In a war known for its provocative personalities, few could compete with Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler. An established antebellum politician, lawyer, and businessman, he gained fame during the conflict as one of the first Union generals who refused to return escaped slaves to their owners in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act. He was also notorious for defending his opinions with an acidic tongue—a habit that once led Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor to observe dryly, “in the war of epithets [Butler] has proved his ability to hold his ground against all comers as did Count Robert of Paris with sword and lance.”

Like Butler, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard had a provocative personality and a mixed record of success. Blessed with considerable dash, charisma, but also arrogance, the Creole commander from New Orleans had been a Southern hero early in the war, for his success at forcing the surrender of Fort Sumter and then victory at the First Battle of Manassas. Despite a series of setbacks in 1862, Beauregard’s resilient defense of Charleston in 1863 had restored his reputation, though his relationship with Confederate President Jefferson Davis had become almost irrevocably icy by the spring of 1864.

By fate, Butler and Beauregard found themselves at the head of opposing armies on the Virginia Peninsula in 1864: Butler in command of the Army of the James, Beauregard the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia.

Their showdown in the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, lasting May 5 through June 7, 1864, remains one of the war’s most overlooked military ventures. It should not be relegated to sideshow status, however. That spring, Butler’s army was handed the critical role as “Left Hook” in Ulysses Grant’s massive three-pronged advance on Richmond, and even though Butler seemed to have the parts in place to succeed, he was instead left to rue lost opportunities and to cast blame on his subordinates.

Although there had been missed Confederate openings too, one thing was certain by June 7: Beauregard had managed to turn back Butler’s onslaught and Grant had been stopped on the outskirts of Richmond. He would not claim the coveted Confederate capital for another 10 months.

Plans Afoot

On March 2, 1864, newly minted Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was named general-in-chief of the Union Army, tasked with defeating General Robert E. Lee in the field and, in so doing, finally bringing the destructive war to an end. The campaign Grant began planning that spring would be the largest and most complicated of the entire war. A force of nearly 180,000 men—the bulk in Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac—would advance on the Confederate capital of Richmond in four columns.

Still largely untested as a field commander, Butler met with Grant in Norfolk on April 1 to discuss the upcoming offensive. While the Army of the Potomac advanced through central Virginia and Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel followed suit in the Shenandoah Valley, Butler’s army was to proceed north along the James River, tying up forces that might otherwise aid Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

With roughly 40,000 men, the Army of the James featured a mixture of new recruits, battle-tested regiments, and garrison regulars, as well as seven regiments of highly motivated yet inexperienced United States Colored Troops.

