Sometimes referred to as the “Forgotten War,” the War of 1812 officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent by delegates of the United States and Britain in Belgium on Christmas Eve 1814. News traveled slowly in the Age of Sail, however. The British commander in North America had yet to learn of the cessation of hostilities when he attacked American forces under Andrew Jackson in New Orleans in January 1815. Word of the peace agreement was even slower to reach the upper Mississippi Valley.

That spring the Missouri frontier was aflame as Sauk and Fox (Meskwaki) warriors from what are today Iowa and Illinois raided isolated settlements, killing soldiers and civilians alike. Although the fighting eventually ceased, the last battle of the war did not unfold in the salons of Europe or on the field at New Orleans. The final engagement pitted Missouri Rangers against British-allied Sauk warriors atop a pitted limestone bluff overlooking the Mississippi floodplain.

After the United States declared war against Britain on June 18, 1812, the federal government could not spare Regular troops for duty on the Missouri frontier. Thus Congress authorized the formation of Ranger companies to safeguard settlers. These were active-duty Volunteers, not militia called up during an emergency. The government recruited them primarily from French settlements within Missouri Territory. Rangers were responsible for providing their own horses, weapons, ammunition and rations, and were—in theory, anyway—to be reimbursed by the federal government.

When news of the brewing war reached the Missouri frontier, settlers began building forts for protection against British-allied Indians raiding down from the Great Lakes region. There were not nearly enough soldiers or militia to construct proper garrisons, so families pooled their resources to build settler forts. During the war they sheltered and slept within such fortifications, the men leaving only to farm crops and tend livestock.

Among the largest of the settler strongholds was Fort Howard, named for territorial Governor Benjamin Howard and sited just north of present-day Old Monroe, Mo. Built atop a rise on the floodplain west of the Mississippi, the fort was completed by settlers and Rangers over a few weeks in the summer of 1812. Commanded by Capt. Peter Craig, Fort Howard enclosed a half acre of land and housed the Rangers and 30-odd families. The stockade was 210 feet long by 105 feet wide, its long sides running north and south, with blockhouses on all but the southeast corner. Its residents lived in constant fear of Indian attack—especially in spring and early summer, when floodwaters enabled Indian canoes to reach high ground outside the fort. To access fresh water, the settlers dug a well within the stockade.

In 1813 the Rangers built nearby Fort Independence, on the west bank of the river across from a prominent sandstone formation known as Cap au Gris (just east of present-day Winfield, Mo.). The fort was also called Cap au Gris (Cape Gray), though gris was actually a misspelling of the French word grès (“sandstone”). While some families lived at Fort Independence, it was primarily a military installation, built to control traffic on the river and serve as a staging area for operations on the upper Mississippi. Fort Howard lay a few miles to the southwest, and a trail connected the outposts. In 1815 Capt.David Musick commanded Fort Independence.

