‘The merit of this gentleman is certainly great and I heartily wish that fortune may distinguish him as one of her favorites.’

—George Washington

“NEVER SINCE THE FALL OF LUCIFER HAS A FALL EQUALED HIS,” Major General Nathanael Greene declared after Benedict Arnold had defected to the British in September 1780. The New Jersey Gazette called him “a mean toad eater.” The outrage was understandable, given that Washington had lost what he considered his best fighting general.

But there was far more to the man than his treasonous acts.

ARNOLD DESCRIBED HIMSELF AS “A COWARD” until he was “15 years of age,” when, as his family’s sole surviving son, he had to step forward and become the surrogate head of household. Apprenticed to a relative, he learned the apothecary trade and opened his own store in New Haven, Connecticut, in the 1760s, then broadened his businesses to include the West Indies trade and trade with Canada, often serving as captain of his own vessels. Despite legends to the contrary, on the eve of the Revolution he was a prospering merchant. He was also a military novice, a true amateur in arms.

Arnold was an enthusiastic and resourceful defender of American rights, and in 1774, smelling war with Britain brewing, he organized some 65 New Havenites into Connecticut’s 2nd Company of Footguards. After learning about the battles of Lexington and Concord, Arnold, the elected captain, prepared to lead the footguards to the Boston area. They had uniforms, paid for by Arnold, but lacked muskets, powder, and ball—all available in New Haven’s powder magazine. But the cautious town fathers, fearing the spread of a shooting rebellion, refused the footguards entrance. Arnold gave them a few minutes to rethink matters, then informed them that his company would force its way into the magazine. Intimidated, the town fathers handed over the keys. Within a few days, the well-armed footguards arrived outside Boston, joining the thousands of other New Englanders who were gathering to pin down Lieutenant General Thomas Gage and his redcoats in the city.

The rebel forces desperately needed armament, and Arnold met with Dr. Joseph Warren and other local rebel leaders to discuss the possibility of capturing the valuable cache of artillery pieces at Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point on Lake Champlain. In early May the Massachusetts Committee of Safety gave Arnold a colonel’s commission. His orders were to hasten west, recruit a regiment, and seize the lightly defended fort from the British.

Taking the fort, Arnold believed, would not be a problem as in its “ruinous condition,” it “could not hold out an hour against a vigorous onset.” But Arnold had not anticipated having to contend with Ethan Allen and Vermont’s Green Mountain Boys. The Vermonters, operating under apparent authority from Connecticut, were already in position to take the fort when Arnold, still troopless himself, caught up with them on the east bank of Lake Champlain in early May. Arnold displayed his commission, but the Green Mountain Boys, a rough-hewn lot, laughed at him. Allen was the only leader they would follow, especially since Arnold had no troops with him. Finally, after some shrewd negotiating by Arnold, Allen agreed to a joint command. Under cover of darkness, the two led a party across the lake and easily captured the fort with no loss of life on May 10, 1775.

TOO OFTEN, THROUGH THE PRISM OF TREASON, Arnold has been portrayed as an impulsive, needlessly confrontational military leader. In reality, he was often a master of patience and restraint, concentrating on the goals he wanted to achieve. Such was the case with Allen and the Vermonters. To Arnold, they were far from enthusiastic patriots determined to secure valuable ordnance pieces for the cause of liberty. He viewed them as frontier ruffians mostly interested in plundering whatever goods they could find in the fort. And in fact, once inside the fort, the boys discovered some 90 gallons of rum, and after getting drunk, repeatedly belittled Arnold; two of them apparently took pot shots at him. But Arnold showed impressive forbearance and waited until the boys drifted back across the lake to Vermont with their plunder.

Concerned that a British counterforce might come down from Canada to retake the fort, Arnold seized the initiative. In mid-May he took a captured schooner and two bateaux up Lake Champlain and 25 miles into Canada, striking the British stronghold of St. John. He and his raiders seized small weapons and two 6-pounder cannons, destroyed any small craft they could find, and sailed away in a British sloop the Americans later named the Enterprise. By this one aggressive stroke, Arnold had taken command of the lake.

A month later Arnold sent a letter to the Continental Congress, advocating the invasion of Quebec Province. Having sailed his own trading vessels into Quebec and Montreal,

Arnold understood the terrain, and he accurately predicted British strategy: They would attempt to surround New England and cut off the head of the rebellion. By seizing Quebec Province, the patriots could disrupt that move and at the same time assure “a free government” fully dedicated to liberty in Quebec. Also, in the event of a long war, Canada could serve as “an inexhaustible granary.” Arnold closed his letter by laying out an operational invasion plan he insisted should be implemented “without loss of time.” He offered to take command of the proposed expeditionary force, confident that “the smiles of heaven” would soon be blessing the patriot cause.

