HE SMOKED FOUR PACKS a day, drank a case of beer a day, read a book a day. He hobbled on a wooden leg—the result of a World War II wound—but loved to dance exuberantly. He refused to wear ties and preferred a cheap seat in the bleachers, even when he owned the stadium. He was baseball’s resident intellectual and most gleefully vulgar self-promoter. A cunning capitalist who owned three big-league teams, he voted for perennial Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas—even after Thomas died. “I’d rather vote for a dead man with class than two live bums,” he explained.

His name was Bill Veeck—Veeck As in Wreck, he titled his first memoir. In a second memoir, The Hustler’s Handbook, he offered a winking self-description: “A hustler travels by magic carpet and says (shouts, cries, coos), ‘Come fly with me.’”

Born in 1914, Veeck grew up in baseball. His father was president of the Chicago Cubs and Bill spent his childhood at Wrigley Field,

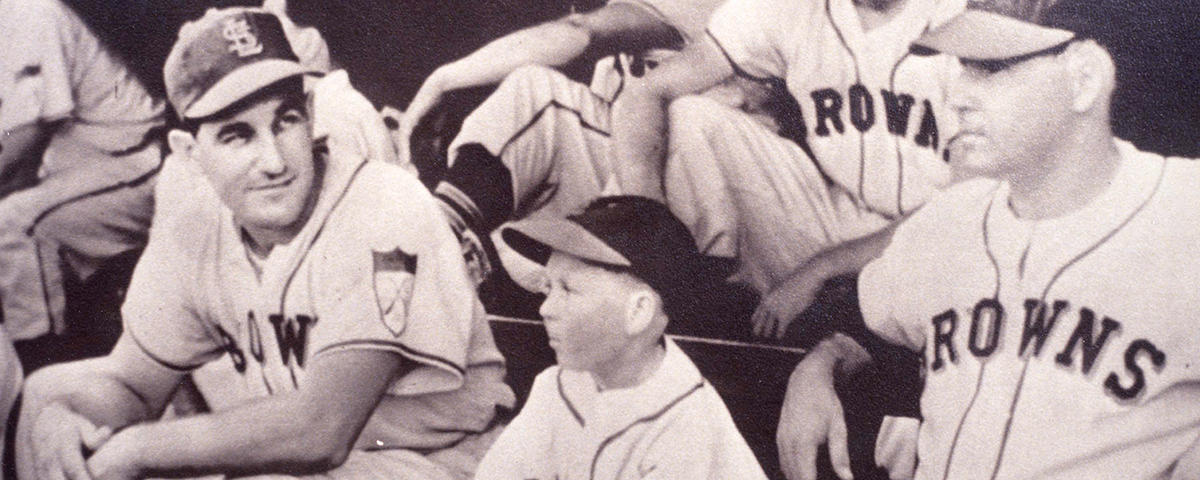

studying the game and the business. When Veeck senior died in 1933, the Cubs hired his son as an office boy. Seething with ideas—he designed the Wrigley scoreboard and suggested planting the now-famous ivy on the outfield wall—he was promoted to treasurer. But he wanted his own team and in 1941 he bought one—the bankrupt, last-place minor-league Milwaukee Brewers. He later owned the Cleveland Indians (1946-49), the St. Louis Browns (1951-53), and the Chicago White Sox (1959-61, 1975-80). He took two teams to the World Series but earned fame not for winning but for outrageous stunts. Sportswriters dubbed him “the Barnum of Baseball.”

Veeck put blackboards in stadium bathrooms to encourage graffiti. He presented umpires with bouquets of rotting vegetables while the PA system blared “Three Blind Mice.” To punctuate a doubleheader, he staged a full-blown circus—with acrobats, sword swallowers, and nine elephants. He invented the exploding scoreboard, which celebrated home-team home runs by detonating fireworks, blasting sirens, flashing strobe lights, and playing the “William Tell Overture.” He presented randomly chosen fans with surreal swag—a stepladder, a greased pig, a thousand silver dollars frozen into a block of ice—and watched onlookers laugh as the “lucky” winners struggled to haul the loot to their seats.

