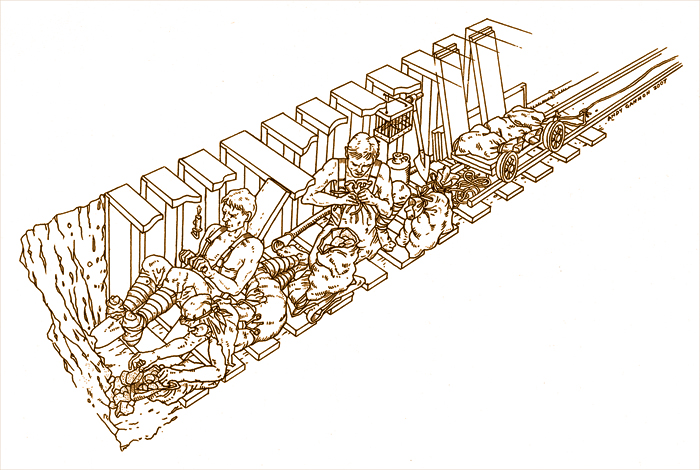

They were an underground army to themselves. Leading the way were soldiers known as “clay-kickers,” who leaned back on inclined boards and kicked spades into the heavy French soil, carving it out inch by inch. Following on their bootheels were the “moles,” who enlarged each cavity. Finally came munitions experts, who carefully packed the chambers with explosives. Together, the tunnelers toiled beneath the Western Front fields of Flanders.

At the outset of World War I in early August 1914 the Germans invaded Belgium and quickly pushed through to France. The Allies were able to halt their advance a month later at the First Battle of the Marne, after which the conflict settled into a disastrous stalemate that would claim millions of lives. Combined casualty estimates at First Marne alone approached a half-million. The combatant armies then dug in along a meandering line of fortified trenches stretching some 440 miles from the North Sea to the French-Swiss border.

Each side resorted to creeping artillery barrages followed by massed infantry attacks. Soldiers entering the shell-pocked no man’s land in between faced enemy trench lines bristling with barbed wire and swept by interlocking fire from machine gun nests. Territory was gained, lost, regained, then fought over again. No new technology—aircraft, flamethrowers, poison gas, tanks, etc.—provided enough of an advantage to break the deadlock. There was little hope on either side. But one tactic, used to varying effect in previous wars, did produce results on the Western Front—tunneling and mining.

In December 1914 German soldiers dug shallow tunnels that stretched beneath no man’s land to the British lines near Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée, France. On the morning of December 20, having placed 10 mines—each weighing 110 pounds—beneath the Sirhind Brigade of the 3rd (Lahore) Division, the Germans detonated the explosives, following up with an immediate infantry attack that advanced some 300 yards and inflicted heavy casualties on the British Indian forces.

Two months later British Maj. John Norton-Griffiths, a successful civil engineer then busying himself on the home front, received a telegram instructing him to report to the British War Office. A Conservative member of Parliament known to colleagues as “Empire Jack,” Norton-Griffiths was a dyed-in-the-wool imperialist, a colorful aristocrat and something of a maverick. History records him as “handsome, physically imposing, and with the strength and endurance of a prize fighter…a charming swashbuckler and a persuasive showman,” one of the “most dashing men of the Edwardian era,” but also a man of “fiery temperament, a rebellious nature and uncontrollable rages.” Tellingly, he was also known as “Hellfire Jack.”

Before the war Norton-Griffiths had founded an engineering company, soon earning a global reputation for construction projects that required tunneling through clay subsoil—from railways in Angola and Australia, to harbors in Canada, to drainage systems in Manchester and Liverpool. Given the similar soil conditions in Flanders, Norton-Griffiths believed his clay-kickers, digging in areas too confined for pickaxes, could tunnel faster, quieter and—perhaps most important—deeper than the Germans. Weeks before the German attack near Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée he’d sent a letter to the British War Office, proposing to organize such a unit. It had gone unanswered.

Then came the February 1915 summons. In a private meeting with Lord Kitchener, Britain’s iconic secretary of state for war, Norton-Griffiths impulsively grabbed a coal shovel from a fire grate in the office and dropped to the floor to demonstrate the digging technique. Kitchener promptly asked his exuberant guest to cross the channel and explain his proposal to Allied commanders in France.

After several briefings and similar demonstrations, engineer in chief Brig. Gen. George Henry Fowke agreed to the plan, and Kitchener duly authorized the formation of special tunneling units composed of English, Welsh and Scottish coal miners, Cornish tin miners, and diggers from Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Fowke put Norton-Griffiths in charge, gave him carte blanche and sent him to the front as a liaison to Col. Robert Napier Harvey, assistant to the engineer in chief.

