On Friday the 13th of August 1948 U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Sterling P. Bettinger tried to land his Douglas C-54 Skymaster transport at Berlin’s Tempelhof Field. Aboard was a VIP passenger—Maj. Gen. William H. Tunner, the new director of operations for the seven-week-old Berlin Airlift. Unfortunately, recalled Tunner in his memoir Over the Hump, “at that moment everything was going completely to hell in Berlin. The ceiling had suddenly fallen in on Tempelhof. The clouds dropped to the tops of the apartment buildings surrounding the field, and then they suddenly gave way in a cloudburst that obscured the runway from the tower. The radar could not penetrate the sheets of rain.” One aircraft crashed; another blew out its tires braking to avoid the crash.

Bettinger joined a cluster of pilots circling over Tempelhof, waiting as ground controllers tried to sort out the mess. “The pilots filled the air with chatter, calling in constantly in near panic to find out what was going on,” Tunner recalled. “On the ground a traffic jam was building up as planes came off the unloading line…but were refused permission to take off for fear of collision with the planes milling around overhead. ‘This is a hell of a way to run a railroad,’ I snarled.”

Two months earlier the Cold War had heated up dramatically. Unhappy with plans by the Western Allies (France, Britain and the United States) to create a federal government uniting the portions of Germany they occupied, the Soviet Union in retaliation blockaded the American, British and French occupation sectors in isolated West Berlin. On June 19 the Russians blocked automotive and rail passenger service between western Germany and Berlin. On the 24th they halted all barge and rail freight shipments, cutting the primary supply and commerce links for more than 2 million Berliners. The only means left to the Western Allies to sustain the city was by air transport. “Members of the Soviet military administration in Germany celebrated when the blockade began,” wrote U.S. Air Force historian Roger Miller. “None had doubts that the blockade would succeed.” Major General Lucius Clay, military governor of the American occupied zone of Germany, recalled the Russians were “confident that it would be physically impossible for the Western Allies to maintain their position in Berlin.” The chaos Tunner and Bettinger encountered at Tempelhof seemed to validate Soviet confidence the airlift would fail.

A year later, though, it was the Western Allies who were celebrating. Between June 26, 1948, and Sept. 30, 1949, Allied transport planes completed 277,569 cargo flights, carrying 2,325,509 tons of supplies, into West Berlin. West Berliners had suffered a great deal, but they had endured, and the Western Allies’ position in the divided city had remained strong. On May 12, 1949, the Russians threw in the towel and reopened land and water access to the western sectors—without receiving any concessions regarding the formation of a West German government. (The airlift continued through September to build up emergency supply stocks in Berlin.) The airlift achieved what many thought was impossible: fulfilling the critical needs of a modern city’s population solely through air transport. Allied determination and organization had won the West’s first major victory in the Cold War.

On June 28, four days after the blockade began, the U.S. Departments of State and Defense briefed President Harry S. Truman on the situation. Miller, in his book To Save a City, notes the president quickly quashed any idea of withdrawal. “Abandoning Berlin, [Truman] affirmed, was beyond discussion,” Miller wrote. “The United States was in Berlin by agreement, and the Soviets had no right to push its forces out.”

British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin agreed. A former truck driver and union official, Bevin was the opposite of the stereotypical sophisticated English diplomat. Bevin had displayed his less-than-genteel manner at the July 1946 Paris Peace Conference. Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had hurled insults at the British during the meetings and continued the badgering at dinner one night. “Bevin exploded in rage,” wrote Giles Milton in his book Checkmate in Berlin. State Department official Charles Bohlen recalled Bevin “rose to his feet, his hands knotted into fists, and started toward Molotov, saying, ‘I’ve had enough of this, I ’ave.’ For one glorious moment it looked as if the foreign minister of Great Britain and the foreign minister of the Soviet Union were about to come to blows.” (Security intervened, defused the situation and spoiled the moment.) When the Soviets blockaded Berlin, Bevin demanded the Western Allies stand firm. Milton quotes him as saying he “did not want withdrawal to be contemplated in any quarter.” Ordered to stay in Berlin, the American and British military had to figure out how to maintain their position there.