Arnold’s energy on the wilderness trek earned him the epithet ‘America’s Hannibal’

The Congress liked Arnold’s plan but did not name him commander. As events played out, overall command of the invasion through Lake Champlain went to Congress’s designated Northern Department commander, wealthy Philip Schuyler of New York. Schuyler, though, rated Arnold’s performance in taking Fort Ticonderoga as fully meritorious, and he and others commended the young soldier to George Washington. Meeting with Arnold, Washington too saw merit in the enthusiastic young patriot.

Arnold accepted Washington’s offer of a colonel’s commission and the assignment to lead one of two patriot forces into Canada. The first detachment, under Schuyler, headed north down Lake Champlain. When Schuyler fell ill, command moved to Brigadier General Richard Montgomery. Meanwhile, Arnold’s column had to struggle through the backwoods of Maine. Arnold’s personal stamina and boundless energy on the wilderness trek earned him the epithet “America’s Hannibal” and a brigadier generalship.

By mid-November Montgomery’s force had captured Montreal, while Arnold’s contingent, after much suffering, had reached the Plains of Abraham outside the walled city of Quebec. In December the two detachments joined forces, and under cover of a driving blizzard on the last day of 1775, attempted to breach the city gates. The plan of attack, Arnold knew, was impetuous and born of desperation: With the enlistment periods of patriot soldiers ending with 1775, Arnold and Montgomery felt they had no choice but to attack before some portion of their force disappeared into the woods and returned to New England.

Montgomery, heading one column, was killed instantly by a cannon blast; Arnold, heading a second, sustained a nasty wound to his left leg that knocked him out of the assault. Before the fighting was over, dozens of patriots lay dead or wounded and over 400 had been taken prisoner by the British.

But Arnold refused to quit. As his badly wounded leg began to heal, he mounted a paper siege of sorts around Quebec with the few troops he had left. He spent the winter season, as he wrote, laboring “under almost as many difficulties as the Israelites of old, obliged to make brick without straw.” Arnold even drew up plans to break into the walled city, but he lacked the necessary resources to do so. In the end, despite an ennobling effort by Congress to send more troops to Canada, Quebec Province could not be held. British and Hessian reinforcements began arriving at Quebec City during May 1776. By late June they had driven the patriot forces, now riddled with smallpox and other diseases, all the way back to Fort Ticonderoga.

ARNOLD WAS AMONG THE LAST REBELS TO LEAVE Canadian soil. He was among the first to think through operational plans to block the British military assault that was sure to come out of Quebec Province. By June 1776 that invasion was underway. Given the limited size of most 18th-century military forces, British numbers, including Hessians, were impressive. By early August some 45,000 soldiers and sailors were gathering around Manhattan Island to capture and establish it as their main base of operations; another 8,000 were preparing to move out of Canada and crush patriot forces in the northern theater. By midsummer, Quebec’s Governor Carleton, with Major General John Burgoyne serving as his second in command, was assembling a flotilla of vessels to move his army into Lake Champlain, then south along the Hudson River Valley.

From Arnold’s perspective, the key was to block Carleton or, better still, to drive the advancing enemy back into Canada. Arnold worked closely with Schuyler, who functioned as the key supply officer, and with Horatio Gates, a former British field grade officer who had become a major general in the Continental army. At Schuyler’s request, Arnold agreed to serve as commodore of the rebel fleet being assembled on Lake Champlain. His first priority was to oversee the construction of enough new vessels to put on a show of defiance that might deter the expected British onslaught. Given the shortage of skilled ships’ carpenters and of such essential supplies as cordage, sailcloth, and various kinds of cannon shot, it was a daunting task.

