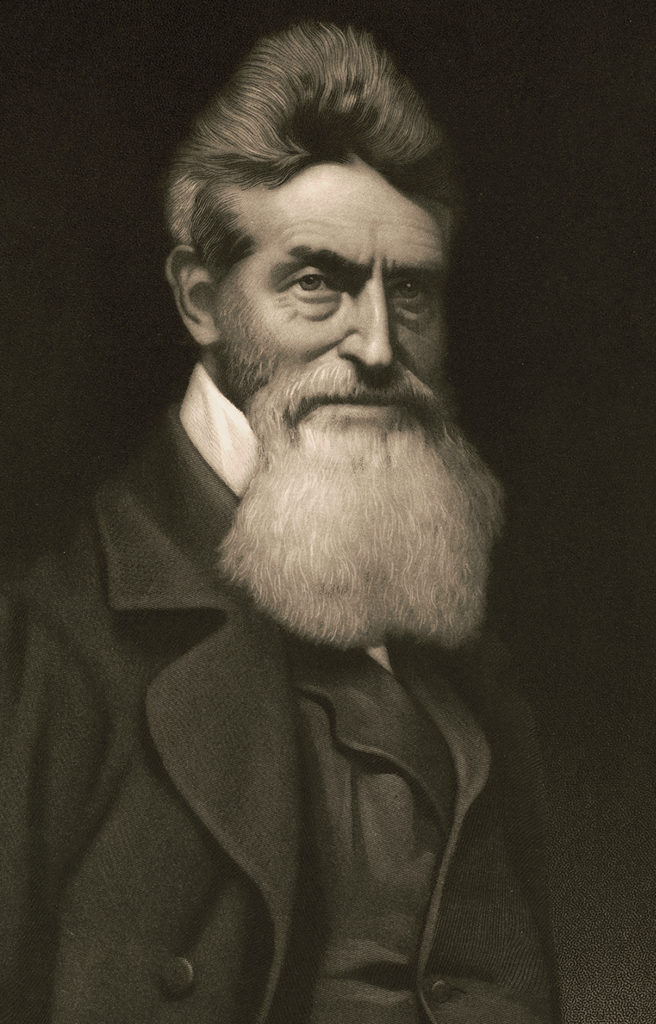

No “Bleeding Kansas” engagement produced more than five deaths. Anti-slavery radical John Brown and his sons killed five allegedly pro-slavery settlers during his notorious “Pottawatomie Massacre” from May 24-25, 1856 along Pottawatomie Creek. The attackers used broadswords to hack their neighbors to death in retaliation for the nearly bloodless “sack” of Lawrence three days prior.

Even the inaptly-named May 21, 1856 “Sack of Lawrence” produced only two casualties—one on each side. This incident is not to be confused with the later Lawrence Massacre during the Civil War in August 1863 by Confederate guerrilla William Quantrill’s raid that killed over 160, mostly civilians. The 1856 incident essentially consisted of Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones leading a force of about 800 citizens to Lawrence to enforce a legal warrant, and the damage to property consisted of the razing of the Free State Hotel (then used as headquarters of Kansas’ anti-slavery forces) along with the residence of anti-slavery firebrand, Massachusetts-born Charles L. Robinson who was elected Kansas’ first state governor in 1861 and in 1862 became the first U.S. state governor—and only Kansas governor—to be impeached. A single pro-slavery man was killed by being crushed in a collapsing building and a single anti-slavery man suffered a non-fatal injury.

Watts’s research proves conclusively that “Bleeding Kansas” was a myth that grew from fabrications in biased newspapers and fueled by political parties seeking to promote partisan interests. Nearly a million Americans would die making war on each other in the subsequent Civil War, which was in large part precipitated by the 1854-1860 “Bleeding Kansas” Border War.