On April 19, 1881, a raiding party of Lipan Apaches attacked John and Kate McLaurin’s ranch house in Frio Canyon in south-central Texas while John was away. They killed Kate and a teenage visitor named Allen Reiss but did not harm the three young McLaurin children. After stealing what they could, the raiders mounted up and fled south.

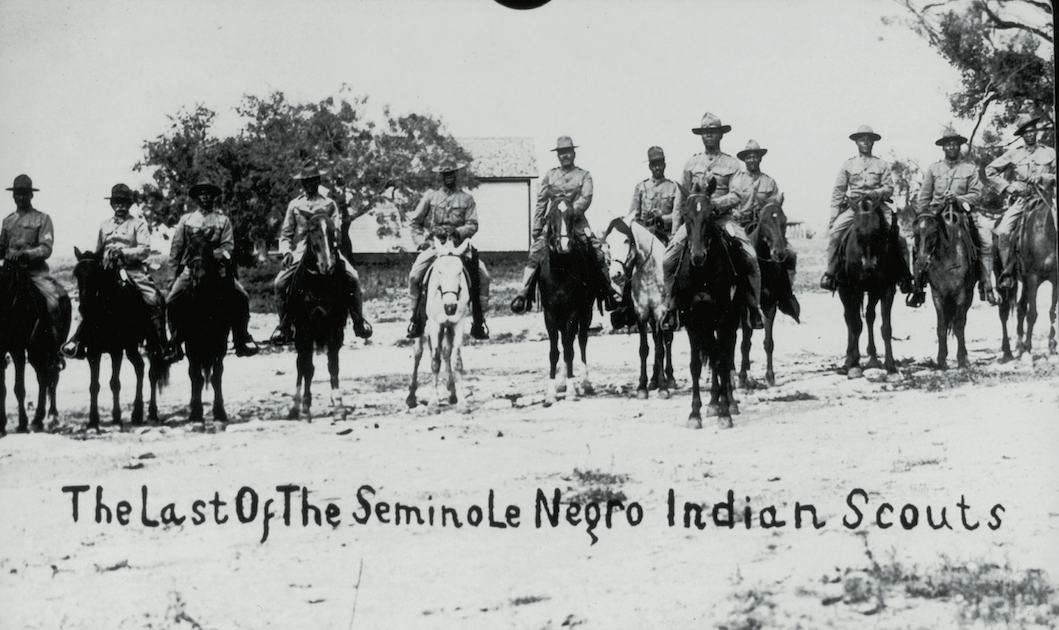

As word of the attack reached nearby Fort Clark, the post commander sent Lt. John Bullis and a troop of 35 black Seminole scouts in pursuit. Despite the raiders’ best efforts to obscure their trail, the scouts tracked them for six days over rocky and arroyo-laced ground across the Rio Grande into Mexico’s Sierra del Burro, where the Lipans, believing they had eluded any pursuers, had made camp.

Early on May 3, Bullis, after leaving seven men to guard the troop’s horses, surrounded the Lipan camp with his remaining men. At daybreak Bullis and the scouts rushed the camp and in the subsequent fight killed four of the raiders and captured an American Indian woman, a child and 21 horses. The Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts had suffered no casualties. Bullis, known as the “Whirlwind” or “Thunderbolt,” had struck again.

CHILDREN OF RUNAWAY SLAVES

Bullis had been commanding the scouts since 1873 and would do so until 1882. During that time he and his men would mount 26 expeditions, most lasting about two months, and participate in a dozen engagements. Bullis forged the scouts into what one modern historian termed “legendary fighters, trackers and horsemen.”

Composed of the descendants of runaway slaves who had been sheltered by Florida’s Seminole Indian tribes and had adopted their hunting, tracking and warfare practices, the scouts developed a reputation as one the toughest units in the U.S. Army. Their commander also earned a stellar reputation as one of the most successful American Indian fighters in American history.

John Lapham Bullis was born on April 17, 1841, on the banks of the Erie Canal in Macedon, N.Y., the eldest of seven children in the Quaker family of Dr. Abram R. and Lydia P. (Lapham) Bullis. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted as a private in tracked the enemy great distances, including one winter expedition in which Bullis and 39 scouts trailed Mescalero Apaches for more than a month, covering more than 1,260 miles of frigid desert while surviving on canned peaches and rattlesnake meat.

Since war’s end raiding parties striking into south Texas from below the Rio Grande had stolen tens of thousands of head of livestock, burned countless ranches and murdered scores of settlers. In all the attacks had incurred an estimated $48 million in property damage and livestock losses.

A MISSION TO DESTROY RAIDERS

In January 1873, with diplomatic efforts to control the raiders and seal off their Mexican sanctuaries at an impasse, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered Colonel Ranald D. Mackenzie and his 4th U.S. Cavalry to Fort Clark. That spring, in a personal meeting with Secretary of War William Belknap and Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, then head of the Military Division of the Missouri, Mackenzie was ordered to “destroy” the raiding American Indians, a message he interpreted to mean—as it did—that he was to enter Mexico after them.

For diplomatic reasons these orders were never put in writing or made official. The tide began to turn against the west Texas tribes when Mackenzie led six companies and a detachment of the Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts into Mexico against the Kickapoos and Lipan Apaches.

On May 17, 1873, once the scouts had pinpointed the Kickapoos, Mackenzie’s force of 360 enlisted men, 17 officers, two dozen black Seminole scouts under Bullis and 14 civilians rode out of Fort Clark headed for the Rio Grande. Just after sundown they crossed into Mexico. Following the scouts, the expedition kept steadily south, avoiding any settlements. By sunrise they had ridden 63 miles into Mexico and reached Río San Rodrigo upstream from three villages occupied by bands of Kickapoos, Lipans and Mescaleros.

After a short rest the cavalry charged the first village, routed its defenders and set the dwellings afire, before doing the same to the second and third villages. Mackenzie later reported the troopers had killed 19 American Indians and captured 40 women and children for only one man killed and two wounded. The troopers also rounded up 65 ponies and nabbed Costilietos, a senior chief of the Lipans.

Immediately after the raid the cavalry started for home, arriving back at the Rio Grande at dawn on May 19, having covered 140 miles in less than 50 hours. In exchange for the return of their captured wives and children, the Kickapoos agreed to return to the United States, and by the following year more than half the tribe had been resettled in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

RED RIVER WAR

In June 1874 the scouts again joined an expedition, this time in the Red River War against marauding Kiowas, Comanches, Southern Cheyennes and southern Arapahos. After several bloody incidents in Texas, Kansas and Indian Territory, the federal government was ready to strike back.

Following a strategy developed in late summer by Sheridan and General William T. Sherman, then commanding general of the U.S. Army, Mackenzie led eight companies of the 4th Cavalry, three companies of the 10th Infantry, one of the 11th Infantry and Bullis and his black Seminole scouts against Indians in the Texas Panhandle.

The column fought a skirmish in Tule Canyon on September 26, and two days later in a dawn raid swept down on a large group of Comanches, Kiowas and Cheyennes who had sought refuge in Palo Duro Canyon.

Although the troopers killed scarcely a dozen of their foe, they routed several hundred warriors, destroyed seven villages and captured nearly 2,000 Indian ponies, which they promptly slaughtered to keep from Indian hands. More important, the raid broke the back of the uprising, sealing the fate of the once powerful southern Plains tribes and paving the way for continued settlement of the Texas Panhandle. Bullis and his scouts had led the way.

MEDAL OF HONOR

It was during the 1874–75 Red River War that four of Bullis’ black Seminole scouts earned the Medal of Honor for actions illustrative of the courage and tenacity for which the unit was known.

In late September 1874 during a scout along the Red River tributary in Blanco Canyon, Pvt. Adam Paine (or Payne) and four other black Seminoles woke one morning to find themselves in the midst of several roving bands of Comanches. As they quickly mounted and sought to slip away, a group of seven Comanches spotted them and gave chase.

In the running fight that followed, Paine’s horse was shot from beneath him, leaving him to face the charging Indians alone. Using only his saddle for cover and showing remarkable coolness under fire, Paine shot the lead Comanche pursuer from his horse, which kept running toward the trooper.

Without skipping a beat, Paine was able to swing up onto the riderless mount and get away. All the scouts involved in the incident escaped with their lives, and a year later Paine received the Medal of Honor.

In mid-April 1875 Sgt. John Ward and Pvt. Pompey Factor—two of the original 10 scouts—and Trumpeter Isaac Payne were on patrol with Bullis when they came upon the trail of a herd of horses they suspected had been stolen from white settlers. Following the trail for eight days, on April 25 the four men finally spotted the horses in the custody of some 30 Comanches raiders seeking to cross the Pecos River near the site of present-day Langtry. Bullis and his scouts took cover in some rocks about 75 yards from the American Indians and opened fire.

In the ensuing 45-minute firefight the troopers killed three warriors, wounded a fourth and twice managed to wrest the horses from the Comanches. Finally recognizing that their opponents had flanked them, Bullis ordered his scouts to retreat. As they rode off, however, Ward looked back and saw Bullis was having trouble mounting his newly broken horse and was all but surrounded by Comanches.

Ward alerted the other two scouts, and the trio turned to rescue their commander. As Factor and Payne provided covering fire, Ward hauled up Bullis behind him on his own horse and galloped off, abandoning the commander’s frightened horse, saddle and all. All four escaped unharmed, though gunfire had shattered the stock of one of their carbines. Bullis recommended all three scouts for the Medal of Honor, which they received a month later.

While the expeditions of 1873–75 brought relative peace to the Texas frontier, things began to heat up again in the spring of 1876 when Lipan Apache raiders killed a dozen settlers. In retaliation the Army sent Lt. Col. William Rufus Shafter, Mackenzie’s successor at Fort Clark, after the Lipans with five cavalry companies. Bullis’ scouts again led the way across the Rio Grande.

Establishing his base camp near the mouth of the Pecos River, Shafter launched a series of probing raids deep into the Mexican state of Coahuila. For two years “Pecos Bill” kept up the raids, which despite Mexican protests pacified the border. Bullis’ scouts took part in fighting in the Devils River region of west Texas in the 1879-80 campaign against the Apache Victorio—a campaign that again spilled south of the border but largely ended the Indian wars of west Texas.

In fall 1879 Victorio, head of the Chihenne band of Chiricahuas, had fled the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona Territory with several hundred followers and for the next three years raided across the Southwest and into northern Mexico, pursued up north by Bullis’ black Seminole scouts and buffalo soldiers of the 9th and 10th Cavalry and to the south by Mexican troops.

DENIED RESERVATION RIGHTS

Finally, in October 1880 Mexican Colonel Joaquín Terrazas caught Victorio’s band in the Tres Castillo Mountains of Chihuahua south of El Paso. Only a handful of Indians escaped, and Victorio was not among them. The April 1881 raid on the McLaurin cabin is considered the last hostile American Indian action in south Texas, while Bullis’ counterattack in Mexico marked the last action fought against Indians by U.S. forces stationed in Texas.

In 1882, as the Army prepared to transfer Bullis to Indian Territory, grateful Texans filled the newspapers with words of praise, and the people of Kinney County awarded him two engraved ceremonial swords—one silver, the other gold—in appreciation of his efforts along the border. (Bullis’ daughters later donated the swords to the Witte Museum in San Antonio).

The scouts received no such acclaim. Considered black rather than Seminole, they were deprived of American Indian annuities and the right to reside on reservations, and by 1882 white citizens around Fort Clark wanted the scouts’ lands opened to public sale. The scouts and their families frequently relied on stray wild cattle for food, thus area whites viewed them as thieves.

In one instance Kinney County authorities billed the black Seminole community $40 for the deaths of four head of cattle. Bullis paid the fine.

In 1914 the Army formally disbanded the Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts and ordered the remaining black Seminoles and their families from the Fort Clark grounds. The forgotten scouts drifted into other occupations, and not until the 1920s were they able to acquire veteran’s benefits. In recent decades, however, the U.S. Army Special Forces paid tribute to the black Seminole scouts’ fighting reputation by adopting their crossed arrows insignia.

THE ‘WHIRLWIND’S’ LEGACY

Bullis continued to serve in the West as an American Indian agent and made several shrewd investments in land and mines that eventually brought him great wealth. But he remained in the Army. In September 1886 he served under Brig. Gen. Nelson A. Miles in the campaign that led to the surrender of the Chiricahua Apache Geronimo.

Bullis also served in Cuba during the Spanish-American War and in the Philippines during the subsequent insurrection before retiring in 1904 with the rank of brigadier general. General John Bullis died in San Antonio on May 26, 1911, and was buried at the San Antonio National Cemetery.

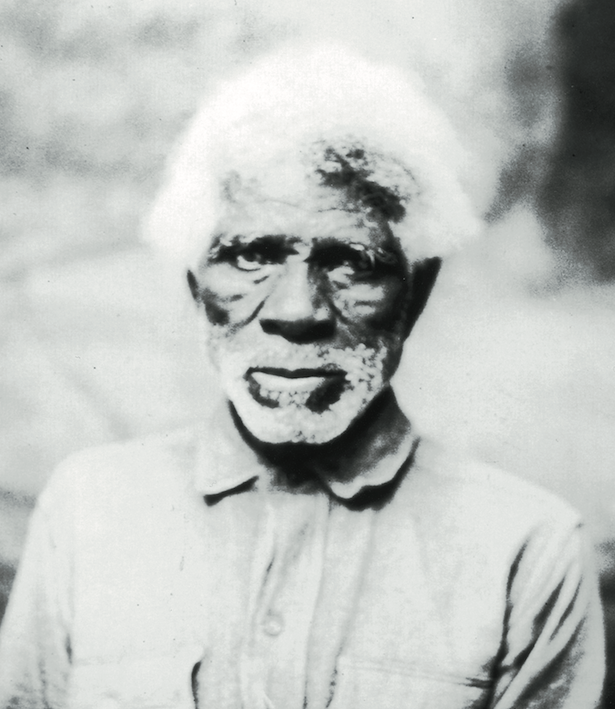

On hearing of the death, scout Sandy Fay stood vigil outside the general’s San Antonio house for a day and a night. Another former military comrade paid tribute to him in a letter: “I can think of no man who approached Bullis as a leader of men by pure and simple personality. We have only had one Bullis.”WW

Wild West contributor Chuck Lyons is a freelance writer from Rochester, N.Y.

By Chuck Lyons