In late 1862, Horace Washington and Olmsted Massy, former slaves from Virginia, met with a recruiting officer in New Orleans to join the 4th Louisiana Native Guards. The 4th was one of four infantry regiments formed as part of the Louisiana Militia in 1861 to protect New Orleans from Yankee invaders, its initial members free men of color pulled from the Crescent City itself. New Orleans’ capitulation to U.S. Navy Flag Officer David G. Farragut in April 1862, however, did not end the war for the free black soldiers of the 4th Native Guards or the other three regiments, who readily agreed to join the Union Army. After Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler assimilated the regiments into his military chain of command, recruitment was opened to former slaves, hence Washington’s and Massy’s desire to serve.

The two men were mustered in as corporals. At first, Butler used the Native Guard only to conduct guard duty in the vicinity. Eventually they were assigned to protect government facilities in Baton Rouge, but on May 27, 1863, the regiments joined Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’ troops in combat while storming the Confederates’ Mississippi River stronghold at Port Hudson, La. Though unsuccessful, the black troops proved their mettle in battle.

A week later, the Native Guard regiments were reorganized and given new designations. The 4th was now known as the 4th Regiment U.S. Infantry, Corps d’Afrique—assigned to the 19th Corps’ 1st Division in the Department of the Gulf. After the surrender of Port Hudson on July 9, 1863, the 4th was stationed there to guard captured stores but was soon ordered to garrison Forts Jackson and St. Philip below New Orleans. Duty at those riverside forts was pleasant, as civilians in small boats constantly stopped by to sell the soldiers fresh-picked oranges for a penny each. But on February 20, 1864, the unit was transferred back to Port Hudson.

Another new designation would come a few weeks later. Now known as the 76th United States Colored Infantry, under Colonel Charles W. Drew’s command, the regiment formally became part of the Union Army. That certainly produced a measure of pride for the men in the ranks.

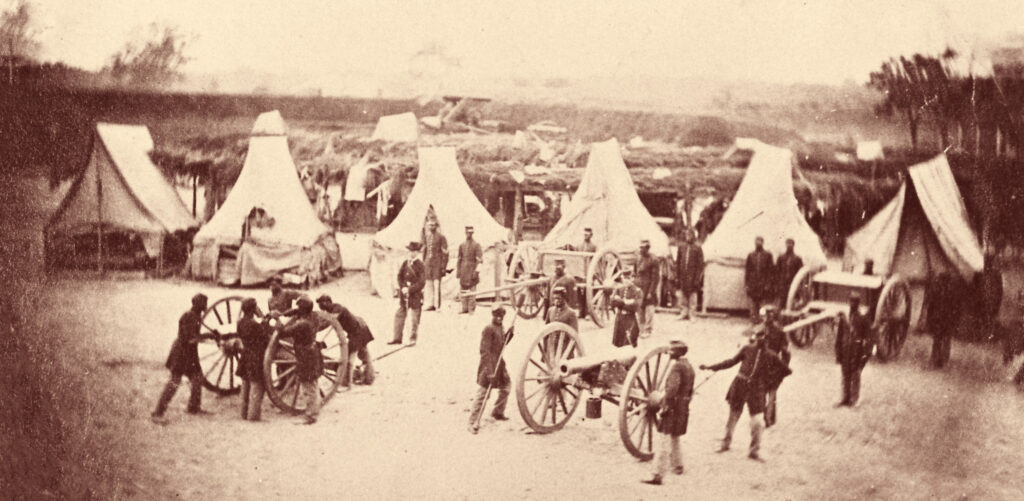

Besides guarding the smaller guns captured at Port Hudson, as the larger weapons had already been removed, the 76th was ordered to man them in case of attack by local Confederate cavalry units. Their post commander, Brig. Gen. John P. Hawkins, complained they were being stretched too thin, however. “There are 367 men in the regiment for duty,” he carped, “which barely supplies sentinels over the guns—the camp guard—with a few remaining for detachment drill at the pieces.”

In February 1865, the 76th served under Hawkins, now commanding a division of USCI troops at Algiers, La., near New Orleans. The 76th was put into the 3rd Brigade of Hawkins’ Division, alongside the 48th and 68th USCI. After a short stint, the 76th was transferred to Barrancas, Fla., temporarily becoming a part of the Federal District of West Florida.

Pensacola was its next destination—the port city in Florida’s panhandle serving as a jumping-off point to assist in the capture of Mobile. Major General E.R.S. Canby (Hawkins’ brother-in-law) assembled as many troops as he could to overtake the largest coastal city still in Confederate hands.

The boredom of constant inactivity in guarding facilities and cities was grating on the troops, who understandably wanted to see some action. At Mobile, their wishes would be granted. Following a few weeks of manning the trenches surrounding the city, the men were informed they were to participate in an upcoming assault on Fort Blakeley.

Wrote Drew:

On the night of April 1, my brigade [including the 76th, currently commanded by Major William E. Nye] was ordered to encamp in line of battle to the right of the Stockton road about two miles and a half from the enemy’s works, which was done in the following order: The Sixty-eight Regiment on the right, the Seventy-Sixth in the center, and the Forty-eighth on the left, the command occupying the advance and extreme right.