Hardly any Western officials thought an airlift could satisfy Berlin’s needs for an extended period. “Rather it was a stopgap measure,” Miller wrote, “an expedient that enabled Western leaders to buy the time…to negotiate without either the need to give in at some point to Soviet pressure or to escalate the situation beyond control.”

A 1945 agreement between the wartime Allies established six corridors for aircraft travel to and from Berlin—three from the Soviet occupation zone, two from the British and one from the American. The Russians, loath to provoke armed conflict, didn’t contest the three western corridors. Anyway, they thought the airlift would fail. Before the blockade Berlin imported approximately 12,000 tons of supplies a day. American, British and French occupation officials calculated that West Berlin’s population, Western Allied personnel and their families would require a minimum of 4,500 tons daily to survive, while at most Royal Air Force and U.S. Air Force transport aircraft in Europe could carry 1,000 tons a day. West Berlin was not wholly sealed off from the outside world. It still received supplies from the Soviet zone, but not nearly enough to survive.

Clay added his voice to Truman’s and Bevin’s, arguing forcefully for the West to do whatever necessary to stay in Berlin. On June 25 Clay warned Army leadership that the West’s credibility in Germany could be mortally wounded if they abandoned the western sectors. “Thousands of Germans have courageously expressed their opposition to Communism,” he told them. “We must not destroy their confidence by any indication of departure from Berlin.”

During World War II Clay had established a reputation in the Pentagon as a logistical and managerial wizard. When supplies for Allied forces in Europe had backed up in the freshly liberated port at Cherbourg, Clay unsnarled the mess. That gravitas helped Clay convince others the Western Allies could supply all of Berlin’s needs by air. In late July he advised Washington that if it sent larger cargo aircraft, and many more of them, the U.S. and British aircrews could fly enough missions each day to keep West Berlin alive. Air Force leadership had serious doubts, as satisfying Clay’s wishes would leave it with few cargo aircraft for its growing list of missions worldwide. Regardless, Air Force Chief of Staff Hoyt Vandenburg affirmed that if Washington committed itself fully to the mission, Berlin could be supplied by air. Truman gave the go-ahead, and Clay got his resources.

The Americans and British had actually been airlifting cargo into West Berlin since April. That month the Soviets had imposed restrictions on Western Allied rail travel to West Germany. Considering it an omen of traffic disruptions to come, the Western Allies started stockpiling food and coal in West Berlin. Some of those supplies came by air in an operation dubbed the “Little Lift.” When the Soviet blockade started in June, U.S. and British cargo planes ramped up that air operation. But the primary cargo airframe in the European theater was the Douglas C-47 Skytrain. Most were World War II leftovers, some still bearing their black-and-white D-Day invasion stripes. At most the twin-engine C-47 could carry little more than 3 tons.

Allied Planes Flown in the Berlin Airlift

United States

Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter

Consolidated B-24 Liberator

Consolidated PBY Catalina

Douglas C-47 Skytrain and Douglas DC-3

Douglas C-54 Skymaster and Douglas DC-4

Douglas C-74 Globemaster

Fairchild C-82 Packet

Lockheed C-121A Constellation

Great Britain

Avro Lancaster

Avro Lincoln

Avro York

Avro Tudor

Avro Lancastrian

Bristol Type 170 Freighter

Douglas DC-3 (Dakota)

Handley Page Hastings

Handley Page Halifax

Short Sunderland

Vickers VC.1 Viking

The four-engine C-54 Skymaster, on the other hand, could carry more than 13 tons of cargo. Thus, the Air Force started deploying C-54 squadrons from bases around the world to western Germany. (The Navy also provided two squadrons.) Many flew to Germany with only hours’ notice. Lieutenant Gail Halvorsen, a C-54 pilot deployed from Alabama, recalled landing in Rhein-Main Air Base near Frankfurt with a contingent of Skymaster pilots and crewmen. Within two hours one of those crews was flying a plane to Berlin. Eventually, 225 C-54s were assigned to the airlift.