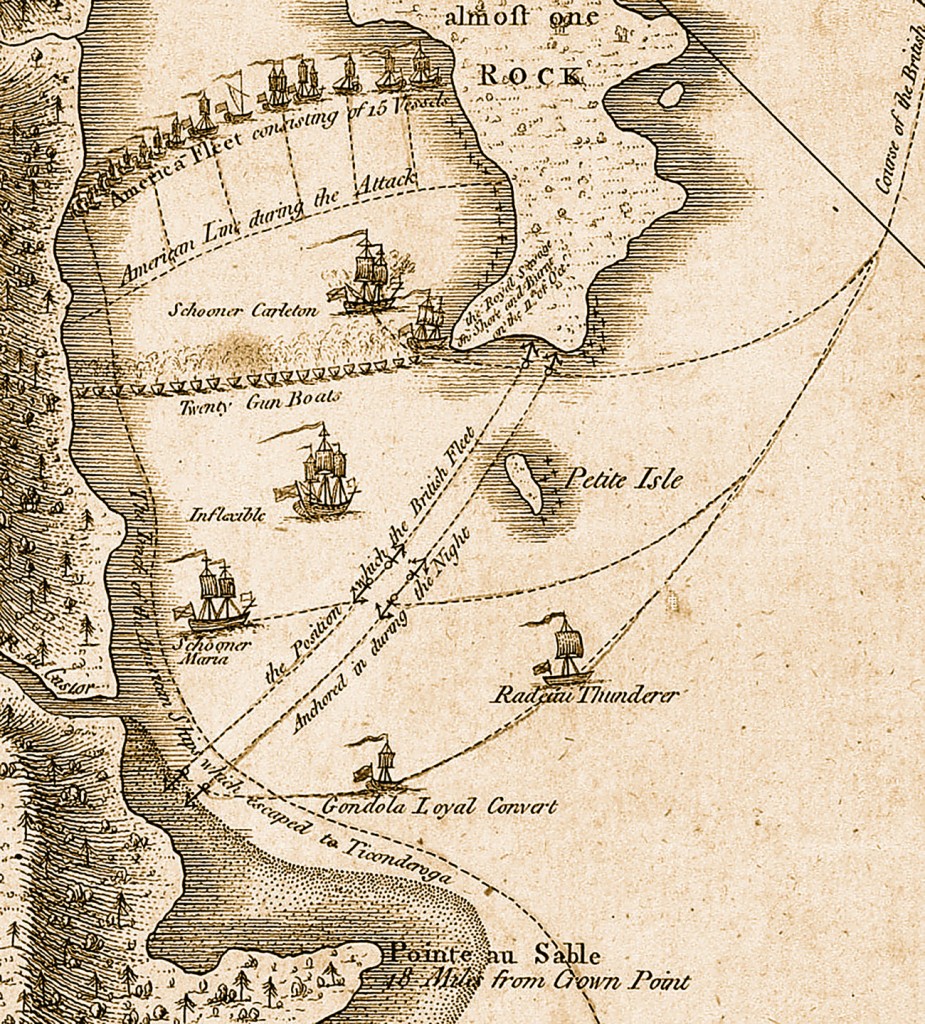

Nevertheless, by mid-September Arnold was sailing north toward the Canadian border with nine flat-bottom, fixed-sail gundalows, each with the capacity to carry up to 45 men and a few ordnance pieces. The gundalows could only sail before the wind, not maneuver to windward. In addition, the fleet included the sloop Enterprise that Arnold had captured in 1775 and three schooners; one of them, the Royal Savage, had been taken from the British during Montgomery’s advance into Canada. Later, three new row galleys—the Trumbull, Washington, and Congress—joined the flotilla. Arnold had pushed for the construction of these larger two-masted craft, with lateen sails that could swivel with the wind.

Arnold was ordered to conduct a defensive war and to take “no wanton risk” with the fleet, yet he was to display his “courage and abilities” in “preventing the enemy’s invasion of our country.” In other words, he was not to conduct offensive operations, such as sailing into Canada and attacking the British fleet then being assembled at St. John. Rather, he was “to act with such cool, determined valor, as will give them [the enemy] reason to repent their temerity” in moving on Fort Ticonderoga.

Arnold believed his only hope for retarding the British advance was to innovate, and innovate he did. Arriving near the Canadian border in mid-September, he feinted continuing north on the Richelieu River to St. John. He hoped scouting reports about the fleet’s presence and its seeming readiness for combat would reach Governor Carleton. During Arnold’s paper siege of Quebec City, he had sized up Carleton as a cautiously calculating leader, who would not take unnecessary risks, even when he held the military advantage. As Arnold had anticipated, the rebels’ bold appearance near the Canadian border caused Carleton to delay three critical weeks, giving the patriots more time to strengthen defenses at Fort Ticonderoga.

Finally, on October 4, Carleton ordered his flotilla to move out. He had been waiting for the completion of the Inflexible, a sloop of war whose 18 12-pounder cannons gave it firepower superior to that of any vessel available to Arnold. Carleton’s objective was to sweep aside what he called the “considerable naval force” waiting to defend Lake Champlain and to retake Crown Point and Fort Ticonderoga before winter weather halted further operations.