The next morning about 7:30 our pickets becoming warmly engaged, I formed line as quickly as possible, when I received an order to advance in line of battle. I immediately ordered two companies from each regiment deployed forward as skirmishers, and commenced the advance, which was continued for two miles through a thickly wooded and broken country, my skirmishers fighting about half the way.

Notwithstanding the numerous obstacles in the way, there was scarcely a break in the line the whole distance. The precision maintained by the line, as well as the bold and steady advance of the skirmishers under heavy fire, were sufficient, I think, to command the admiration of all. Arriving within half a mile of the works I received an order to halt, which was at once communicated to the skirmish line. Our position was then immediately in rear of a ravine about half a mile from the works of the enemy, my right resting on the swamp and my left connecting with General [William A.] Pile’s brigade….

Once halted, Drew’s units began construction of a fortification they named Battery Wilson. A battery of Union artillery moved in behind their position and began bombarding the Confederate position with their four 30-pounder Parrott guns. The artillery pieces later turned their attention to the Confederate gunboats Huntsville and Nashville coming up from Mobile Bay. The noise must have been deafening to the 76th and the rest of their brigade with cannon fire in front of and behind them.

On April 9, Drew noted:

I ordered the Sixty-eight and Seventy-Sixth Regiments (then in the trenches) to double their skirmish lines at 5 p.m. and drive the enemy from his rifle-pits, and if necessary to do it I should order out the regiments entire. Before the work was fairly commenced, however, I heard cheering on my left and saw the skirmishers of the First Brigade advancing. I immediately gave the command forward and forward the entire command (except the Forty-eighth Regiment left in reserve) swept with a yell….Before I could get up with the regiment they had fallen back to the abatis, and when the charge became general they, with the rest, went forward with a shout and did all that brave men could do. The result was soon accomplished and Blakely [sic] was ours. I cannot speak in terms of too much praise of the officers and men of my command. Each and every one did willingly all that was asked, working incessantly night and day a large portion of the time. The support and assistance rendered me by regimental commanders entitles them to my warmest gratitude. I could ask for none better.

“The loss suffered by my command from the investment of the place [Mobile] until its capture is 2 officers killed and 3 wounded; enlisted men, 12 killed and 65 wounded,” noted Major Nye.

The unit occupied Mobile for only a day before making a 12-day march to Montgomery, the Confederacy’s original capital. In June, they were directed to return to New Orleans. Major General Philip Sheridan then had them board steamers to Alexandria, La., to join forces that Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer was assembling for a mission in Texas.

Though not directly part of Custer’s cavalry division in Alexandria, the 76th and the 80th USCI would receive directives from the flamboyant general. Both regiments were to keep the peace in the town and guard governmental stores while Custer tried to train and have several Union cavalry units from different stations in the South work together as a cohesive group before departing for Texas.

Because of the exhaustive summer heat in central Louisiana, Custer had his troopers build brush arbors atop their canvas tents to lessen the sunlight beating down on them. The African American troops were ordered to occupy the cabins across the Red River in Pineville that had been erected by the Confederate forces occupying Forts Randolph and Buhlow in the winter of 1864-65.

“The men hastily constructed small cabins with pine boards [as well as chimneys for cooking],” recalled Confederate Major Winchester Hall. Noted Augustus V. Ball, a surgeon in McMahan’s Texas Battery, which occupied Pineville until their surrender on June 3, 1865, the structures were “roomy and spacious but they leaked badly and flooded frequently.”

Pineville was considerably smaller than Alexandria but was spared the burning of its counterpart town across the river by retreating Federal forces in mid-1864. The smaller town did not contain much to look at other than small businesses and the Mount Olivet Episcopal Church on Main Street. The large hog-processing building was vacant, an empty symbol of more prosperous times.

Though the works at the two forts were surrounded by massive walls, it wasn’t what the men hadn’t already seen at Port Hudson and Mobile. Something unique, however, was right there in the river in front of them. Being whisked away after only a day inside Mobile, the 76th did not have a chance to get a close look at the Confederate naval craft there. But moored in the river in front of the two forts was the infamous CSS Missouri. Tasked with guarding the ironclad that had struck fear in many Union naval commanders, the soldiers were able to get a closer look on a daily basis.

No major incidents with the civilian population in the area occurred on the 76th’s watch. The unit had more than 300 men present for duty and spent most of the time with repetitive drill, just like the Confederates in the vicinity had done when they were here earlier in the year.

In August the 76th would be sent to its final post: Greenwood, La., outside Shreveport. As their time there wound down, Olmsted Massy, now a sergeant, placed an advertisement in the Philadelphia-based Christian Recorder—attempting to locate his wife, Nancy, as he was ready to start a new life as a free man in New Orleans. “She was born and raised in Gochland County, Va.,” the advertisement read. “She was owned, about 15 years ago by John Mickey. Her name before marriage was Nancy Brown.”

The 76th officially disbanded on December 31, 1865.

Edward Windsor writes from Corinth, Miss.