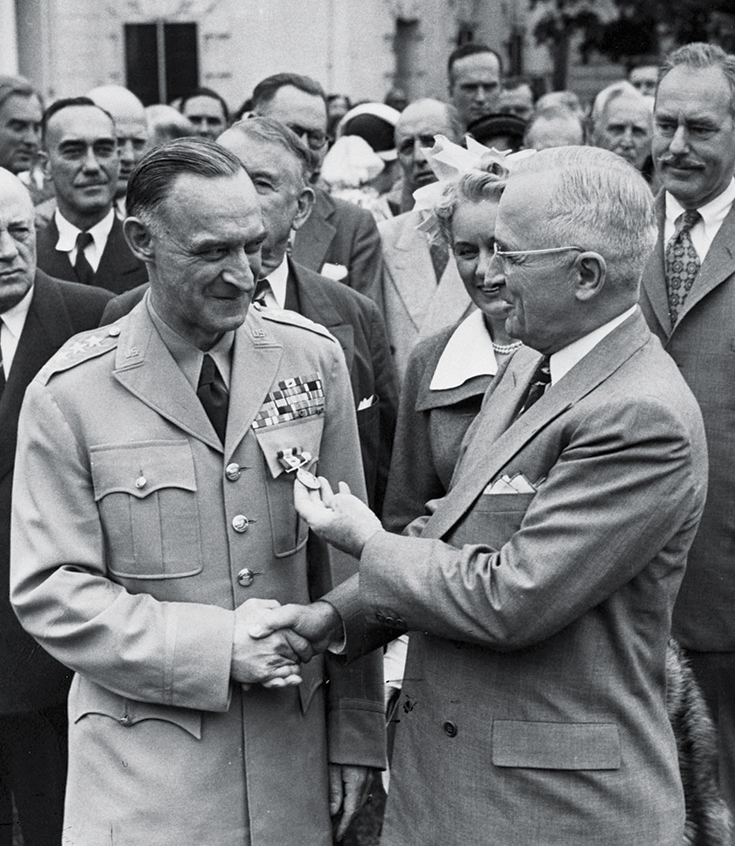

The airlift received new leadership—Tunner, who arrived in Germany on July 28. He would command the Combined Airlift Task Force (CALTF), an ad-hoc combined command that would coordinate and direct U.S. and British airlift operations. He’d already earned the nickname “Tonnage Tunner” for having led U.S. airlift operations over the Himalayas (the “Hump”) into China during World War II. Renowned as an air transport expert, he helped create the Army Air Forces Ferrying Command. He’d been watching the early stages of the Berlin Airlift from Washington. When Truman resolved to intensify the effort, Tunner got his chance.

The early days of the airlift were dramatic. Newspapers and news broadcasts ran stories of pilots rushing out to cargo aircraft parked haphazardly around their airfields and zooming off with them into the German skies. To readers and viewers worldwide it looked inspiring and dramatic. Yet to Tunner it reeked of inefficiency. (Halvorsen described the early days as a “real cowboy” operation.) “The actual operation of a successful airlift is about as glamorous as drops of water on stone,” said Tunner, in Over the Hump:

There’s no frenzy, no flap, just the inexorable process of getting the job done. In a successful airlift you don’t see planes parked all over the place; they’re either in the air, on loading or unloading ramps, or being worked on. You don’t see personnel milling around; flying crews are either flying or resting up so that they can fly again tomorrow. Ground crews are either working on their assigned planes or resting up so that they can work on them again tomorrow.

“Under Tunner,” wrote Miller, “the monotony of repetition replaced the romance of flying.” Tunner set out to organize the airlift in exacting detail and refine it into a smooth, efficient operation.

In the first few months of the airlift chaos was not uncommon in the skies directly over Berlin. Aircraft from eight different airfields in Germany converged on just two in Berlin—Tempelhof, in the American sector, and RAF Gatow, in the British sector. When poor weather or problems on the ground made it difficult to land, planes would end up “stacked,” circling at different altitudes as they waited. Tunner ended up in one of those stacks over Tempelhof, in cloudy weather and heavy rains, on that “Black Friday” August 13 flight to Berlin. “A huge, confusing, milling mass of aircraft circled in a stack from 3,000 to 12,000 feet,” wrote Miller, “in danger of collision or of drifting out of the corridors completely.”