Norton-Griffiths was soon touring the British lines in his wife’s borrowed Rolls-Royce Landaulette, bearing crates of fine port with which to cajole field officers into releasing men suited to his mission. Recruiting those who had worked in engineering companies before the war, the major explained their task would be “a simple one”—to dig beneath the German lines, plant explosives, wire up the charges, return to the Allied trenches and watch the Germans “go up.”

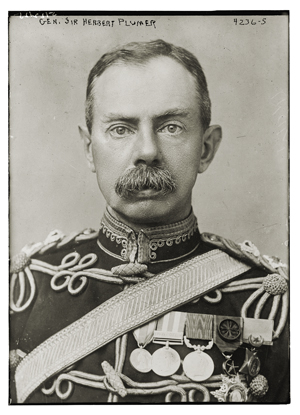

The British had long considered a major offensive in Flanders, and by early 1916 Second Army commander Gen. Herbert Plumer began planning for such an attack. A necessary precursor of the plan was to capture Messines Ridge, on the southern arc of the Ypres salient, the low-lying clay plain that had been the site of several major offensives. The Germans had held the ridge since November 1914 and heavily fortified it against infantry attacks. Sensing an opportunity, Norton-Griffiths put his men to work in an all-out tunneling effort.

For the miners digging the shafts—posted with Deep Well signs to preserve secrecy—the work was tedious and dangerous. The tunnels were dark, small and often flooded. There was always the possibility of a cave-in, and diggers also feared seeping carbon monoxide from burst enemy artillery shells and methane buildup from the earth itself. In cold, cramped conditions the miners labored in four- to eight-hour rotating shifts. Given their state of near constant fatigue, they were prone to illness, with especially high rates of trench foot, a painful condition caused by prolonged immersion in cold water or mud.

“It was stuffy, filthy, oppressive, dangerous—just…frightful,” recalled Pvt. Donald Hodge. “You were down there on your hands and knees for hours on end, part of a long line of men passing bags back between our legs.…It was the most tiring and painful work I ever did on the Western Front.”

During rest periods from such backbreaking tasks, the men employed a range of listening devices to pinpoint their enemy counterparts. On occasion miners accidentally broke through into German tunnels, or vice versa, sparking desperate hand-to-hand combat. Other times the tunnelers would simply blow the enemy works. Miraculously, despite all such obstacles, the operation remained undetected. Finally, in June 1917, having burrowed for some 18 months, the tunnelers finished their work.

Unfortunately for Norton-Griffiths, he couldn’t be there for the big finale. In late 1916 the War Office had tapped him to lead another intrepid group set on sabotaging the oil fields in Ploesti, Romania. There his men dumped cement down the wells, filled oil tanks with nails, emptied storage wells and set them ablaze. Norton-Griffiths’ team destroyed some 70 refineries and 800,000 tons of crude oil, creating shortages from which the Germans never fully recovered.

Meanwhile, back in Belgium “Hellfire Jack’s” munitions experts packed more than 500 tons of explosives beneath German positions along a 10-mile arc of the Messines Ridge, from dominating Hill 60 in the north to Trench 122 near Ploegsteert Wood in the south. Some tunnels stretched more than 2,000 feet long, and they delved as deep as 138 feet below the surface of the ridge.

The corresponding infantry attack, code-named Magnum Opus, was set for June 7, with “zero hour” at 3:10 a.m. The day before Second Army headquarters briefed the press on the forthcoming action. After the briefing Maj. Gen. Charles Harington Harington, Plumer’s chief of staff, was asked if it might alter the course of the war.

“I do not know whether or not we shall change history tomorrow,” Harington replied in dry British fashion, “but we shall certainly alter geography.”

In the weeks before the assault British battalions were moved forward, and captured Germans provided vital intelligence on their units’ preparedness. Preliminary bombardment of the enemy lines—with 2,266 field pieces and 428 heavy mortars—began on May 21. All firing ceased at exactly 2:50 a.m. on June 7.

The silence must have been deafening for Capt. Oliver Holmes Woodward. A metallurgist and mine manager who had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force, Woodward had been posted to a company of his nation’s newly raised Mining Corps. In November 1916 his 1st Australian Tunneling Company had taken over digging operations for the two northernmost mines at Messines, planting 53,500 pounds of explosives beneath Hill 60 and another of 70,000 pounds under an adjacent feature dubbed the “Caterpillar.” South of Woodward’s position that morning 17 other mines lay wired and ready to blow, each containing a potent mix of ammonium nitrate and aluminum powder known as ammonal. The mines ranged in weight from 14,900 pounds to a whopping 95,600 pounds. Their tandem detonation would signal the start of the Battle of Messines.

