Forgotten it seems in the continuing controversy over Confederate monuments is who put them up in the first place.

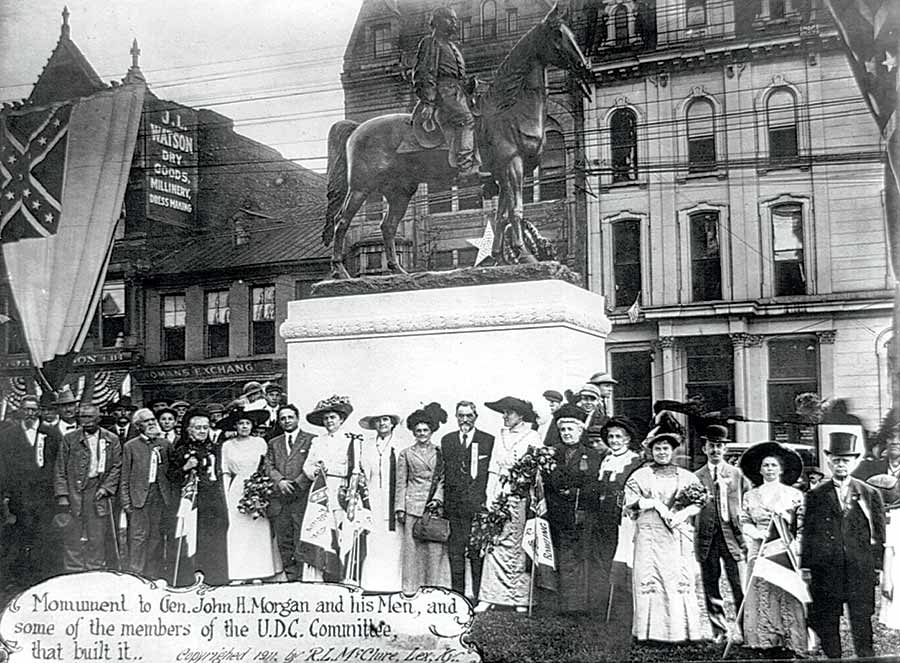

Ex-soldiers actually had little to do with placement of the now familiar marble and cast-iron representations of themselves in parks and courthouse squares across the South, or of the grand equestrian spectacles honoring their leaders. The statues didn’t appear in great numbers for more than 30 years after the war and were the product of a determined effort by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to champion the Lost Cause narrative that Southerners were not rebels or traitors but rather patriots defending states’ rights, as stated in the 10th Amendment. Slavery, they insisted, was a benevolent system, wherein slaveholders imparted Christianity to African “savages.”

Founded in 1894, the UDC was initially restricted to genteel women, mostly the offspring of officers, burning with resentment at how Northerners and historians had treated their fathers and mothers from Reconstruction to the turn of the century. More than anything, these women wanted to reclaim their defeated men’s lost honor.

An early objective of the UDC was the erection of monuments as tangible signs of pride and appreciation for elderly ex-soldiers while those men still lived. Monument building, though, was costly. A monument of a lone Confederate soldier, standing sentinel atop a pillar, was the least expensive and could be ordered from a catalog. But more elaborate monuments, like those in New Orleans or along Monument Avenue in Richmond, Va., were done by renowned, handsomely paid artists. In today’s currency the equivalent of millions of dollars were spent on building these memorials. And though the UDC was savvy at raising money, it also helped greatly that local and state governments often supplemented the funding. More than 700 monuments were erected across the South before World War II.

The end game, however, was vindication—recognition by Northerners that the South’s fight had been just and honorable. Members used considerable energy to squelch contradictory historiography and teach white children to honor Confederate heroes, and to be ardent believers in the Southern cause. Many monuments were placed where children would see them as they walked to school.

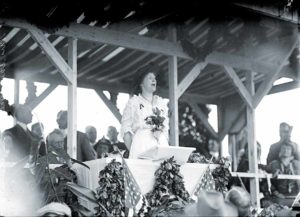

This push to maintain a world order of Anglo-Saxon supremacy was clear in monument dedication speeches across the South. For example, the ceremony for the 1907 unveiling of the Jefferson Davis memorial in New Orleans, attended by thousands, included over 500 children from the city’s white public schools—dressed in red, white, or blue and arrayed on a stand in the form of a Confederate battle flag, all singing classics such as “Dixie” and “America.”

About this time, the nation was gradually moving toward sectional reconciliation. It helped that Southern men had been well-represented in the U.S. Army during the 1898 Spanish-American War, but in the UDC’s view, exoneration of the Confederate generation must be total before the nation’s split could be fully healed.

In 1912, about 2,000 members traveled to Washington, D.C., for the UDC’s annual convention, the first time it had been held “outside the South” (if one doesn’t count the 1905 confab in San Francisco). President William Howard Taft was persuaded to address the delegates, and organizers lobbied successfully for a White House reception hosted by the president and first lady. Taft opened his address by noting the “patriotic sacrifice” of the Southern people and said bitterness over the war had dissipated to the point that reasonable Northerners could express “just pride” in Southern men and women. During a ceremony to lay the cornerstone for a monument to Confederate soldiers buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Democratic politician William Jennings Bryan served as the keynote speaker.

The 1914 unveiling of the Arlington monument was a critical moment in the fight for vindication. By allowing burial of Confederate soldiers at the sacred cemetery and accepting the monument to honor them, the federal government had fulfilled the Daughters’ conditions for reconciliation.

After World War I broke out in 1914, the UDC joined other organizations in calling on President Woodrow Wilson to keep the nation at peace. However, when the United States entered the war in 1917, the UDC became a dependable and enthusiastic participant. Praised for their contributions to the war effort and welcomed into partnerships with Northern volunteer groups, UDC leaders felt they had been able to vindicate the Confederate South “without sacrificing a single principle.”

Although the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s membership has dwindled, it remains a viable organization. Since the deadly violence in Charlottesville, Va., in August, several UDC–sponsored monuments have come down. Some chapter leaders were angry about the removals, but the national organization grieved in a statement that “certain hate groups have taken the Confederate flag and other symbols as their own” and denounced those who promoted “racial divisiveness or white supremacy.”

Despite the Daughters’ current efforts to distance themselves from hate groups, there is no denying the monuments were erected within a context of white supremacy. Given the unabating controversy, communities across the South will have to decide on their own whether to remove or keep the memorials intact.

Karen L. Cox is a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the author of Dixie’s Daughters (University Press of Florida, 2003).