Tunner radioed Tempelhof tower: “This is 5549, Tunner talking, and you better listen. Send every plane in the stack back to its home base.” Afterward, Tunner implemented new landing procedures for the Berlin airfields. If an aircraft missed its landing approach, it wouldn’t circle and try again; it would return to western Germany. Such was a far safer and more efficient way to manage landing operations. Air traffic controllers were no longer tasked with inserting stray aircraft back into the landing pattern; they could focus instead on managing a steady stream of incoming planes. “In the same 90 minutes it took to bring in nine aircraft stacked over Berlin,” Miller wrote, “the airlift could land 30 C-54s carrying 300 tons using the straight-in approach and landing at three-minute intervals.”

Airlift controllers closely managed the ways planes flew in the corridors. They used time spacing to separate the aircraft, usually in three- to six-minute intervals. Aircraft announced the times they passed key radio beacons. Each aircraft crew knew the tail numbers of the three aircraft in front of and behind them. When they heard an aircraft announce its position, they would adjust their speed or heading to keep their proper place in the airflow. Any plane that lost radio communications or couldn’t keep its place in the flow had standing orders to fly home.

Pilots flew by instrument flight rules, even if the weather was good. Traffic in the corridors was one-way. The British used six airfields, and all sent their aircraft to Berlin through the northern airlift corridor, which originated north of Hamburg. The Americans flew from bases at Rhein-Main and Wiesbaden through the southern corridor. All aircraft returned to western Germany through the central corridor, which emptied near Hannover.

Tunner realized he couldn’t increase tonnage by adding more aircraft to the airlift. Washington had only so many planes to send, and the traffic patterns in the air corridors and parking aprons at the airfields were already full. So, he looked for other ways to maximize cargo throughput. The northern corridor was shorter than the southern, so planes that used it could fly more round trips per day. The American C-54s could carry more cargo than the C-47s and other aircraft the British were using, so Tunner stationed some American squadrons in the British zone. The USAF stripped unnecessary equipment (such as the LORAN long-range navigation systems) out of the C-54s to enable them to carry more cargo.

