To the weary troops of General Joseph E. Johnston’s command occupying the fresh breastworks in the North Carolina woods south of Bentonville, it must have seemed an eternity waiting for Major General William T. Sherman’s army to enter the trap. Soon, to judge from the sounds of approaching firing, the dismounted cavalry would break off the skirmish in the ravine ahead and pass through the line of battle to re-form on the flanks. Then, when the Union infantry hit the works that blocked the Goldsboro Road, the real scrap would begin. Troops scanned the woods at the far side of the field for signs of movement and surveyed the rear for signs that Lieutenant General William J. Hardee’s two divisions would arrive in time.

Hardee’s men had been in almost daily contact with the enemy for nearly two weeks, but most of those present on this Sunday morning were new to the command. Survivors from General John B. Hood’s Army of Tennessee (which had been destroyed at Nashville), Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s Division fresh from Virginia, artillery regiments grown stale from garrison duty and even a youthful brigade of North Carolina Junior Reserves (“the seed corn of the Confederacy”) were assembled at Bentonville in this last desperate attempt to block Sherman’s northward sweep through the Carolinas. Ten days ago they had been scattered from Kinston to Charlotte; never before had they fought together as a unit.

In addition to obvious weaknesses in organization, this makeshift aggregation of about 20,000 was top-heavy in command. Johnston, who on February 23 had been assigned the task of stemming Sherman’s invasion, was assisted by Lt. Gen. D.H. Hill, a brilliant but truculent combat officer; General Braxton Bragg, who had been relieved from command of the Army of Tennessee after the fiasco atop Missionary Ridge in November 1863; Maj. Gens. Lafayette McLaws and Hoke, both of whom had received their training under Robert E. Lee; and Lt. Gens. Stephen D. Lee and A.P. Stewart, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham and Hardee, all capable corps commanders who had fought against Sherman in the West. The cavalry was in the aggressive hands of Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s successor, and Lt. Gen. Joseph Wheeler. Famous names, these, but many had not worked together before and several were conspicuous for previous failures.

Prospects for victory seemed dreary. Sherman commanded a veteran force of some 60,000, which he had divided into two permanent wings to attain greater mobility. The Left Wing, comprising the XIV and XX corps, under Maj. Gen. H.W. Slocum, was now approaching from the west; the Right Wing, led by Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard, was known to be some distance to the south and east, in the direction of Goldsboro. Faulty maps exaggerated the distance separating the two and led Johnston to believe that he could overwhelm the Left Wing before the other could come to its assistance. If Sherman’s army was permitted to reach Goldsboro, it would be joined there by two additional corps under Brig. Gens. A.H. Terry and J.M. Schofield, marching inland from the coast, and Sherman would then have 100,000 men to add to Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant’s beleaguering army at Petersburg. This must be prevented; to delay would be to forfeit the campaign.

Under the protective cover of Hampton’s skirmishers, Johnston made his dispositions. Bragg, nominally in charge of Hoke’s Division, was given the Confederate left, straddling the Goldsboro Road. Hardee, as soon as his divisions reached the scene, was to take up position en echelon to the right, with Stewart’s corps prolonging the line still farther until it ran virtually parallel to the Goldsboro Road. The Confederate line resembled a sickle, with the cutting edge poised to slash away at the Left Wing as it marched along the road to Goldsboro. But the dense woods and thickets hindered deployment, and all troops had not reached their assigned positions when Hoke’s pickets were driven back by advance units of the XIV Corps. Soon hundreds of blue-clad infantry could be seen moving across the fields of Cole’s plantation, totally unaware that between them and Goldsboro lay Johnston’s entire army.

Sherman anticipated no attack and in fact had left Slocum’s wing early that morning to be with the Right Wing when it reached Goldsboro. He had ridden only a short distance when he heard artillery fire, but a message from Slocum convinced him that it was only stubborn cavalry resistance. The Right Wing continued to press toward Goldsboro.

For the men in Slocum’s command, March 19 began like any other day. At daybreak they were roused, and by 7 a.m. the leading regiments of Brig. Gen. William P. Carlin’s division, XIV Corps, had consumed their usual fare of hardtack and coffee and begun their march. For the first time in weeks they were blessed with a beautiful day. With bad weather and swamps behind them, and the peach trees in full bloom, the soldiers, warmed by the spring sun, stepped out “vigorously and cheerfully” in anticipation of a rest and fresh supplies at Goldsboro. “I would like to see [the Confederates] whaled,” one of the men wrote, “but would like to wait till we refit. You see that too much of a good thing gets old, and one don’t enjoy even campaigning after fifty or sixty days….”