Woodward was tasked with triggering his team’s mines. “At 2:25 a.m.,” he later wrote, “I made the last resistance test and then made the final connection for firing the mines. This was rather a nerve-racking task, as one began to feel the strain and wonder whether the leads were properly connected up.…Breathlessly we watched the minute hand crawl towards the [appointed time], then, with white faces, we strained our eyes towards the enemy line, which had become visible in the gray dawn.”

The nail-biting silence persisted another 20 minutes, as Woodward and fellow miners along the line checked their watches, and 80,000 infantrymen stood ready to attack the ridge. Brig. Gen. Thomas Lambert was present in the Australian firing dugout and provided the countdown. “The general,” Woodward recalled, “in what seemed interminable periods, called out, ‘Three minutes to go—two to go—one to go—45 seconds to go—20 seconds to go’—and then, ‘9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1—FIRE!’”

‘I do not know whether or not we shall change history tomorrow,’ Maj. Gen. Charles Harington Harington replied in dry British fashion, ‘but we shall certainly alter geography’

“Suddenly, all hell broke loose,” one tunneler recalled. “It was indescribable. In the pale light it appeared as if the whole enemy line had begun to dance, then, one after another, huge tongues of flame shot hundreds of feet into the air, followed by dense columns of smoke, which flattened out at the top like gigantic mushrooms. From some craters were discharged tremendous showers of sparks rivaling anything ever conceived in the way of fireworks. The whole scene was majestic in its awfulness. At the same moment every gun opened up, the din became deafening and then nothing could be seen of the front but the bursting of our barrage and the distress flares of the enemy.”

“Our trench rocked like a ship in a strong sea, and it seemed as if the very earth had been rent asunder,” Pvt. Albert Johnson recalled. “What the Germans thought of this is better described without words.”

The earth at Flanders shook for 19 seconds in what comprised the largest man-made explosion to that date. As columns of flame shot high into the sky, pieces of concrete pillboxes—and their occupants—rained down for hundreds of yards in all directions. The blast sandwiched shut surrounding German trenches, instantly entombing soldiers where they stood, sat or slept. Witnesses recalled clods of earth the size of houses hurtling through the sky. French geologists at Lille University, 12 miles to the southeast, mistook the tremors for an earthquake, while reports in the London papers the next morning claimed Prime Minister David Lloyd George was among those across the channel who had heard the explosion.

The massive June 7 blast instantly killed an estimated 10,000 German troops. Another 7,200, many in shock and too disoriented to act, were captured in the attack that followed. The joint detonation of more than 900,000 pounds of ammonal had erupted into what one German survivor poetically described as “gigantic roses with carmine petals.”

Amid the haze of a creeping artillery barrage came the massed infantry assault by nine divisions of Plumer’s Second Army. The advancing troops took their initial objectives within two hours and captured the ridge within a day. Reserves from British Gen. Hubert Gough’s Fifth Army and the French First Army under Gen. François Anthoine reached their respective final objectives by mid-afternoon. By June 14 the Messines salient was solidly in Allied hands. The limited offensive was as near a complete victory as could be imagined.

“Messines is to the tunneler what Waterloo was to Wellington,” British Capt. W. Grant Grieve wrote in the wake of the battle. “Never in the history of warfare has the miner played such a great and vital part in a battle.”

Despite the successful outcome, Messines was only the prequel to the broader Third Battle of Ypres (aka Battle of Passchendaele), which began on July 31 and continued through early November. That offensive reverted to form, with small gains for the Allies at great human cost, the British suffering some 310,000 casualties, the Germans about 260,000. The war itself dragged on another year. By the time the signing of the Treaty of Versailles formally ended the global conflict, as many as 19 million people—soldiers and civilians—had been killed or died from starvation or any number of illnesses.

John Norton-Griffiths, the man who had masterminded the mining operations along Messines Ridge, was knighted after the battle, promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1918 and created a baronet in 1922. He spent the postwar years in Egypt, overseeing a project to heighten the Aswan Dam. It proved problematic, threatening financial ruin and possible criminal prosecution. On Sept. 27, 1930, Norton-Griffiths hired a surfboat from his Alexandria resort, rowed offshore and promptly went missing. Searchers later found his body slumped in the bottom of the drifting boat, a bullet wound in the temple. The talented 59-year-old engineer and heralded veteran of the Western Front had died by his own hand. MH

New York–based Norm Goldstein is a regular contributor to Military History. For further reading he recommends Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers’ War, 1914–18, by Peter Barton, and Messines Ridge, by Peter Oldham.