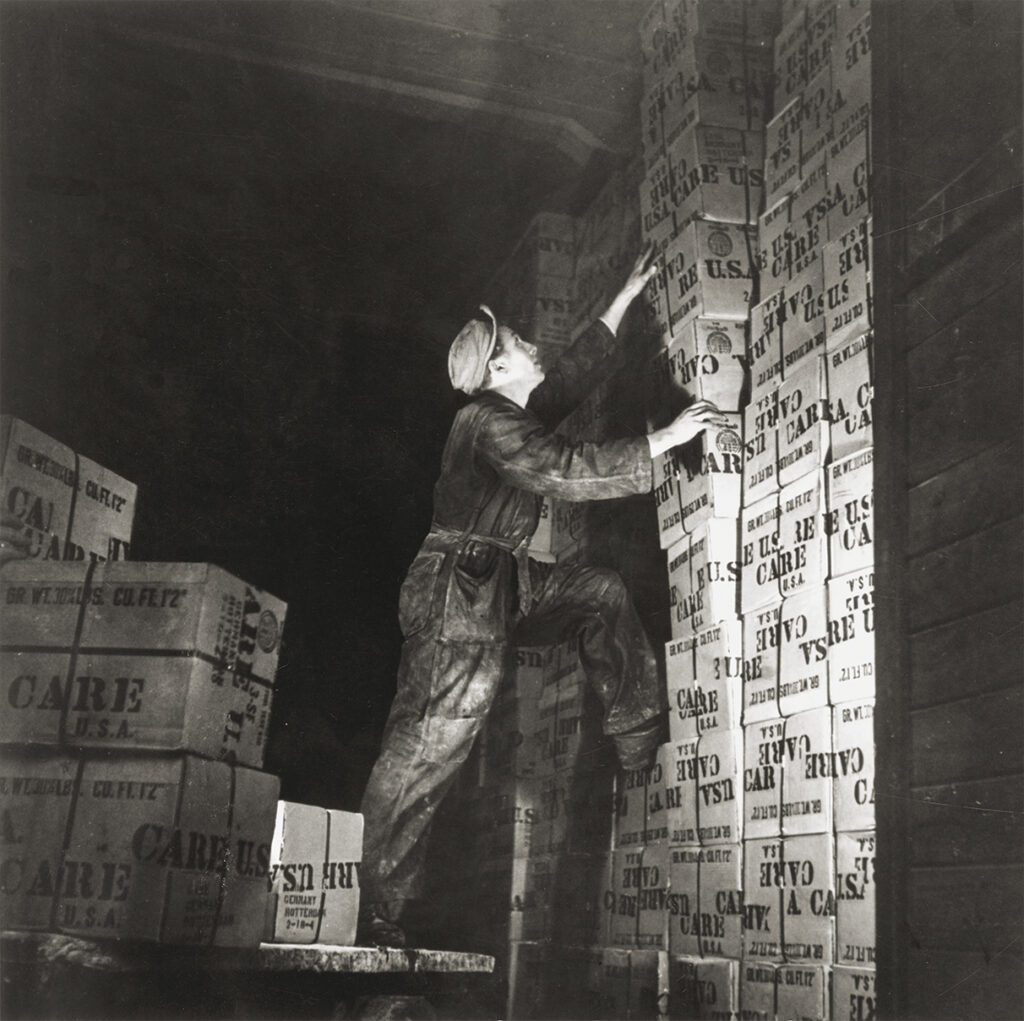

The more time a plane spent on the ground, the less cargo it could carry to Berlin. CALTF planners examined every step in the loading/unloading process, looking for ways to cut time, increase safety margins and improve overall performance. Logistics planners realized that if multiple pieces of equipment were used to load aircraft, that added time to the loading process (and increased chances an errant forklift could damage a plane). CALTF switched to putting a plane’s cargo load on just one truck. The truck driver would shadow the Follow Me jeep that guided a newly landed plane to its parking spot. As the crew shut down its engines, German workers would jump from the truck, ready to load the plane for its return trip to Berlin. In Berlin aircrews were told to stay by their aircraft during loading/unloading, instead of going inside for coffee. Mobile canteens, manned by pretty Fräuleins, carried refreshments out to the flight line. After pilots informed Tunner their planes flew sluggishly when carrying coal, CALTF personnel weighed the coal bags. They found that overzealous German workers were packing as much coal in the bags as they could—more than the bags were supposed to hold—resulting in overloaded planes.

Airlift Medal

Authorized by Congress on July 20, 1949, the Medal for Humane Action recognized any service member who performed at least 120 days of duty in direct support of the Berlin Airlift. It depicts a Douglas C-54 Skymaster over a wheat wreath and the coat of arms of Berlin.

The French weren’t part of the CALTF operation. They had few cargo aircraft, and Allied planners were concerned French-speaking pilots might have problems communicating with British and American air traffic controllers. The French did contribute one memorable episode to the airlift story, though. To improve the flow of cargo into Berlin, the Western Allies in November 1948 opened a third airfield, Tegel, in the French occupation zone. Partially obstructing its runway was a broadcast tower used by Soviet-controlled Berliner Rundfunk (Radio Berlin). The French formally asked the Soviets to move the tower, at Allied expense, but were refused. Then one morning that December General Jean Ganeval, the French commandant in Berlin, summoned to his office American personnel working on the airfield. Some minutes into the meeting they heard an explosion outdoors. The Americans rushed to the window of Ganeval’s office in time to watch the tower collapse to the ground. According to several accounts, Ganeval turned to the shocked Americans and said simply, “You will have no more trouble with the tower.” When the angry Soviets asked Ganeval how he could have done something like that, the French commandant reportedly replied, “With dynamite.”

The Berlin Blockade ultimately backfired on the Soviets. It increased support in the American, British and French occupation zones for the planned West German government. “American intelligence analysts reported widespread demoralization and membership loss among Communists in all parts of [Germany],” note Army historians Donald A. Carter and William Stivers. “The Soviet coercive measures against Berlin strengthened the Western position in Germany as a whole.” Alarmed Western European nations became more interested in collective security initiatives, an interest that led to the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in April 1949.

The airlift, by contrast, proved a public relations bonanza for the Western Allies. In April 1949, on Easter Sunday, the airlift staged a one-day transport blitz during which 1,398 flights carried in 12,941 tons of cargo—the same amount West Berlin had received daily by rail, road and water during peacetime. “I hope that the Communists, who have spent so much time insulting us, will realize that we really aren’t such a soft democracy,” crowed Brig. Gen. Frank L. Howley, the U.S. commandant in Berlin, after the blockade ended. The airlift also improved German-American relations. American newsreels praised West Berliners for their determination to endure the blockade. German children played “airlift” with toy planes. Halvorsen gained headline acclaim as the “Candy Bomber,” dropping candy from handkerchief parachutes to crowds of grateful West Berlin children.

Clay retaliated against the Soviets with his own blockade of raw materials and finished goods that eastern Germany desperately needed from western Germany. For instance, Germany’s best source for coking coal, critical in steel production, were the mines of the Ruhr, in the British occupation zone. Meanwhile, the economy of the Soviet occupation zone, still struggling after World War II, was losing many of its own resources and products to the Russians for their own use. “The eastern zone economy suffered grievously from the counterblockade,” Carter and Stivers wrote. By February Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, succumbing to a public relations nightmare of his own doing, had signaled American diplomats he was keen to end the crisis.

Yale historian John Lewis Gaddis called the Berlin Airlift “the first clear Soviet defeat in the Cold War.” In hot wars nations inflict defeat on one another using soldiers, armor, airpower and high explosives. The Cold War was a different kind of war, so it’s fitting that its first major victory was won not through violence, but by persistence and excellence in effort. “I don’t have much of a natural sense of rhythm,” Tunner wrote in his memoir. “I’m certainly no threat to Fred Astaire, and a drumstick to me is something that grows on a chicken. But when it comes to airlifts, I want rhythm.” The Americans and British achieved rhythm in the skies over Berlin. They created an airborne conveyor belt that kept a city alive, helped transform the Germans and Americans from wartime enemies into peacetime friends, united Western Europe and inspired freedom-loving people across the globe.

Don Smith is a retired U.S. Army Reserve officer with degrees in history and intelli-gence studies. He’s worked as a defense contractor with various Defense Department agencies for more than 30 years. For further reading he recommends To Save a City, by Roger Miller; Checkmate in Berlin, by Giles Milton; and The City Becomes a Symbol, by William Stivers and Donald A. Carter.

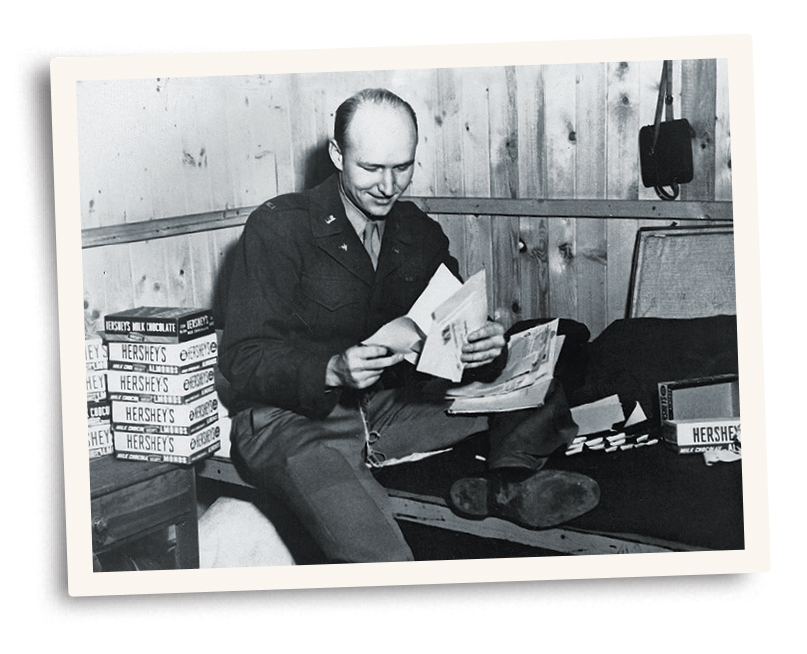

The Irrepressible ‘Candy Bomber’

Gail Halvorsen joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1942 and trained on fight-ers with the Royal Air Force. Reassigned to military transport service, Halvorsen remained in the service at war’s end. He was flying Douglas C-74 Globemasters and C-54 Skymasters out of Mobile, Ala., when word came in June 1948 that the Soviet Union had blockaded West Berlin. During the 15-month airlift (Operation Vittles), American and British pilots delivered more than 2.3 million tons of supplies to the city. But it was Halvorsen’s decision to airdrop candy to children (Operation Little Vittles) that clinched an ideological battle and earned him the lasting affection of a free West Berlin. The beloved “Candy Bomber” died at age 101 on Feb. 16, 2022.

In 2009 Military History editor David Lauterborn was fortunate enough to interview Halvorsen. Following is an excerpt of their conversation, available in full online at Historynet.com/candy-bomber-gail-halvorsen.

What prompted you to start dropping candy?

At the end of the [Tempelhof] runway, in an open space between the bombed-out buildings and barbed wire, kids were watching the air-planes coming in over the rooftops. They came right up to the barbed wire and spoke to me in English: “Don’t give up on us. If we lose our freedom, we’ll never get it back.” American-style freedom was their dream. Hitler’s past and Stalin’s future was their nightmare. I just flipped. Got so interested, I forgot what time it was.

I looked at my watch and said, “Holy cow, I gotta go! Goodbye. Don’t worry.” I took three steps. Then I realized—these kids had me stopped dead in my tracks for over an hour, and not one of 30 had put out their hand. They were so grateful for flour, to be free, that they wouldn’t be beggars for something extravagant. This was stronger than overt gratitude—this was silent gratitude. How can I reward these kids?

I went back to the fence and pulled out my two sticks of Wrigley’s Doublemint, broke them in half and passed the four pieces through the barbed wire….I told them, “Come back here tomorrow, and when I come in to land, I’ll drop enough gum for all of you.”

One asked, “How do we know what airplane you’re in?”

“I’ll wiggle the wings.”

“Vas ist viggle?” he asked.

How did you work it?

My copilot and engineer gave me their candy rations—big double handfuls of Hershey, Mounds and Baby Ruth bars and Wrigley’s gum. It was heavy, and I thought, Boy, put that in a bundle and hit ’em in the head going 110 miles an hour, it’ll make the wrong impression. So, I made three handkerchief parachutes and tied strings tight around the candy. The next day I came in over the field, and there were those kids in that open space. I wiggled the wings, and they just blew up—I can still see their arms. The crew chief threw the rolled-up parachutes out the flare chute behind the pilot seat.

As your efforts grew in scope, did anyone notice?

[One day] an officer met the airplane and said, “The colonel wants to see you right now.” So I went in, and he says, “Whatcha doing, Halvorsen?”

“Flying like mad, sir.”

“I’m not stupid. What else you been doing?” And he pulled out a newspaper with a big article and a photograph of my plane and the tail number. So I told him. He understood, and airlift commander General William Tunner said, “Keep doing it!”

What kept you going?

Without hope the soul dies. And that was so appropriate for the day. In our own neighborhoods people have lost hope, lost function because they have no outside source of inspiration. The airlift was a symbol that we were going to be there—service before self.

Operation Little Vittles dropped more than 21 tons of candy during the airlift. How does that total strike you?

All from two sticks of gum in 1948—unbelievable!

This story appeared in the 2023 Summer issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.