They had moved but a short distance when they encountered Hampton’s dismounted cavalry. When these “didn’t drive worth a damn,” Slocum ordered Carlin to deploy and clear the road. Carlin’s leading regiments worked their way forward for five miles until, at 10 a.m., they encountered Hoke’s infantry posted behind rail works. Of course, they had no inkling yet that in the woods stretching off to their left, the Confederates were to be found in even greater numbers.

As soon as Carlin’s troops reached Cole’s house, Hoke’s artillery opened fire. Quickly, the first two brigades took shelter in a wooded ravine a few yards in front of the house. The third brigade deployed south of the Goldsboro Road. Still under the impression that the force blocking the road “consisted only of cavalry with a few pieces of artillery,” Slocum sent his first message to Sherman, advising him that no help would be necessary. Meanwhile Carlin’s division prepared to advance.

The men plunged into the woods. A few minutes passed, then a furious discharge of shots broke out on the left, where Brig. Gen. G.P. Buell’s brigade had stumbled into a hornets’ nest. One of Buell’s officers candidly described the scene: “The Rebs held their fire untill we were within 3 rods of the works when they opened fire from all sides and gave us an awful volley. We went for them with a yell and got within 5 paces of their works…I tell you it was a tight place….Men pelted each other with Ramrods and butts of muskets and [we] were finally compeled to fall back….[We] stood as long as man could stand and when that was no longer a possibility we run like the deuce….”

Quickly the brigades re-formed in the ravine east of the Cole house and set about improvising a defense line. South of the Goldsboro Road, Carlin’s third brigade was joined by Brig. Gen. James D. Morgan’s division, with two brigades posted behind log works and a third in reserve. Soon the leading brigade of Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams’ XX Corps arrived and took up position in a small ravine behind the one sheltering Carlin’s division. Thus two divisions plus a stray brigade, scarcely 10,000 men, found themselves facing a force of perhaps as many as 40,000 (with Robert E. Lee rumored to be present) and defending a line that was neither continuous nor well adapted to the terrain. Slocum sent another messenger after Sherman, this time pleading for reinforcements.

The initiative now passed to the Confederates. Johnston had hoped to attack sooner, but Carlin’s reconnaissance-in-force, though easily repulsed, had upset his timetable. Bragg felt sufficiently hard pressed to call for reinforcements, and Johnston ordered Hardee, whose troops were just arriving, to send one of his two divisions to support Bragg. McLaws’ Division arrived too late to be of any real assistance to Bragg, and his absence was felt on the Confederate right, where Hardee and Stewart were preparing their counterstroke. This weakened the right— the cutting edge—and delayed the Confederate attack.

By 2:45, Hardee’s troops were in position and the order was given to advance. Forming in two extended lines, the Confederates moved across the 600 yards that separated the two armies. It was a stirring sight, but to those watching anxiously from Bragg’s trenches it was painful to see how close together the battle flags were. Some regiments were scarcely larger than companies, and one division had shrunk to a pitiful 500 men!

Though they easily brushed aside the Union pickets, the gray lines staggered as they hit Carlin’s unfinished breastworks. Within minutes, however, a gap between the two blue brigades had been uncovered and, pouring through, the troops of Hardee, Stewart and Hill overran the second Union line some 300 yards beyond. “We lay behind our incomplete works and gave them fits,” Buell’s candid lieutenant reported to his family. “We checked them and held them to it until they turned the left of the 1st Brigade and of course that was forced to retreat….Our Brigade had to ‘follow suit’….When the Rebs got around us so as to fire into our rear [Carlin] Turned to the boys: ‘No use boys,’ and started back. The Regt. Followed and…it was the best thing we ever did. For falling back we met a line of Rebs marching straight for our rear and in 15 minutes more we would have been between two lines of the buggers….We showed…some of the best running ever did….”

The entire Union left was crushed by this well-executed blow and was driven back in confusion upon the XX Corps, then moving into position a mile to the rear. Carlin’s third brigade was driven into the lines of Morgan’s division south of the Goldsboro Road. Viewing the scene, one Union soldier was reminded of the confusion after Stonewall Jackson hit the XI Corps at Chancellorsville. Another, a staff officer, saw “…masses of men slowly and doggedly falling back along the Goldsboro road and through the fields and open woods on the left.…Minie balls were whizzing in every direction….Checking my horse, I saw the rebel regiments in front in full view, stretching through the fields to the left as far as the eye could reach, advancing rapidly, and firing as they came….The onward sweep of the rebel lines was like the waves of the ocean, relentless….”

Brigadier General Jeff Davis, commanding the XIV Corps, ordered Morgan to shift his reserve brigade to the left in order to plug the expanding gap. “Give them the best you’ve got and we’ll whip them yet.” Catching up the words “we’ll whip them yet,” the men of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Fearing’s brigade moved swiftly to the Goldsboro Road and charged into the left flank of the Confederates pursuing remnants of Carlin’s division. Taken in flank by additional Confederates coming down the Goldsboro Road, the brigade then retreated 300 yards and threw up a new line. Here the fighting gradually turned into an extended skirmish.

The Confederates next concentrated against Morgan’s division. Fearing’s withdrawal had created a gap that could not be plugged before three brigades from Hill’s corps smashed through and assaulted Morgan’s breastworks from the rear. Hoke wanted to exploit this breakthrough by throwing the weight of his division into the breach, but Bragg restrained him and ordered a frontal attack instead. For the next few minutes the fighting was desperate as men clubbed each other in dense thickets and swampy woods. Some Confederate officers claimed that it was the hottest infantry fight they had been in other than Cold Harbor. At one point Morgan’s surrounded soldiers were forced to fight simultaneously from both sides of their breastworks. Indeed, had it not been for the chance arrival of another brigade from the XX Corps, the day most certainly would have been lost. As it happened, Brig. Gen. William Cogswell’s brigade emerged from a tangled swamp behind Hill’s men as they assaulted Morgan’s rear lines. With a yell the brigade went at them and managed to push the Confederates back to the Goldsboro Road, where a battle line ultimately was stabilized.

The third and final Confederate attack was directed against the XX Corps, now in position a mile behind Carlin’s first line. Here Carlin’s division found refuge, and with Brig. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry guarding the exposed flank, a formidable line of trenches erected by the 1st Michigan Engineers and powerful artillery in support of fresh infantry, the XX Corps was ready and waiting.

The Confederate attack was delayed by Fearing’s threat to the left flank and the need to reorganize after the fight with Carlin’s division, so it was 5 p.m. before the gray lines emerged from the pine woods in front of the XX Corps. They were promptly greeted by a deadly barrage of artillery fire. Five times they tried to drive a wedge into the Union line; five times they withered before a storm of canister and bullets. The Union guns were especially devastating as grape and canister fire reportedly “barked the trees, cutting off the limbs as if cut by hand.” One Confederate division lost an estimated 25 percent. A survivor from the ranks, writing years after the battle, confessed, “If there was a place [at]…Gettysburg as hot as that spot, I never saw it.”

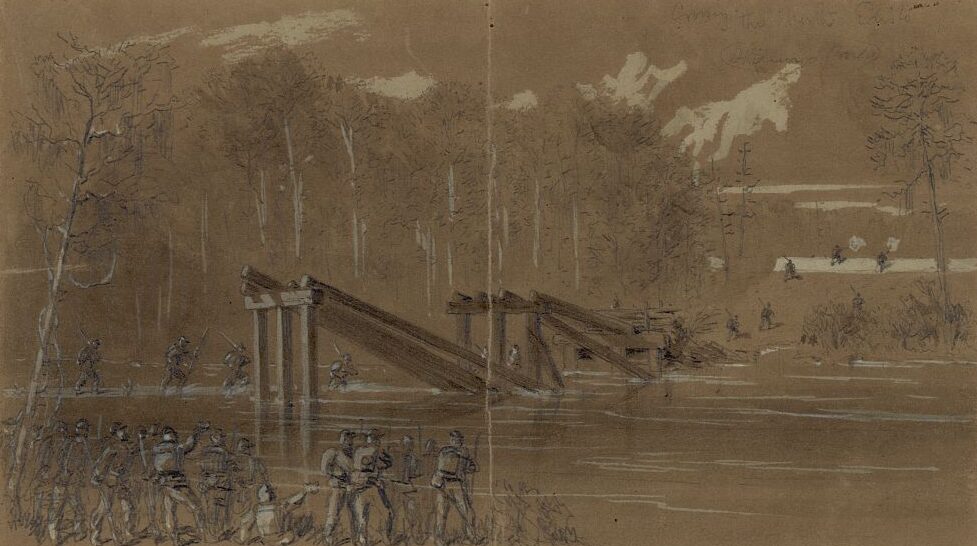

The final attack came at sundown. Gradually the firing died away as dusk faded into darkness and night separated the weary combatants. Hastily burying their dead, the Confederates withdrew to the positions they had occupied in the morning, but for Sherman’s troops the night of March 19 was one of sustained activity. It was late in the evening before Slocum’s appeal for help finally reached Sherman. Described as standing “in a bed of ashes up to his ankles, chewing impatiently the stump of a cigar, with his hands clasped behind him, and with nothing on but a red flannel undershirt and a pair of drawers,” Sherman issued orders setting the Right Wing in motion toward Bentonville. Marching by the shortest route, the Right Wing approached the battlefield from the direction of Goldsboro, behind Hoke’s line of breastworks. By noon on the 20th, Hoke had been forced to evacuate these and take up a new position parallel to the Goldsboro Road and near enough to command it. By late afternoon, Sherman’s army was united, and by nightfall Howard’s troops were firmly entrenched.

There was no heavy fighting on the 20th, only sharp skirmishing along the entire front. The Confederate position now resembled a “V” and in effect was an enlarged bridgehead covering Bentonville and the only bridge crossing the swollen waters of Mill Creek. The Union line roughly corresponded to the Confederate position except for the XX Corps, which remained where it had fought on the previous day. Johnston, now on the defensive, remained in his trenches, hoping to induce Sherman to attack, but Sherman had other plans. He was anxious to open communication with Schofield and Terry at Goldsboro and had no desire to bring on a general engagement until this had been accomplished. At dusk a heavy rain set in, lasting until morning. The Confederates, anticipating orders to fall back across Mill Creek, spent a sleepless night. Sherman himself expected and in fact hoped that Johnston would slip away during the night, as he had done so frequently during the recent campaign for Atlanta. At daybreak, however, his old antagonist was still there.

Throughout the 21st steady pressure was maintained against the Confederates. Union sharpshooters, lodged in the buildings of Cole’s plantation, annoyed the men opposite in Hill’s trenches. Farther to the right, the XV Corps wrenched an advanced line of rifle pits from Hoke and McLaws. The most serious fighting developed on the extreme Union right, where Maj. Gen. J.A. Mower worked two brigades from the XVII Corps around the Confederate left flank. By 4 p.m., these had seized two lines of rifle pits and were advancing toward the bridge that spanned Mill Creek—Johnston’s only line of retreat. But in his eagerness Mower had outdistanced the rest of the corps, and he now found himself three quarters of a mile in advance of the nearest supporting troops.

To meet this sudden thrust, the Confederates mounted a series of spirited counterattacks. Brigadier General Alfred Cumming’s Georgia brigade, which had already been ordered to bolster the left, arrived just in time to meet Mower head-on as he neared the Smithfield Road. Simultaneously Hardee, in command of the Confederate left, appeared at the head of the 8th Texas Cavalry and promptly charged Mower’s left flank while Wheeler’s cavalry, moving up on the right of Hardee, drove a wedge between Mower’s brigades and the rest of the XVII Corps. Hampton assisted in the repulse of Mower by attacking the exposed right flank with another brigade of cavalry.

Forced to retreat from this nest of angry hornets, Mower fell back to the shelter of a ravine some distance to the rear, and when the fire slackened he again withdrew, this time to his original position. He had re-formed his lines and was about to renew the assault when orders arrived from Sherman to remain where he was and dig in. Offensive action ceased for the day.

Again both armies spent a wet, miserable night huddled in trenches and rude shelters, exposed to a driving rain that denied them even the comforts of a camp fire. Occasionally the flash of gunfire would illuminate the sky and reveal the position of the Union batteries, which lobbed shells into the Confederate lines. During the night Johnston learned that Schofield and Terry had reached Goldsboro and were within a day’s march of the battlefield. With nothing to gain and everything to lose by remaining cooped up at Bentonville, he ordered an immediate withdrawal. When Sherman’s skirmishers probed cautiously forward the next morning, they found only vacant works before them. A gesture was made to follow the retreating Confederates a few miles north of Mill Creek, but after burying the dead and removing the wounded, Sherman’s army went into camp near Goldsboro for rest and supplies. Later they moved on to Raleigh, and at the Bennitt House, a few miles west of Durham’s Station, Johnston on April 26 surrendered the remnants of his army.

Bentonville was the climax of Sherman’s Carolina campaign. By Civil War standards it was not a large battle. Sherman lost 1,527, most of them in the Left Wing, while Johnston suffered 2,606 casualties, a large number of whom were prisoners. Neither army won a clear-cut victory, and public attention soon focused on the more dramatic events that led to the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox.

Strategically the battle failed to prevent or even to seriously delay the fulfillment of Sherman’s objective—the occupation of Goldsboro, the consolidation of his forces there and the establishment of a new line of communications based upon the railroad to New Bern. Sherman’s main concern was supplies; he had nothing to fear from Johnston’s army unless the latter could catch one of his columns and defeat it in detail.

But was this likely, or even possible? By 1865, the American soldiers had become so adept in constructing fieldworks that it was a rare occasion when either side achieved a decisive victory. At Bentonville the Left Wing outnumbered Johnston’s whole army by some 10,000, and Slocum had only to dig in and hold on until help arrived. True, Carlin’s division was dispersed, and Morgan’s division might well have been destroyed but for the timely intervention of Cogswell’s brigade, but even with these two divisions routed, there remained the XX Corps plus four brigades that had been left to guard the wagon trains. It is inconceivable that this corps, posted behind strong earthworks and supported by both cavalry and artillery, could not have maintained its position until reinforced the following morning. One is forced to agree with Maj. Gen. Jacob D. Cox who, when informed by “rebel citizens” that Slocum had been whipped, noted in his journal, “We suspect that his advance guard may have received a rap, but know the strength of his army too well to believe that Johnston can whip him.” And even if the Left Wing were crippled as a fighting force, it would not have prevented Sherman from concentrating more than 60,000 troops at Goldsboro––a force much too large for Johnston to stop it from marching into Virginia.

Bentonville was a battle of subordinates. Sherman was not even present on the 19th. Slocum handled his reserves with skill, but the credit for stopping Johnston’s attacks properly belongs to Fearing, Cogswell and Morgan. Had it not been for the faulty judgment of another subordinate, Carlin, in selecting a defensive position in front of instead of behind a swampy watercourse, there might have been no cause for a retreat at all. Among the Confederates, Hampton and Hardee seem to have been the guiding spirits. Hampton selected the site and suggested the plan of battle, Hardee personally organized and led the Confederate charge on the 19th, and both were responsible for driving back Mower on the 21st. Bragg figured in two unfortunate decisions. By calling for reinforcements that were not needed he must bear the responsibility for delaying the Confederate attack against Carlin as well as for weakening it at its most decisive point, and by restraining Hoke from exploiting Hill’s breakthrough behind Morgan’s line, he may also have jeopardized the success of this attack.

As for the rival commanders, both are open to criticism. Johnston’s strategy was sound enough, but he lacked the numbers necessary for a decisive victory. Why he remained at Bentonville after Sherman’s army was united, however, is a mystery. He claimed that it was to evacuate the wounded, but this is scarcely a valid justification for the likely sacrifice of one of the few Confederate armies that remained intact. Yet he lingered with no apparent plan, and no right to assume that Sherman would repeat the mistake he made at Kennesaw Mountain. Whatever his reason, Johnston maintained his position with his usual skill, and his withdrawal was as masterly as any in his career.

To appreciate Sherman’s conduct, one must understand his method of waging war. Sherman was essentially a strategist, a master of maneuver and logistics. With him strategic considerations always came first, and in this instance Goldsboro, and not the enemy army, was his primary objective. He wished to shun a general engagement on the 20th because he was unwilling “to lose men in a direct attack when it could be avoided.” He had been criticized for recalling Mower, and it is probably true that had he supported his impulsive subordinate he could have won a great victory. But his opportunity was not as golden as it often is made to appear. Mower had actually retreated before receiving the order to withdraw, and had he been permitted to advance a second time, he would have found the Confederates heavily reinforced in his front. Sherman did not realize the extent of Mower’s penetration until the next day, when bodies of Union soldiers were found within 50 yards of Johnston’s headquarters. By counterattacking promptly with all available troops, the Confederates had created an illusion of strength. That it was not altogether illusory, however, is suggested by the Union casualty returns. Mower lost 149 men in this action—more than the entire XX Corps in the first day’s fighting.

Today Bentonville is one of the best preserved battlefields of the Civil War. Much of the forest has been cleared away, and Cole’s plantation is cut up into small farms, but in general the topography has changed little. Some breastworks and rifle pits have been plowed under, of course, but enough remain to enable the visitor to reconstruct the main course of the battle. Cole’s house was destroyed during the fighting, but the Harper House, which was used as a field hospital for both armies after the battle, was acquired by the state of North Carolina in 1957 and now serves as a museum. As a state historic site, the Bentonville Battlefield, ignored for nearly a century, has become a popular tourist attraction, which means fortunately that neither the battle nor its physical remains are any longer in danger of fading away.

It is appropriate that this should be so, for in the field near the Harper House, under a monument that until a few years ago was in a sad state of disrepair, lie 360 Confederate dead. They offer a perpetual reminder that Sherman did not pass by unchallenged.

Originally published in the January 2006 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.