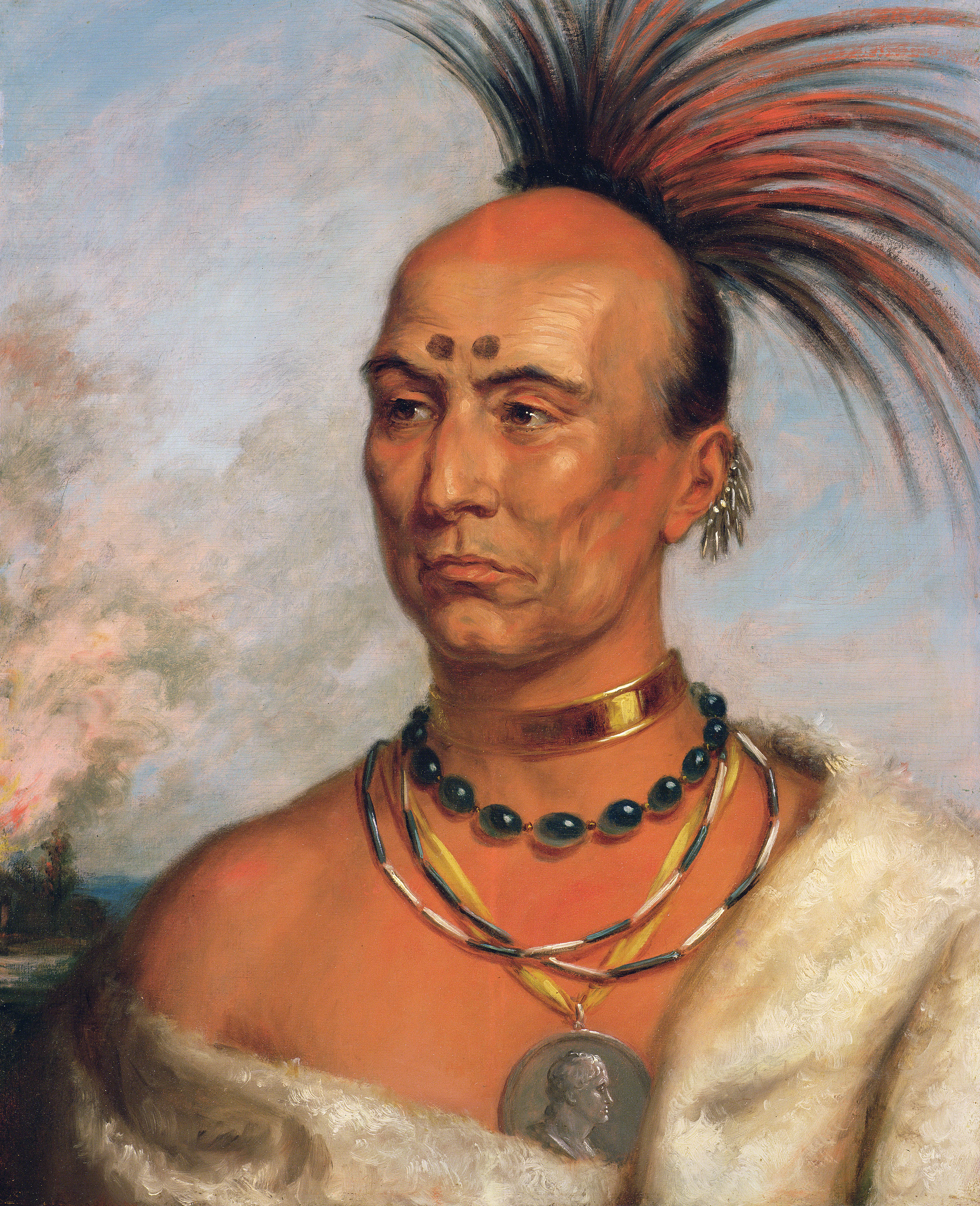

Leading the Sauk raids in Missouri that spring was Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (Be a Large Black Hawk), known to English speakers simply as Black Hawk. The 47-year-old war chief had led raids against Osages and settlers in Missouri since he was a teen. At the outset of the War of 1812 the Sauks and Foxes had allied with the British, battling U.S. forces along the upper Mississippi and attacking settlers on the Missouri frontier.

According to Black Hawk, after a friend’s son he’d adopted as his own was “cruelly and wantonly murdered by the whites” in the spring of 1815, he vowed revenge against settlers. Gathering warriors from Saukenuk, his home village and the Sauk capital (near present-day Rock Island, Ill.), he led the war party down the Mississippi in canoes, passing through deserted countryside. “We were pleased to see that the white people had retired from the country,” he recalled in his autobiography.

On the morning of May 24 he and another warrior paddled past Fort Independence, undetected in the predawn darkness, and beached their canoe on the west bank of the river.

Starting down the trail to Fort Howard, the pair encountered two men tandem riding a horse. The warriors fired their muskets, toppling settler Roswell Durgee to the ground. Bucked from the startled horse, the second man, noted Indian trader and scout Frederick Dixon, fled. Black Hawk gave pursuit, but on recognizing the scout, he resolved to let him live, as Dixon had helped the Sauks in better times. Meanwhile, Black Hawk’s companion scalped Durgee and left him for dead. After recovering his horse, Dixon tried to lead his suffering companion to Fort Howard. Durgee, however, was delirious and unable to walk, so Dixon abandoned him to his fate.

Black Hawk and his companion soon circled back and found Durgee alive. Black Hawk described the scene:

We met the man supposed to be killed coming up the road, staggering like a drunken man, all covered with blood! This was the most terrible sight I had ever seen. I told my comrade to kill him, to put him out of his misery! I could not look at him.

Durgee was not the first of Dixon’s traveling companions to have met with misfortune. In 1804 a Sauk war party led by Black Hawk killed three young sons of pioneer William McHugh as they rode with the scout a few miles north of the future site of Fort Howard. Dixon had managed to escape then, too.

About the time Black Hawk’s comrade was finishing off Durgee, the main body of the Sauk war party, some 30 strong, landed their canoes near the mouth of the Cuivre River, a few miles southeast of Fort Howard. Black Hawk and companion joined the warriors as they sloshed across the floodplain toward the fort.

Around noon the Sauk warriors reached the base of a limestone bluff overlooking the floodplain a quarter mile below Fort Howard. As they paused there amid the timber, a party of five Rangers paddled by in a canoe, bound for the fort. Capt. Craig had dispatched the men to retrieve a grindstone from settler Benjamin Allen’s deserted farm.

Springing from cover, the Sauks splashed through the shallows and attacked the Americans, shooting and tomahawking the men before they could react. The warriors killed three of the Rangers outright and mortally wounded a fourth. The fifth presumably escaped.

Hearing the shots, soldiers and settlers poured from the fort and opened fire on the warriors. The range was too great, however, and the Sauks fled up the bluff. Craig led about 40 Rangers through the shallows in pursuit, while some two dozen settlers circled around to cut off the warriors. The parties collided atop the bluff, and a vicious firefight erupted.

The warriors made a stand on what Ranger John Shaw later described as a mostly cleared field “about 40 rods [660 feet] across, beyond which was pretty thick timber.” The field was dotted with sinkholes—depressions caused by water flowing through limestone. Men on both sides sheltered behind the scattered trees for protection. “The loading was done quickly,” Shaw recalled, “and the shots rapidly exchanged.” In the initial exchange several Americans were killed or wounded. When a Ranger was hit, comrades sang out his name.

Unknown to either side, Capt. Musick and 20 Rangers from Fort Independence were only about a mile south of the bluff when the firefight started. Musick and his men were returning from a scout along the Cuivre, watering and grazing their horses, when they heard gunfire from the direction of Fort Howard.

The captain led his men to investigate. Their arrival startled the Sauks, who retreated north along the bluff. A dozen or so ran for the banks of Bob’s Creek, just north of the fort, while Black Hawk and some 20 others made for a large, brush-lined sinkhole. In the excitement Craig foolishly stepped into the clear and was shot dead for his trouble.

The Rangers quickly surrounded the sinkhole, which Shaw later described in detail:

The sinkhole was about 60 feet in length and from 12 to 15 feet in width and 10 or 12 feet deep. Near the bottom on the southeast side was a shelving rock, under which perhaps some 50 or 60 persons might have sheltered themselves. At the northeast end of the sinkhole the descent was quite gradual, the other end much more abrupt, and the southeast side almost perpendicular, and the other side about like the steep roof of a house.

Far from being a deathtrap, the sinkhole proved an excellent defensive position for the outnumbered warriors. To get a clear shot at the enemy, a Ranger had to crawl to the lip of the hollow and fire downward, exposing himself to Sauk fire in the process.

From their limestone lair the warriors dared their opponents to attack, while the Rangers did the same from above. Some Sauks sang death songs to the accompaniment of a makeshift drum of skin stretched over a hollow tree section. From time to time a warrior would crawl up to the lip of the sinkhole to fire at the Rangers, or a Ranger would crawl to the edge to fire down at the Sauks.