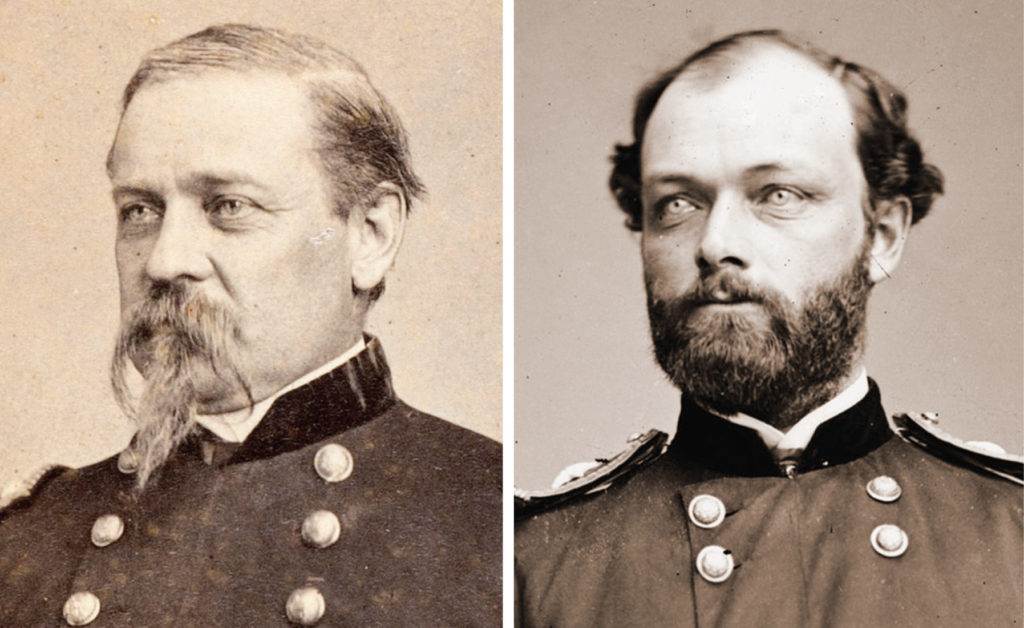

The exact credentials of Butler’s commanders were disputable, principally Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith of the 18th Corps and Maj. Gen. Quincy Adams Gillmore of the 10th Corps. Though popular with his men, Smith was known for being hypercritical of his superiors, and in 1863 he had been sidelined because of his personal attacks on Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. His good service under Grant at Chattanooga, however, had allowed him a return to prominence. Grant, in fact, permitted Smith to send him reports, an indication that Butler did not have the general-in-chief’s complete trust.

Butler also had the services of Rear Adm. Samuel P. Lee’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which included 41 warships and six ironclads. In the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, Lee’s squadron would be involved in the largest single amphibious landing of troops to take place the entire conflict.

As Butler amassed his forces, the Confederate government in Richmond took note and began looking for a commander to fashion an able response. At General Braxton Bragg and Lee’s behest, President Davis hesitantly turned to P.G.T. Beauregard. The command Beauregard received was scattered, and he endured an early setback when an attack at New Bern, N.C., by Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke was called off prematurely.

Butler began moving on May 4, with Brig. Gen. Edward Hinks’ USCT regiments quickly taking several positions along the James. The main landing, though, came May 5 at the historic port town of Bermuda Hundred, located near the confluence of the James and Appomattox rivers. “No opposition thus far,” Butler would report to Grant: “Apparently a complete surprise.”

That it was a surprise was a bit of a stretch, but Brig. Gen. George Pickett’s command in Petersburg had been left relatively isolated. He was instructed to hold out as reinforcements were rushed to Virginia.

After the war, Butler contended he had wanted to attack Richmond that night, having been told by a spy that the capital was nearly defenseless. He claimed that Gillmore and Smith overruled his plan, and that one of them had flatly refused to carry out such an order. That was unlikely. Butler, for example, was not known for being aggressive, and Smith and Gillmore were rarely so blunt when dealing with their superior officer.

On May 6, Butler took up advanced positions and kept most of his men digging entrenchments to protect his base of operations. Only a few brigades ventured out to raid the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad, and Brig. Gen. Charles A. Heckman’s 2,700 man “Star Brigade” skirmished with elements of Brig. Gen. John Hagood’s South Carolina brigade at Port Walthall Junction. The fighting accomplished little save increasing animosity between Smith and Gillmore, the latter having failed to support Heckman. On May 7, Butler wrote to Vermont Senator Henry Wilson that Gillmore “may be a very good engineer officer, but he is wholly useless in the movement of troops.”

With a five-brigade section of roughly 8,000 men, the Federals attacked the junction in force on May 7. Although the Confederates had only 3,000 men and six cannons under Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson, they took advantage of a lack of cohesion of Union Brig. Gen. William T.H. Brooks’ relatively inexperienced command. The fighting was fierce, but it was hardly a full-fledged battle. Brooks would finally fall back to Ware Bottom Church, later claiming he lacked the adequate strength to do more.

Union losses for the May 6-7 expedition, which claimed only a few hundred yards of quickly repaired track, were 413; the Confederate total was 280. Pickett directed Johnson to fall back to Swift Creek, which he believed was a better position for defending Petersburg.

More Lost Chances

Union naval forces were having no success either. On May 6, near Deep Bottom, a Confederate torpedo sank the gunboat Commodore Jones. The next day at Turkey Bend, Rebel artillery and infantry captured and burned USS Shawsheen, prompting Lee to show greater caution in subsequent river probes.

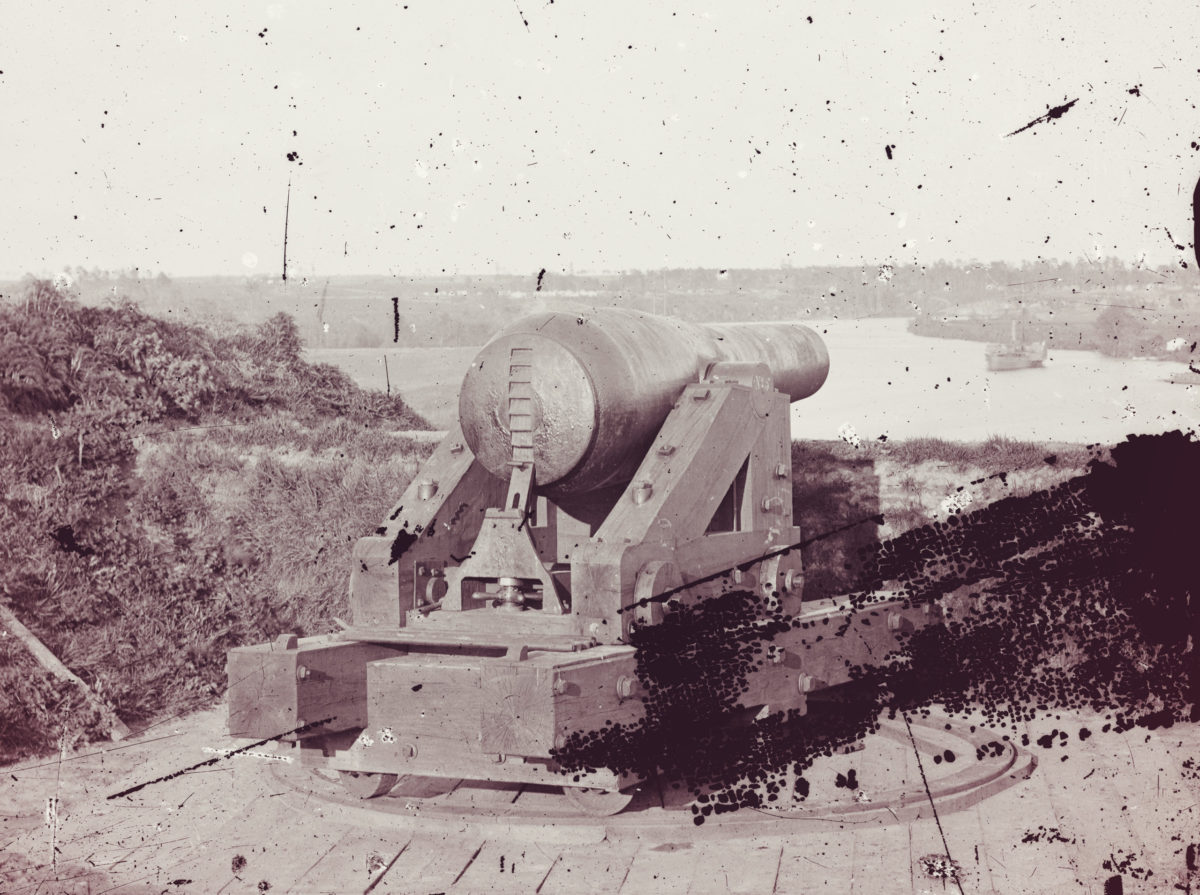

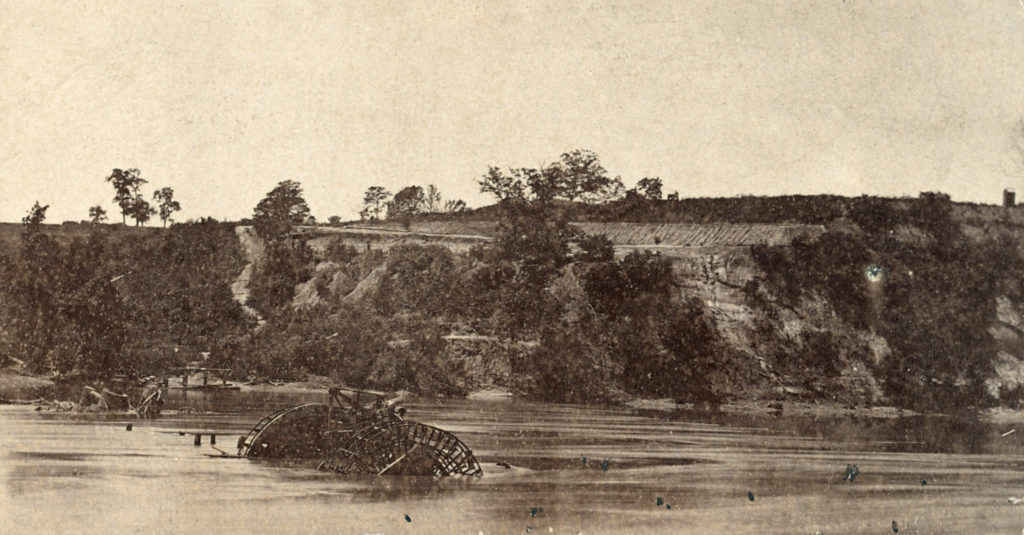

On May 8, a frustrated Butler began destroying the railroad between Richmond and Petersburg in preparation for a May 9 strike in which most of the army was to take part. As the 10th Corps threatened Drewry’s Bluff, the bulk of the 18th Corps would head to Port Walthall Junction to tear up track, while others probed toward Petersburg. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Charles Graham’s army gunboat flotilla, aided by Hinks’ USCT units, would try to level Fort Clifton, shielding Petersburg on the Appomattox.

Graham’s attack was a fiasco, with Samuel L. Brewster, the flotilla’s strongest ship, destroyed. Better news came from Gillmore, who diligently tore up track at Chester Station, and from Smith, who did the same at Port Walthall Junction. But a subsequent move on Petersburg in force by Butler and Smith was cut short, as elements of the 18th Corps found Johnson’s 4,300-man force at Swift Creek. Although Johnson lost about 600 men, mostly in a failed attack, the Federals failed to drive him off. Union Brig. Gen. Isaac Wistar probably summed it up best, calling the Swift Creek fighting “obscure in magnitude and barren of results.”

Butler, however, was generally pleased with the May 9 results and urged Smith and Gillmore to press on to Petersburg with another strike at Swift Creek while Hinks threatened from City Point. Neither Smith nor Gillmore objected but, after calling Butler incompetent in private, drafted their own plan of attack.

Their commander rejected the revision, of course, and rebuked his subordinates. But by then he had decided upon a new plan of action himself, basing it on reports that Richmond was vulnerable and erroneous news from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that Lee had been defeated at Spotsylvania. Butler felt it essential to attack Beauregard to prevent him from reinforcing Lee.

A brief, successful raid in southern Virginia by Brig. Gen. August V. Kautz’s cavalry brought Butler some good news, as did a determined stand by members of Gillmore’s vanguard during an attack at Chester Station that resulted in 249 Confederate casualties. In Richmond, the fighting at Chester Station produced panic, with Secretary of War James Seddon writing to Beauregard: “THIS city is in hot danger. It should be defended with all our resources to the sacrifice of minor considerations.”

Beauregard finally arrived at Petersburg on May 10, taking over for Pickett, who was ill. The next day, Beauregard was ordered to send six brigades under Hoke to Richmond, threatened by Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s cavalry. With the rail line broken, however, Hoke’s men had to traverse 10 miles of their route along the Richmond Turnpike, then march through Chesterfield Courthouse.

On May 11, Butler began moving toward Richmond with 25,000 men, leaving behind 5,000 to guard Bermuda Hundred. Fortunately for the Confederates, the Federals missed running into Hoke, whose line was mired in a miserable, rain-soaked march. Inadvertently, Butler had lost a prime chance to inflict a decisive defeat on Beauregard’s Confederates.

Lack of support from the Navy and Union cavalry continued to vex Butler. After Sheridan failed to penetrate the Richmond defenses, he shifted his command toward Bermuda Hundred on May 14. Butler hoped Sheridan would join his forces in attacking Chaffin’s Bluff, but “Little Phil”—his men exhausted—refused.

Butler also wanted Lee to cover his right flank with ironclads, but the admiral refused, as the river there was too shallow for his liking. On May 12, a reluctant Kautz launched a five-day raid in which his men tore up track, torched supplies, and pinned down some Rebel units in Petersburg, but otherwise did little more than deprive Butler of critically needed cavalry.

Fog of War

Incessant rain May 12-14 disrupted both sides’ progress. When Maj. Gen. William H.C. Whiting arrived in Petersburg on May 13, he was unexpectedly placed in command of a division to guard the Confederate stronghold city. As Gillmore had managed to outflank the Confederates, forcing them into a main defensive line at Drewry’s Bluff, Beauregard responded by rushing north from Petersburg, accompanied by Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Colquitt’s veteran Georgian brigade.

Beauregard was hoping for reinforcements from Lee’s army, feeling it would allow him to destroy Butler first before recombining against the Army of the Potomac. When Davis turned him down, Beauregard agreed to attack Butler on his own. The two, however, were not in agreement on how to use Whiting. Beauregard wanted his division to block Butler’s retreat path during the main Confederate attack; Davis preferred to have Whiting march to Drewry’s Bluff and serve as a flanking force.

When Beauregard requested naval support and for a delay until May 18 so Whiting could make it to Drewry’s Bluff, Seddon was incensed, insisting to Davis that Beauregard merely was stalling. Davis directed Beauregard to delay no longer, leaving the commander to revert to his original attack scheme.

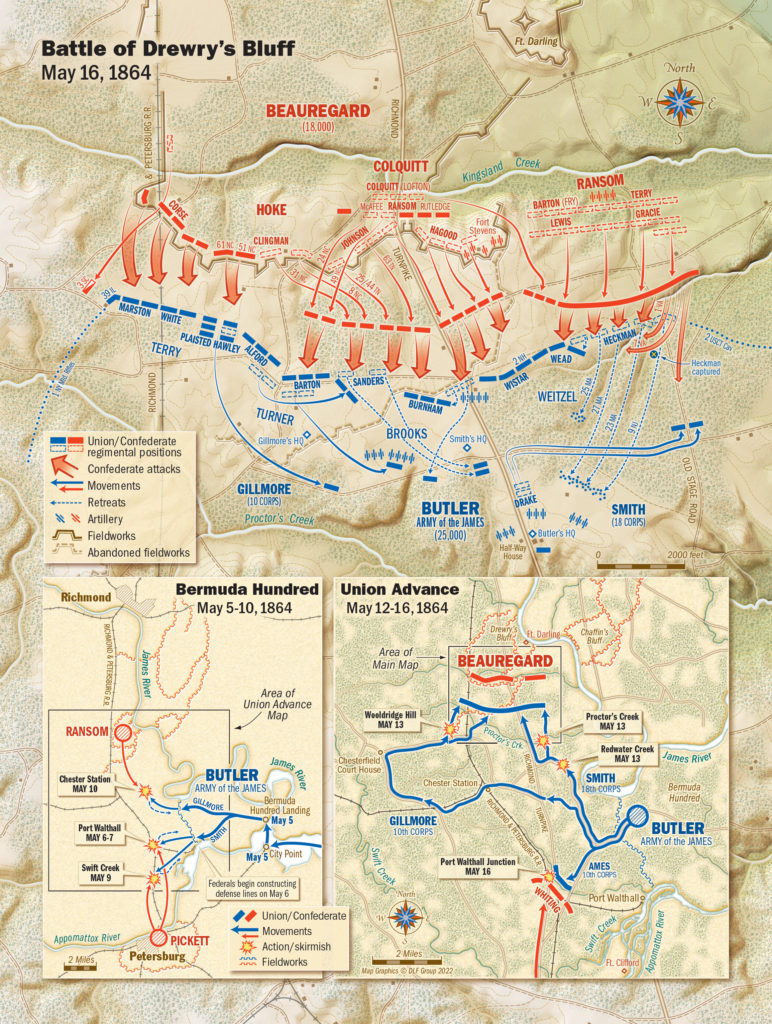

Beauregard had 18,000 men at his disposal, divided into four divisions under Maj. Gen. Robert Ransom; Hoke; Whiting; and Colquitt (in reserve). Ransom, whose brother Matt commanded a brigade under Colquitt, was instructed to attack the Union right flank down the Old Stage Road. That, Beauregard hoped, would draw in the rest of Butler’s command and allow Hoke to attack the Union left.

Ransom’s attack was scheduled for dawn May 16, but with a thick fog lingering over the fields and woods, he held off. Recalled Charles Loehr of the 1st Virginia: “[W]e were only aware that it was filled with our friends preparing for the desperate struggle ahead by the clear and distinct words of commands from invisible officers marshalling an invisible host.” The fog persisted, however. Finally, at 4:45 a.m., Ransom realized he could wait no longer and ordered the attack to proceed.

Hit first, the stunned 2nd USCT Cavalry fled so swiftly that it exposed the 9th New Jersey’s right flank. Overrun by Brig. Gen. Archibald Gracie’s Confederates, the 9th would lose Colonel Abram Zabriskie, mortally wounded, and had 200 men surrender.

The other regiments in Heckman’s command held briefly, forcing Gracie’s men to take cover. But Colonel William Terry’s Brigade surged forward to force a collapse. Heckman was captured, and both the 23rd and 27th Massachusetts lost their commanders.

Despite suffering 700 casualties, mostly as prisoners, Heckman’s men inflicted heavy losses on the Rebels. Terry had lost more than 300 men, and three of Gracie’s regimental commanders were wounded. Even worse, in the fog Gracie’s and Terry’s brigades dissolved into mobs, making it hard to reestablish a battle line. Many soldiers, in fact, simply plundered the Union camp.

A scratch brigade under Colonel Frederick F. Wead refused the Union right flank and held fast, but the rest of Ransom’s Division surged forward. As a defensive measure, Smith ordered telegraph wire strung up between tree stumps and ordered his artillery to the rear. Smith was perhaps prudent to fear his guns would be overrun, but robbed his men of needed firepower. Nevertheless, the Rebel attack failed, and the fighting devolved into desultory long-range firing.

During a frontal assault by Johnson and Hagood on Brooks’ position at 6:30 a.m., Hagood’s men came under heavy fire after getting tangled in the wire Smith had strung around the tree stumps. The “boys were pumping lead into them as fast as they could load and fire,” wrote Martin A. Haynes of the 2nd New Hampshire. “The rebs came on again and again, until the ground in front of the Second was carpeted with dead and wounded.”

Colquitt sent in a brigade to help, but it failed to penetrate the Union lines. In the confusion, however, “Baldy” Smith moved Wistar’s brigade out of the line before reversing his decision. Taking advantage, Hagood swept into a salient and captured several cannons.

Johnson’s attack devolved into confusion. According to R.C. Sanders of the 25th/44th Tennessee, “there was a heavy fog hanging over the works, so thick that it was with difficulty a Federal could be distinguished from a Confederate.” The fog allowed some of Johnson’s men to get lodgments in the line. In capturing a single cannon, however, the 63rd Tennessee would lose half its strength.

Despite some success, Johnson’s and Hagood’s soldiers were worn out. Most of the senior regimental officers had gone down, killed or wounded. Attempting to save the attack, Hoke sent the 8th and 61st North Carolina from Brig. Gen. Thomas Clingman’s Brigade to bolster Johnson, only to have them get lost in the fog and veer left. Their subsequent strike was ineffective.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Beauregard also sent the 24th and 49th North Carolina regiments, part of Rutledge’s command, to assist Johnson’s right. Colonel Leroy Magnum McAfee led this detachment, but both regiments also got lost in the fog and wandered into Union Colonel William B. Barton’s brigade. McAfee was wounded in the failed attack.

The rest of Hoke’s Division attacked the 10th Corps’ position. Clingman struck three brigades with only the 31st and 51st North Carolina and was easily repulsed. But the attack by Brig. Gen. Montgomery D. Corse’s Brigade on Gillmore’s left flank had some success. Though Corse was wounded, he remained at the front. Yet, as Clingman withdrew, Union flanking fire on Corse’s men ignited a long-range firefight.

By 10 a.m., Beauregard called off further attacks. It appeared Butler had won the battle, but the Union high command somehow unraveled. Beginning about 7:45 a.m., Smith withdrew to Half-Way House, then ordered Brig. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel’s division to attack Ransom’s disorganized forces. When Weitzel was unable to form his men, Smith decided to continue the retreat.

Ordered by Butler to attack, Gillmore instead concocted a complicated plan to disengage the 10th Corps toward Proctor’s Creek, as Smith’s retreat had created a gap between the two corps. Once new lines were formed, he hoped, the 10th Corps could attack.

Gillmore’s retreat began about 9:30 a.m. The 39th Illinois made a spirited stand in the process, losing one-third of its men. By 2 p.m., Butler had established a new line near Half-Way House and Proctor’s Creek—but at a heavy cost.

By now, Beauregard’s hopes were on Whiting, who had departed Petersburg about 5 a.m. with about 5,000 men under Brig. Gens. James Martin and Henry Wise, as well as two regiments of cavalry under Brig. Gen. James Dearing and a 10-gun artillery unit under Colonel Hilary P. Jones. Whiting soon ran into Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames’ brigade, the Union army’s rearguard at Port Walthall Junction. About 8:30 a.m., Jones’ guns opened fire as Wise prepared to charge. Ames withdrew north, and though he would receive reinforcements, by 11 a.m. Whiting had occupied Port Walthall Junction.

Whiting stopped there, however. Exhausted from a lack of sleep and likely feeling the effects of alcohol withdrawal, he apparently never heard the sounds of battle at Drewry’s Bluff—his attack signal. It proved critical. Rather than advance, Whiting sent ahead only Dearing, prompting Colonel David Harris, Beauregard’s chief engineer, to sneer: “Had he had a single dram…to clear his brain, Butler and his whole army would have been prisoners of war.”

At 1:15 p.m., Davis arrived at Drewry’s Bluff to oversee a seeming victory. Hearing rapid gunfire to the south, he proclaimed, “Ah, at last!” What Davis heard, however, was skirmishing between Dearing and Union stragglers at Chester Station. Dearing later contended that a vigorous pursuit would have paid off handsomely and had indeed advised Whiting to attack. By 1:30 p.m., Ames had received reinforcements and Whiting retreated to Swift Creek. A skittish Butler did not capitalize, however, finally ordering a retreat at 4 p.m.

The fighting that day had cost the Confederates nearly 3,000 casualties, the Federals roughly 4,100. The first three hours, according to Captain William H. Harder of the 23rd Tennessee, had been “one of the most terrible actions recorded in the war’s rugged history.” Wistar echoed that, calling it “one of the hardest fought combats of the war.”

Regret on Both Sides

The Union high command clearly failed at Drewry’s Bluff, as Smith and Gillmore had been too tentative overall and Butler chose to retreat despite tactical success. All the same, the Confederates hadn’t done much better. Coordination had been poor, and many of the soldiers blamed Ransom and especially Whiting. “[T]he hand of Fate had penned the decree of our defeat,” wrote Thomas R. Roulhac of the 49th North Carolina, “but of all those [blunders] which contributed to our downfall, that of…Whiting, on the afternoon of May 16, 1864, was one of the most glaring and stupendous.”

Drewry’s Bluff was an incomplete victory that left many Rebels dissatisfied, including Davis. Yet it was a victory. Morale soared in the Rebel ranks. More important, Butler no longer seemed a threat to Richmond. Wrote Colonel Alfred Roman of Beauregard’s staff: “The day was ours. Butler’s army was driven back, hemmed in, and reduced to comparative impotency, though not captured.”

After the war, Beauregard surmised: “The communications south and west of Richmond were restored. We had achieved the main object for which our forces had encountered the enemy.” The Union defeat and withdrawal meant that Lee would receive those reinforcements. It also meant that the already shaky morale in the Army of the James dipped even further. Colonel Joseph Hawley, for one, summed up the feelings of many when he wrote “I have no faith nor hope.”

Drewry’s Bluff was the campaign’s biggest and most important battle, but the fighting was hardly over. As Butler grappled with uncertainty, Beauregard amped up his aggressiveness. His May 20 victory at Ware Bottom Church added to Butler’s duress and allowed Beauregard to send more men to Lee’s aid. Although Beauregard wanted to use artillery to close off the James, his lack of enough heavy weaponry and the presence of Lee’s formidable fleet made that wishful thinking.

Drewry’s Bluff remained a point of anguish for Beauregard, who long grumbled, “We could and should have captured Butler’s entire army.” Davis’ already poor opinion of Beauregard only worsened and became one of mutual hatred after the war. Nevertheless, the Bermuda Hundred Campaign was among the Confederacy’s last measurable strategic victories.

For the Union, the defeat was bitter. Butler succeeded in tying down troops until May 17 but failed to take either Richmond or Petersburg. Understandably it hung as a cloud over his record, as well as for Gillmore and Smith. All three men disappeared from the Army of the James by war’s end, finishing the conflict with tarnished military reputations.

Sean Michael Chick, like P.G.T. Beauregard a native of New Orleans, is the author of Grant’s Left Hook: The Bermuda Hundred Campaign, May 5–June 7, 1864 (Savas Beatie, 2021).