ARNOLD HAD 16 VESSELS TO CARLETON’S 36, which included 28 gunboats—smaller craft that each carried one sizable cannon (12 to 24 pounders). With 417 artillery pieces in all, the British held a more than four-to-one advantage in firepower, since Arnold’s fleet mounted only 91 cannons, including small swivel guns. To make matters worse, his crews comprised mostly soldiers and few sailors, whereas the British crews were full of experienced mariners. Despite the disadvantages, Arnold knew that he would have to resist the powerful flotilla, because Fort Ticonderoga did not have the supplies of powder and ball necessary to stand up to a sustained British onslaught.

Arnold wanted to position his force in a location that would both surprise the enemy and neutralize Carleton’s crew and firepower advantages. While cruising down Lake Champlain toward Canada, Arnold had spotted Valcour Bay along the New York shoreline. To any fleet moving south, the half-mile-wide bay was hidden by Valcour Island, which rose 180 feet. By late September Arnold had nestled his fleet inside the bay in a half-moon formation. “Few vessels can attack us at the same time,” he explained, “and those will be exposed to the fire of the whole fleet.”

The morning of October 11, 1776, Carleton’s vessels, riding a crisp northerly wind, rounded the eastern side of Valcour Island, heading for Fort Ticonderoga some 70 miles away. About two miles south of the island the British finally spied the waiting Americans and hauled into the wind. That broke up their fleet’s formation, and the battle ensued as Arnold had predicted. The British flotilla, trying to maneuver against the wind, could not form into an organized battle line, so though the patriots sustained serious damage to their vessels and many casualties, their fleet was still functional when nightfall ended the fighting.

Though the British, too, had suffered losses, Carleton believed that as soon as the wind swung to the south, his flotilla could move in and finish off the rebels trapped in the bay. But as evening approached, Arnold and his captains saw that the British had left a small opening close to the New York shoreline. Taking advantage of a heavy fog, the patriot vessels formed into a single line and with muffled oars rowed through the gap. When the fog lifted the next morning, an astonished Carleton found an empty bay.

The race south was on, and on October 13 the British caught up to the damaged, slow-moving American vessels about 30 miles up the lake, near a landform called Split Rock. Here Arnold, conscious that there were still munitions shortages at Fort Ticonderoga, precipitated one of the most daring fighting moments of the young Revolution. Aboard the row galley Congress, he ordered his fleet to turn north and attack the swarming enemy vessels. For something like two hours, he and his crew engaged in close-quarter combat with three of Carleton’s vessels. The British held a fivefold advantage in firepower over the rebels, and that advantage was exacerbated when four more British craft joined in the pounding.

After two hours Arnold’s flagship, with “sails, rigging, and hull…shattered and torn to pieces,” limped away and into a small bay in Vermont territory, along with the four torn-up gundalows it was protecting. Wanting to leave nothing that the enemy might find useful, Arnold ordered all five vessels set on fire before he and his crew made their way overland, reaching Ticonderoga the following day.

Amazed at the fighting spirit of the patriots, Carleton moved his forces up to Crown Point, but then he hesitated. Burgoyne’s land force was ready to take on Fort Ticonderoga, but Carleton began to fret about supply lines back to Canada, especially with winter looming. He was no longer sure he could capture Fort Ticonderoga without grave results, possibly even defeat. So in early November the governor decided to withdraw his entire force and wait out the winter before launching another invasion in 1777. Arnold’s bravado had helped precipitate the pull-back—it was a reversal of what the governor had observed earlier that year, when patriots pulled out of Canada.

Arnold’s military brilliance and daring had helped save the patriot cause in the northern theater—at least for another year. Members of the Continental Congress called him a true hero, but demeaning voices were also raised. From Ticonderoga, Brigadier General William Maxwell, himself devoid of martial accomplishments, labeled Arnold “our evil genius to the north.” According to Maxwell, Arnold was motivated solely by personal aggrandizement, and his “pretty piece of admiralship” had wasted the patriots’ Champlain fleet. Others, assessing Arnold’s actions in 1776, disagreed: More than a hundred years later, the naval historian Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote in his classic The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783: “The little American navy on Champlain was wiped out; but never had any force, big or small, lived to better purpose or died more gloriously, for it saved the Lake for that year.”

Soon after that event Arnold would again provide invaluable service to the American cause. His vision and battlefield courage resulted in the defeat and capture of John Burgoyne’s invading army at the critical Battle of Saratoga.

DESPITE BEING AN AMATEUR IN ARMS in the first years of the Revolution, Arnold established himself as a fighting general and commodore, who tenaciously outwitted superior enemy forces. But it was his treachery in the last years of the war, not his natural military genius, that earned him an accursed place in the pantheon of American military leaders.

James Kirby Martin is Cullen University professor of history at the University of Houston and the author of many books, including Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered.