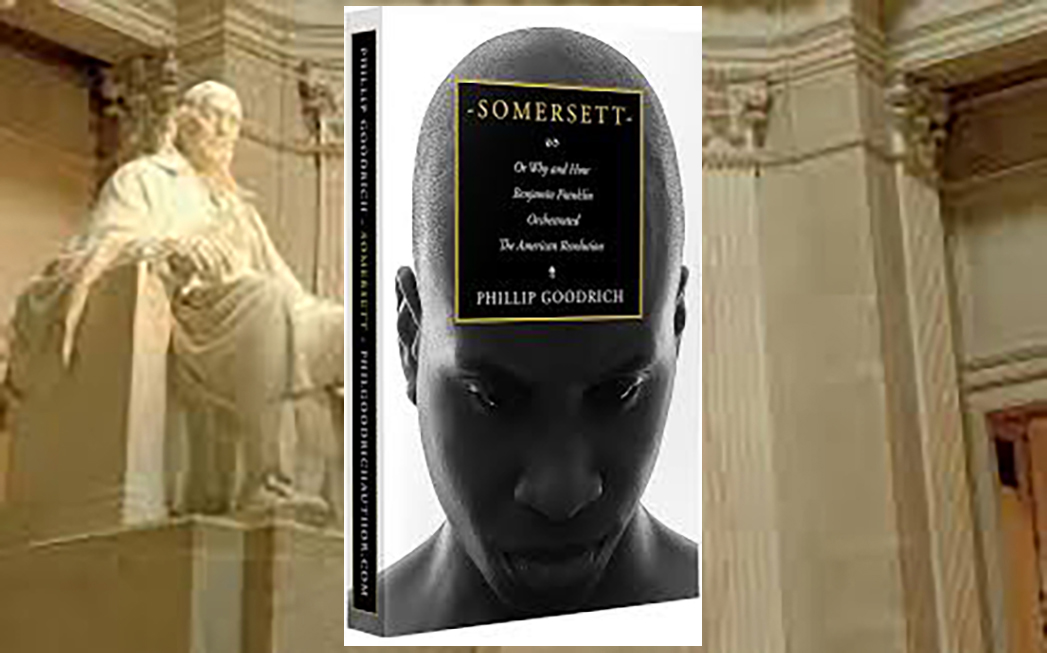

Somersett: Or Why and How Benjamin Franklin Orchestrated the American Revolution by Phillip Goodrich, philgoodrichauthor.com, 2020; $15.95

Diplomat, writer, scientist, and Founding Father Benjamin Franklin helped draft the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution, and signed both. So much has been written about him that you may wonder if there’s anything left to discover.

Enter Phillip Goodrich. The author—a practicing general surgeon and amateur history buff—takes readers deep into Franklin’s psyche and the intrigue leading to the American Revolution. His route runs from Franklin’s frenetic efforts to secure aid for Pennsylvania from its Penn family proprietors during the French and Indian War to his trip to London in 1757 to make additional appeals for that aid to pondering alternatives after losing his appeals and being humiliated when presenting colonists’ grievances.

Franklin’s inner circle of Thomas Pownall and Quakers Dr. John Fothergill and David Barclay, meeting regularly at Fothergill’s lodgings on Harpur Street, slowly face the inevitability and necessity of independence for the American colonies. “This requires,” says Franklin’s Scottish philosopher friend David Hume, replying to a hypothetical question posed by Franklin, “a single protagonist throughout the process to maintain that provocation.” Franklin reluctantly comes to realize he would have to be that protagonist.

But Franklin needs a catalyst—at least one legally manumitted, or freed, American or British slave—to ignite the simmering coals of unrest in the colonies. Such a catalyst presents himself on June 22, 1772, when British slave William Somersett, for whom the book is named, is freed by Lord Mansfield of the Court of Kings Bench, a case with ramifications on both sides of the Atlantic.

Franklin has prepared for this day and immediately sets his plan in motion with a coded editorial in The London Chronicle using Quaker pronouns to alert his Philadelphia Quaker friend Anthony Benezet, who forwards Franklin’s previously written provocative letters to John Hancock for mailing to colonial leaders. The die is cast.

Goodrich’s well-written, well-researched, somewhat folksy narrative history reads like a thriller. His thesis, that Franklin surreptitiously orchestrated the American Revolution, is well-developed. But he leaves us hanging, wondering why Somersett is so important, until half-way through the book.

Although the end is well-known—the colonies gain independence—there are enough twists and turns along the way to captivate historians and fiction lovers alike. Even those who think they know the details of Franklin’s life and the seeds of the Revolutionary War will learn something new in this book.

—Alice Watts contributes regularly.

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission. Thanks!