The stalemate had dragged on through late afternoon when Lt. Edward Spears proposed a means of approaching the Sauk position. “[He] suggested that a pair of cart wheels, axle and tongue, which were seen at Allen’s place, be obtained, and a moving battery constructed,” Shaw recalled. “The idea was entertained favorably, and an hour or more was consumed in its construction. Some oak floor puncheons, from 7 to 8 feet in length, were made fast to an axle in an upright position, and portholes made through them. Finally, the battery was ready for trial and was sufficiently large to protect some half dozen or more men.”

From the sinkhole the Sauks heard the sounds of chopping and hammering. Several curious braves finally crawled to the lip of the hollow and popped up for a glimpse.

About then the Rangers were pushing the completed battery forward. As the structure rolled toward the sinkhole, the Sauks noticed a flaw—an 18-inch gap between the ground and the wheeled end of the battery.

The Rangers had planned to fire at the Indians through the portholes in the planks, but the warriors fired up into the gap and at the portholes. One round struck Spears in the head, killing him, and other Rangers were wounded before they abandoned the battery.

Around nightfall the Rangers noticed more Indians moving toward Fort Howard. Hoping to draw attention away from their besieged comrades, the Sauks who had sought shelter in the brush along Bob’s Creek had emerged within yards of the undefended post and were firing in the air. Fearing for the families inside, Capt. Musick abandoned the fight at the sinkhole and had the men return to the fort with their dead and wounded—all but Spears, whose body was too close to the sinkhole to risk a recovery. In addition to Capt. Craig and Lt. Spears, five Rangers had been killed, three wounded. Three settlers lay dead.

Black Hawk and his men waited for nightfall before emerging from the sinkhole to join up with the other Sauks. Rather than make for the canoes through hostile countryside, Black Hawk decided they would return to Saukenuk on foot.

He also may have feared the prospect of paddling up the Mississippi against the current only to run the gauntlet at Cap au Gris, where Rangers from Fort Independence would likely be watching for them. Anyway, Black Hawk was satisfied with the results of the raid.

The settlers inside Fort Howard passed the night of May 24–25 in terror, realizing the spring floodwaters would allow Indian canoes access to the high ground. Shaw said the men stayed awake all night, their families “fearing they might not be permitted to behold another morning’s light.” There was no doctor at the outpost, so the able-bodied cared for the wounded as best as they could.

The next morning the Rangers returned to find the sinkhole abandoned. The Sauks had left behind five dead; beneath one lay Spears’ corpse, scalped and placed there for effect. Black Hawk admitted having lost only one warrior, but based on the amount of blood observed in the sinkhole, the Rangers speculated the Sauks had carried off most of their dead and wounded.

Musick and his men then returned to Fort Independence. The presumptive commander at Fort Howard, Lt. Drakeford Gray, had the dead buried and dispatched a runner to St. Charles, 14 miles southeast on the Missouri River, for medical aid.

That summer the representatives of 19 tribes met with U.S. commissioners in Portage des Sioux, 25 miles down the Mississippi from the battle site, and signed a treaty meant to assure peace on the Missouri frontier. Territorial Governor William Clark, of Corps of Discovery fame, presided over the negotiations. Black Hawk refused to attend. Not until the following year did he meet with Clark in St. Louis to sign his own treaty with the government. The venerable Sauk warrior refrained from taking up arms against the United States until the 1832 Black Hawk War, a conflict centered on the disputed terms of past treaties.

“The War of 1812 was a serious threat to the settlements along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers,” wrote Duane Meyer in The Heritage of Missouri. Yet with peace, thousands of Americans flocked to the territory. Settlement proved so rapid that Missouri achieved statehood only six years after the Battle of the Sinkhole. MH

Historian and retired Army officer Douglas L. Gifford specializes in American military history. For further reading he recommends Life of Black Hawk, by Black Hawk with John Barton Patterson; Tales of Black Hawk, the Red Head and Missouri Rangers, by Robert E. Parkin; and The Heritage of Missouri, by Duane Meyer.

This article appeared in the January 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: