Desperate fighting south of Sharpsburg ultimately decided the Battle of Antietam

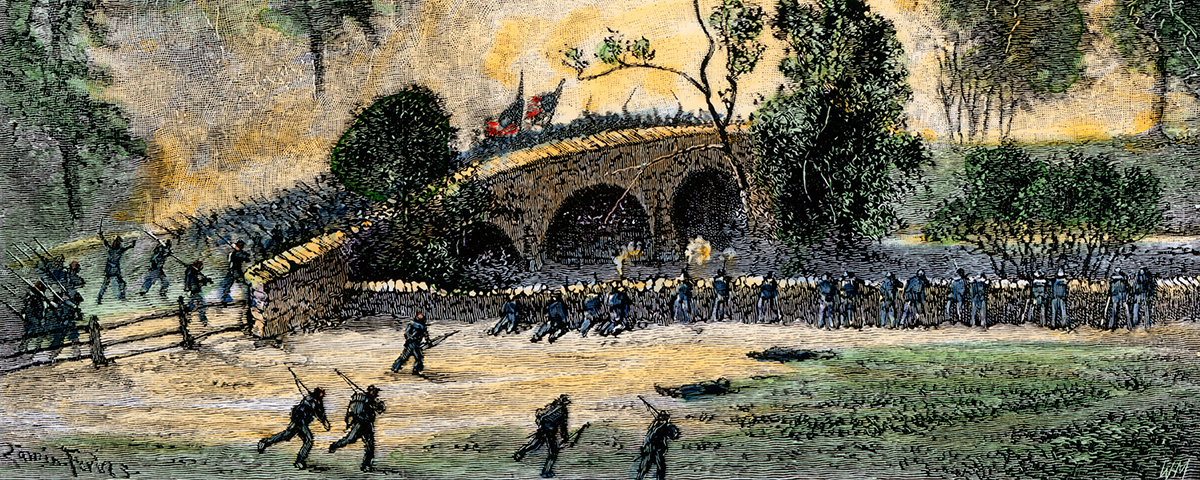

Accounts of the bloodiest one-day battle in American history—the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862—tend to focus on the morning and midday fighting in the northern areas of the battlefield: the attacks by Union troops under Joseph Hooker, Joseph K.F. Mansfield, and Edwin V. Sumner against Stonewall Jackson’s and James Longstreet’s corps, and the fierce struggles in the Cornfield, West Woods, and the Sunken Road. Yet the desperate and ultimately decisive fighting on the southern portion of the Antietam battlefield too often is either unfairly swept over with a few cursive sentences or ignored altogether, usually with dismissive conclusions such as “General A.P. Hill arrived late that afternoon and ensured the Confederates an opportunity to fight another day.” That hardly reflects what happened during some of the most brutal, bloody combat to take place the entire day. Although many historians’ accounts of the battle wrap up shortly after Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside finally makes his way across Antietam Creek on the bridge that will ultimately bear his name, plenty of critical fighting remained.

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]ntil late in the afternoon of September 17, 1862, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had fought to a stalemate around Sharpsburg, Md. The combat that day had unfolded generally from north of town to the south, with Federal attempts to break Lee’s strong defensive lines ending mostly with frustration. Even with superior numbers, McClellan was unable to get the best of Lee’s veterans.

The area over which the battle’s final attacks were made—the southern end of the battlefield—was much different than other areas because of the undulating terrain. The northern end of the battlefield, principally the land north of the Boonsboro Pike, is gently rolling. To the south, however, the terrain is very rough and broken. Deep ravines run through this section, and the main Confederate defensive line here at all points was perched 40–70 feet higher than the attacking Federal forces. The terrain south of the Boonsboro Pike played just as large a role in stopping the Union advance during the afternoon as did the Confederate defenders.

Entrusted to hold this section of the Rebel line was Brig. Gen. David R. Jones, whose division comprised brigades under Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett, Colonel Joseph Walker (Jenkins’ Brigade), Brig. Gen. Thomas Drayton, Brig. Gen. James Kemper, and Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs. Jones also had 28 pieces of artillery at his disposal. The northern end of his line rested on the Boonsboro Pike and ran southwest toward the Harpers Ferry Road.

Two of Jones’ brigades had already been in action: Toombs’ Georgians and a few dismounted South Carolina cavalrymen, numbering about 500 men. They were initially positioned above Burnside Bridge (known at the time as the Lower Bridge) as well as overlooking Snavely’s Ford, guarding these two crossings over the creek. Toombs’ men were forced to fall back from these positions after a staunch three-hour defense that began about 10 a.m. Garnett and his five Virginia regiments were located on the north end of Jones’ line, just south of the Boonsboro Pike. It was on this sector of the field that a small detachment of the Union 5th Corps—George Sykes’ Regulars—crossed the Middle Bridge at about 12:30 p.m. Garnett’s men were under constant fire from the long-range Union artillery east side of the creek, as well as the advancing infantry, but they held their ground unflinchingly until late in the day before finally being forced to abandon their position.

Lee’s use of his interior lines throughout the morning fighting was one of the keys to his successful defense, but it is significant that he shifted no infantry support to Jones at any point. The only help Jones eventually received came from A.P. Hill’s men, who arrived on the field after a roughly 15-mile march from Harpers Ferry. Earlier, however, the remaining 12 guns of Colonel Stephen D. Lee’s Battalion arrived as artillery reinforcements, having withdrawn under heavy Union artillery fire from the Dunker Church area. Colonel Lee’s guns were repositioned at about 3 p.m. on the high ground east of Sharpsburg, stretching across the Boonsboro Turnpike.

Two divisions spearheaded the advance to the south made by General Burnside’s 9th Corps. A third division was used to support the main assault. When the attack unfolded, it was 8,000 men strong, and the battle line was a daunting 1 mile long. On the north end of Burnside’s line was the division of Brig. Gen. Orlando Wilcox, who had two brigades under his command: Colonel Benjamin Christ’s on the right, Colonel Thomas Welsh’s on the left.

Burnside’s other division that assaulted the Confederate right was under the command of Brig. Gen. Isaac P. Rodman. It was his division that eventually gained the Confederate right flank, and it was also his division that was struck by Hill’s force as it arrived late in the afternoon. Under Rodman were the brigades of Colonels Harrison Fairchild and Edward Harland. Fairchild’s command consisted of the 9th, 89th, and 103rd New York Infantry. Three Connecticut regiments and one from Rhode Island made up Harland’s unit.

The division supporting Rodman’s main line was the Kanawha Division, commanded by Colonel Eliakim P. Scammon, with two brigades composed entirely of Ohio regiments. In addition to long-range Union artillery on the eastern side of Antietam Creek, two batteries lent close-in support to this advance. Positioned on a ridge between the Otto Farm Lane and the staging area of Fairchild’s brigade were batteries commanded by Captain Joseph Clark and Captain George Durell.

Rodman moved forward a little before 4:30 p.m. with about 2,000 men. Fairchild’s brigade numbered approximately 950 men, the 9th on the right, followed by the 103rd, and then the 89th. Leading Harland’s brigade was the 8th Connecticut, followed by the 16th Connecticut, and then the 4th Rhode Island. (The 11th Connecticut was not part of the advance because it had been engaged earlier at the Lower Bridge.)

The entire attack was made in echelon, beginning with Christ on the far right working southward toward Harland. As the long blue line advanced, the Confederate artillery—with command of the terrain—opened fire. Wrote Christ: “[A] battery on my left which commanded my whole line from left to right, [opened] and for thirty minutes we were under a most severe fire of round shot, shell, grape, and canister, and suffered severely.” Eventually Christ’s and Welsh’s brigades drove the Confederate defenders from their front westward into the streets of Sharpsburg.

Recalled Garnett: “I discovered that the Federals had turned our extreme right, which began to give way, and a number of Yankee flags appeared on the hill in rear of the town and not far from our only avenue of escape…the main street of the town was commanded by the Federal artillery. My troops, therefore, passed for the most part, to the north of the town along the cross-streets.”

After lying under devastating Confederate artillery fire for some time, Rodman observed Wilcox’s division moving on the right. At this point, he sent orders to his subordinates to begin their attack.

Fairchild’s brigade, moved through the Otto Farm Lane and down into numerous deep ravines. Its target was approximately 800 yards in front—a “bold elevation” crowned with a few pieces of Confederate artillery. Fairchild’s men also had to cross a plowed field, as well as at least five separate fence lines. In addition, the 89th New York, on the brigade’s left, had to advance through what was known as the “Lower” or “Forty Acre Cornfield”.

Throughout this advance, the brigade commander used the deep swales to halt and dress his ranks before cresting the next ridge in view of the Confederate artillery to his front. A thin skirmish line pestered the Union soldiers as they advanced, but at this point it was still the artillery doing most of the damage to the New Yorkers.

Waiting atop steep embankments, just out of view of the attacking Federals, were Kemper and Drayton’s Confederate brigades, totaling about 590 men. Shortly before Fairchild’s men reached the “bold elevation,” the Confederates were thrown to the crest of the ridge, Drayton behind a stone wall and Kemper using protection offered by a stout rail fence. At this point, the Rebel batteries of Captains J.S. Brown and James Reilly began moving back toward the town.

As Fairchild’s New Yorkers crested the hill at the double quick, they came under devastating fire from the Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia troops. The 9th New York felt the brunt of this fire and its colors went down, only to be picked up and borne aloft for a few short seconds before being knocked down again and again. Eventually Lieutenant Sebastian Meyers and Captain Lawrence Leahy each picked up a blood-stained banner and encouraged the 9th to press forward. Every man who could continue sprang to his feet and charged the stone fence protecting Drayton’s men. A sharp hand-to-hand struggle ensued in which the defenders were driven from their position. The 9th New York, which now numbered about 100 men, was halted and rallied by Lt. Col. Edgar Kimball.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]o the south of this struggle, the 89th New York was also having success. As the regiment crested the ridge, a volley delivered by the 17th Virginia, Kemper’s Brigade, cut a tremendous swath through their line. The New Yorkers staggered, but returned fire and stood their ground. The six-rail fence the Virginians were behind helped to absorb many of the Yankee bullets sent their way, but it was only a matter of time before the small band was driven from the field. Colonel Montgomery Corse of the 17th Virginia wrote of the uneven fight: “We put into the fight but 46 enlisted men and 9 officers…7 officers and 24 men were killed and wounded and 10 taken prisoners.”

This engagement continued for about 10 minutes before the Confederates were driven into the south end of Sharpsburg. For lack of support, the 9th New York and 89th New York were soon forced to fall back.

The 103rd New York did not advance past the crest of the ridge. The rough terrain and the Confederate artillery had reduced the regiment to a skeleton squad. By the end of the day, Fairchild’s brigade had suffered more casualties than any other Union brigade in the battle in a little more than a half-hour of fighting—455 of 940 killed, wounded, or missing (48 percent).

As the attack by Harland’s brigade, advancing to the south of Fairchild, got under way, a series of events prevented it from lending any strength to Rodman’s advance. Stated Harland in his after-action report:

When the order was given by Gen. Rodman to advance, [it] started promptly. The Sixteenth Connecticut and the Fourth Rhode Island, both of which regiments were in a cornfield, apparently did not hear my order….This delay on the left placed the Eighth…considerably in the advance of the rest of the brigade.

The 16th Connecticut and the 4th Rhode Island were in the Forty Acre Cornfield and, to make matters worse, it was the 16th’s first battle. The complications of attempting to maneuver a regiment in a tall cornfield over uneven terrain was a daunting task, but as this regiment had had no military training until late August, it proved nearly impossible for its colonel, Francis Beach.

The 16th prepared to go into battle behind the ridge where Clark and Durell’s batteries were positioned and came under galling artillery fire. While the 8th continued to advance, the other two regiments floundered in the cornfield. Harland, riding with the 8th, asked Rodman if he

should go back and bring the other regiments forward. “[Rodman] ordered me to advance the Eighth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers,” Harland wrote, “and he would hurry up the Sixteenth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers and the Fourth Rhode Island volunteers.” A gap of more than 600 yards opened between the 8th and the 16th. It was through this gap that the Confederate reinforcements under A.P. Hill pounced.

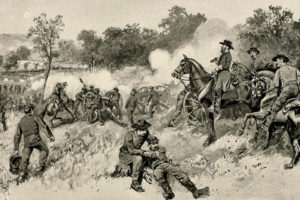

The 8th Connecticut encountered many of the same terrain problems as Fairchild’s men and also came under fire from the Pee Dee Artillery, commanded by Captain David McIntosh—one of the first units of Hill’s Division to arrive from Harpers Ferry. Despite taking significant casualties, the 8th pressed on. As the regiment crested the ridge, which by this point had been vacated by the 9th and 89th New York, now moving in the direction of Sharpsburg, one company saw an opportunity to move toward McIntosh. Hill’s main body, however, had arrived on the field. The general had placed his men along Miller’s Saw Mill Road in perfect position to strike the exposed Federal far left flank. Letting loose the feared “Rebel Yell,” Brig. Gen. Lawrence O’Bryan Branch’s North Carolinians moved directly at the 8th Connecticut.

With Branch’s attack under way, another of Hill’s brigades, commanded by Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg, struck the end of the Union line in the Forty Acre Cornfield. Turns out the 16th Connecticut was in perhaps the worst spot on the field. It had advanced across the Otto Farm Lane into the northeast part of the cornfield and then to the bottom of a ravine. From this spot, visibility was extremely poor, due to the tall corn and the sharply rising terrain. Shortly after arriving in this position, Colonel Beach sent out skirmishers, who advanced to the edge of the high ground near the southwest corner. The 16th was at this point moving in almost the opposite direction of the 8th because of the confusion created by the terrain and the tall corn.

Rodman, on high ground with the 8th, was able to view Gregg’s Brigade preparing to move into the cornfield, and could see his division was in danger of being flanked. Shortly after he sent word to Beach to swing his men to the left to meet the attack, Rodman was wounded. Though with restricted visibility, Beach’s inexperienced unit eventually completed the difficult maneuver.

The 1st and 12th South Carolina, both part of Gregg’s command, moved into the southwest edge of the cornfield. They drove back a skirmish line sent forward by Beach and continued to move deeper into the corn. The South Carolinians were forced to halt momentarily, and then the 12th, under Colonel Dixon Barnes, charged down into the ravine upon the Connecticut troops’ position. The 16th’s green soldiers were able to fire in response and repulsed the 12th’s charge, without assistance from the 4th Rhode Island, which had just moved in on the 16th’s left. For a few short minutes, it appeared this southern anchor of the Union line would hold.

Confederate Brigadier General Maxcy Gregg was surveying the field with some staff officers during a lull in the action when he was struck in the hip by a bullet. While awaiting the arrival of the stretcher bearers, he began to delegate messages and orders to his staff officers. Upon their arrival and further investigation by the medics, Gregg was informed that the bullet did not penetrate his skin. Relieved and with renewed vigor, he promptly returned to the saddle and rode off. The next morning at breakfast, Gregg pulled out his handkerchief and while in the process of unfolding it a deformed bullet dropped to the ground. Gregg survived with only a bruise. –Brian Baracz

Confederate Brigadier General Maxcy Gregg was surveying the field with some staff officers during a lull in the action when he was struck in the hip by a bullet. While awaiting the arrival of the stretcher bearers, he began to delegate messages and orders to his staff officers. Upon their arrival and further investigation by the medics, Gregg was informed that the bullet did not penetrate his skin. Relieved and with renewed vigor, he promptly returned to the saddle and rode off. The next morning at breakfast, Gregg pulled out his handkerchief and while in the process of unfolding it a deformed bullet dropped to the ground. Gregg survived with only a bruise. –Brian Baracz

After firing a few volleys, the 4th Rhode Island was ordered to cease fire for fear it was targeting Union soldiers across its front. But those “Union soldiers” turned out to be Confederates of the 1st South Carolina (Provisional Army), lending support. which had moved in on the right of the 12th to lend support. Yet the 1st was on the verge of running out of ammunition and started to fall back through the cornfield when the final element of Gregg’s Brigade, the 1st South Carolina Rifles, moved forward on the 4th Rhode Island’s flank.

The thin line of men from Connecticut was charged again by the 12th South Carolina, forcing them and the Rhode Islanders to retreat. What had been the Union anchor was no more.

Meanwhile, higher on the ridge near the Harpers Ferry Road, more of Hill’s reinforcements moved onto the field. Confederate Colonel James H. Lane, who took command of the brigade after Branch was killed later in the fighting, wrote in his after-action report: “[T]he brigade moved nearly at right angles…on the enemy’s flank.” The enemy flank was the 8th Connecticut’s, just on the other side of a narrow cornfield. When the 37th and 7th North Carolina, part of Branch’s Brigade, burst out of the cornfield, they were suddenly less than 150 yards away. Those two regiments’ fire, combined with that of McIntosh’s guns and the remnants of Jones’ Division on the Harpers Ferry Road, forced the 8th Connecticut to fall back. The 8th had lost almost half of its unit attempting to turn the Confederate flank: 34 killed and 139 wounded.

By this time, Rodman’s division was retreating back toward Antietam Creek. Farther to the north, the ground gained by Wilcox’s division was also relinquished because the Union left had crumbled; therefore, any attempt to move toward the Confederate line would expose the Union left even further to a Confederate flank attack.

The Kanawha Division was sent forward to lend support. On the right, Crook’s brigade (the 11th, 28th, and 36th Ohio) advanced, but halted in the vicinity of the Otto House. Meanwhile, on the opposite end of Rodman’s once-solid line, Ewing’s brigade (consisting of the 12th, 23rd, and 30th Ohio) was thrown forward.

As the 23rd and 30th Ohio advanced, the 12th remained back on the ridge that Clark and Durell’s batteries had earlier occupied. The 30th halted in the northwest corner of the Forty Acre Cornfield, facing west behind a stone wall, with the 23rd behind the same stone wall, on the 30th’s right.

As soon as the Ohioans reached the wall, they attempted to cover the 8th Connecticut’s retreat by firing at the flank of the 7th and 37th North Carolina, forcing those regiments to move west toward the Harpers Ferry Road. That diversion lasted for only a short period. Hill’s final brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. James J. Archer, soon crested the ridge on the Harpers Ferry Road and deployed into a battle line. Although Archer was extremely ill and had ridden to the battlefield in an ambulance, he gathered enough strength to lead his men into the fight—though fewer that 400 were available by the time he reached the field.

Archer deployed skirmishers and then, after some confusion, advanced his main line eastward through a narrow field of corn, adjacent to the Harpers Ferry Road. The brigade, accompanied by some of Toombs’ men, then charged 300 yards downhill to attack the stone wall protecting the 23rd and 30th Ohio. Subsequent attacks by the 7th and 37th North Carolinas as well as Gregg’s pesky South Carolinians had the Ohioans all but surrounded. The Federal regiments somehow got away and made their way through the Forty Acre Cornfield. A tattered group of Ohio and Connecticut soldiers made a brief stand, but that was all.

Commanders from both sides attempted to shore up their weak and weary lines. Branch repositioned his brigade behind Archer’s along the stone wall bordering the Forty Acre Cornfield and then rode in the direction of the 12th South Carolina. As he raised his field glasses to inspect the Union line, a bullet crashed through the glasses, killing him instantly.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Union advance on the southern end of the field tends to get overlooked, but clearly the Battle of Antietam did not end with the engagement at Burnside Bridge. Tellingly, it was neither the Irish Brigade nor the Iron Brigade that sustained the highest Union brigade casualty rate in the battle. Rather, it was Harrison Fairchild’s New Yorkers who fought on this southern area of the battlefield.

Until the early 2000s, a large land tract on the southern end of Antietam National Battlefield was privately owned. The only way to view this section of the field was by driving along the auto tour route. But in July 2003, a deal between a local family and the National Park Service added more than 140 acres to this section of the battlefield. This acquisition added the land over which Rodman’s division attacked on the late afternoon of the battle, and now this unfairly neglected area of the Antietam battlefield can be studied “up close” by Civil War students and historians. –Brian Baracz

Brian Baracz, a first-time contributor to America’s Civil War, has been a Park Ranger at Antietam National Battlefield in Sharpsburg, Md., since 2000. Among his previously published work are articles on Civil War Generals George S. Greene and Bradley T. Johnson.