Veeck gave striking steelworkers free tickets. One Mother’s Day, he bestowed an orchid on any woman producing a picture of her kids. He staged special nights for cabbies, teachers, transit workers—so many that a wag named Joe Earley wrote a funny letter to a newspaper demanding “Joe Earley Night.” Veeck obliged, spotlighting Earley and presenting him with an “early American” house and an auto—a one-holer and a rattletrap Model T. Then he unveiled a brand-new Ford convertible as the crowd cheered.

Veeck’s most famous stunt promoted the St. Louis Browns, 1951’s most inept team. He hired 3’7”, 65-lb. Eddie Gaedel, dressed him in a uniform numbered “1/8” and sent him up to pinch-hit against the Tigers. Gaedel crouched, creating a cigarette-sized strike zone. He walked on four pitches and skipped to first, where a pinch runner took over. “I felt like Babe Ruth out there,” he said. The next day, major league baseball banned dwarfs while Veeck basked in publicity, telling reporters that while his tombstone would probably read, “He Sent a Midget Up to Bat,” he’d prefer “He Helped the Little Man.”

But Veeck was more than a shameless showman. In 1942—five years before Jackie Robinson integrated the majors by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers—Veeck, who thought a country fighting fascism would have to embrace equality, attempted to buy the struggling Philadelphia Phillies and staff the team with Negro League stars. “I’m going to put a whole black team on the field,” he said. He didn’t. Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis vetoed the deal.

In 1947, three months after Robinson’s debut as a Dodger, Veeck signed Larry Doby for his Cleveland Indians, integrating the American League. A year later, Veeck hired pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige, 42, legendary for his 21-year career on segregated teams and in Cuba. The Sporting News called that a cheap stunt: “If Paige were white, he would not have drawn a second thought from Veeck.”

“If Satch were white, he would have been in the majors 25 years ago,” Veeck fired back. He got the last laugh. Paige pitched brilliantly—and the Indians won the `48 World Series.

In 1959, Veeck went to the Series again, this time as owner of the White Sox, who lost to the Dodgers in six. Two years later, plagued by horrendous headaches, he sold the team. Doctors diagnosed a brain tumor. Veeck moved to Maryland’s Eastern Shore to spend his final days with his wife and kids.

But Veeck didn’t have a tumor. He recovered, read hundreds of books, wrote two memoirs, and designed the Maryland pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. In 1968, he took a job managing rundown Boston racetrack Suffolk Downs. Naturally, he brought the razzle-dazzle. He designed a tote board that flashed wild colors when a long shot won. He invented the Lady Godiva Stakes, featuring eight (clothed) female jockeys riding eight fillies. He bought prop vehicles from sword-&-sandals epic Ben Hur and put on a chariot race. He recounted his adventures in a third memoir whose title referred to manure management at the track—Thirty Tons a Day.

In 1975, Veeck bought the White Sox again, inviting fans to tear out the artificial turf so he could plant real grass. To cool off bleacher-ticket buyers, he installed a shower there. He often sat in nose-bleed seats himself. In 1979, a foolish stunt he hyped at Comiskey Park went horribly wrong. On “Disco Demolition Night,” between games of a doubleheader, an anti-disco deejay blew up a crate of disco records, whereupon thousands mobbed the field and rioted, setting fires and chanting “Disco sucks!”

In 1981, Veeck, 66, sold the Sox. Sick, his lungs ravaged from smoking, he somehow survived another five years, spending much of that time at Wrigley Field, watching the Cubs from bleachers he’d helped build nearly 50 years earlier. Shirtless in shorts, wooden leg exposed, he’d sip beer and shoot the breeze with fellow fans.

“This,” Bill Veeck said, “is the epitome of pleasure.”