In October 1907 U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt set out on a hunting trip in the northern Louisiana canebrake country near Tensas Bayou. There was nothing particularly remarkable about the president’s love of “manly sport” with rifle. He was among the most celebrated hunters in North America. Local politicians and press reporters vied with one another for the opportunity to meet and accompany the nation’s chief executive on his outdoor excursions. One member of the hunting party, however, was quite remarkable. Roosevelt’s handlers had specifically sent word they wanted the services of a legendary big-game hunter known for his personal idiosyncrasies as much as for his peerless tracking and hunting abilities.

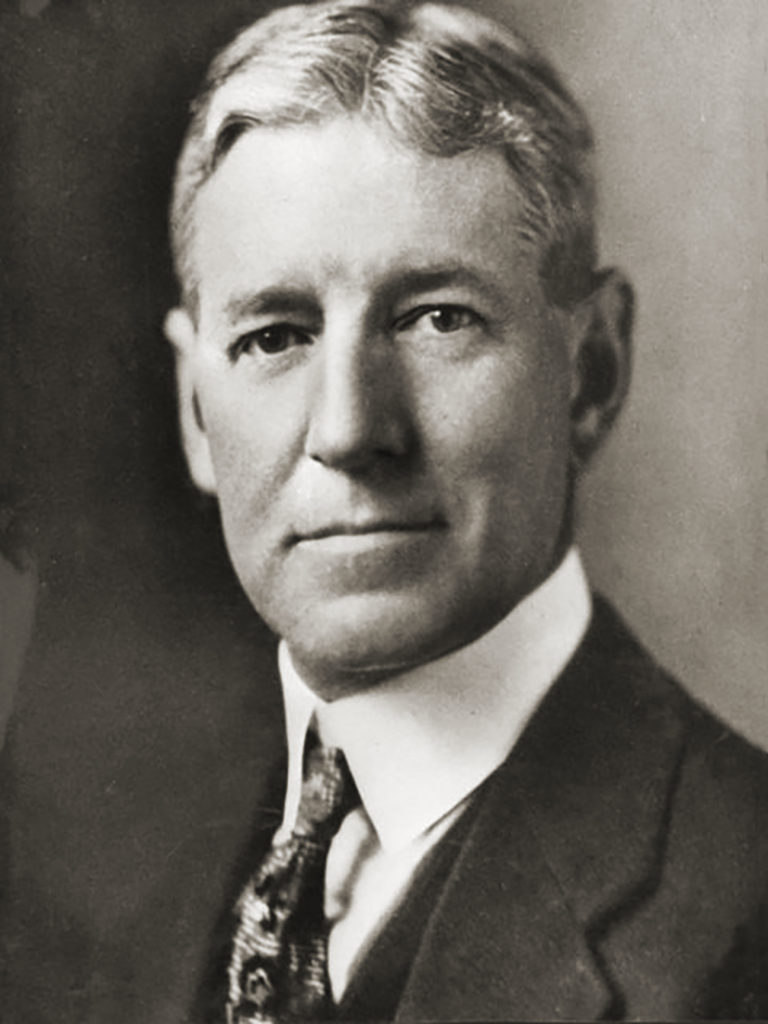

In appearance the man looked somewhere between 30 and 40 years old, though in fact he was over 50. A long beard covered the lower half of his face, and his luminous but sorrowful blue eyes coolly appraised all wildlife sign in his path. In an article about the hunt Roosevelt wrote for the newspapers, he shared this vivid description of his tireless guide:

“Ben Lilley [sic], the hunter, [was] a spare, full-bearded man with mild, gentle blue eyes and a frame of steel and whipcord. I never met any other man so indifferent to fatigue and hardship. He equaled Cooper’s Deerslayer in woodcraft, in hardihood, in simplicity—and also in loquacity. The morning he joined us in camp, he had come on foot through thick woods, followed by his two dogs, and had neither eaten nor drunk for 24 hours; for he did not like to drink the swamp water. It had rained hard throughout the night, and he had no shelter, no rubber coat, nothing but the clothes he was wearing, and the ground was too wet for him to lie on; so he perched in a crooked tree in the beating rain, much as if he had been a wild turkey. But he was not in the least tired when he struck camp; and, though he slept an hour after breakfast, it was chiefly because he had nothing else to do, inasmuch as it was Sunday, on which day he never hunted nor labored. He could run through the woods like a buck, was far more enduring and quite as indifferent to weather, though he was over 50 years old. He had trapped and hunted throughout almost all the half century of his life, and on trail of game he was as sure as his own hounds. His observations on wild creatures were singularly close and accurate. He was particularly fond of the chase of the bear, which he followed by himself with one or two dogs; often he would be on the trail of his quarry for days at a time, lying down to sleep wherever night overtook him; and he had killed over 120 bears.”

The man’s name was Ben Lilly, and he may have been the greatest big-game hunter ever to have lived in North America.

According to biographer J. Frank Dobie, Lilly was born on New Year’s Eve 1856 in Wilcox County, Ala., of Scottish ancestry. At a time when education for females was almost unheard of, Lilly’s mother was a graduate of Mississippi’s Nicholson Female College and later taught astronomy there as a faculty member. Lilly’s six siblings included a college professor and a pipe organist. Ben gravitated toward the inclinations of his male ancestors, who had fought in the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 and were skilled blacksmiths. Lilly himself gained renown as an expert knifesmith, forging and tempering his own blades (his favorite liquid for cooling steel was panther oil, which he claimed made his blades stronger).

Despite his mother’s best efforts to give him a proper education, Lilly drifted away from the military academy in Jackson, Miss., to which he’d been sent and lost touch with his family for a time. Ben’s Uncle Vernon Lilly eventually stumbled across his truant nephew running a blacksmith shop in Memphis, Tenn. He convinced Ben to move in with him on his cotton farm in Morehouse Parish, La., promising that if the young man did so and helped with the chores, he would inherit everything on the uncle’s death. Within a year Uncle Vernon kept his promise.

The Lilly farm centered on 300 acres of fenced cropland, outside of which sprawled great swaths of untilled swamp and canebrake. Ben never showed any particular enthusiasm for cotton farming, and the surrounding wilderness increasingly drew him away from his work. He quickly mastered the geography, demonstrating a unique ability to find his way through the most tangled and seemingly inaccessible areas. Acquaintances from that period of his life shared many stories of the young man’s nascent trail-finding and tracking abilities.

Lilly married in 1880, but the union was strained from the beginning. The death of the couple’s young son ended any hope of marital bliss, and they split up. Ben remarried in 1891, but by then he’d begun to spend more and more time away from home, penetrating ever deeper into the wild woods and swamps and seldom returning home unless to reprovision or repair gear. He kept his family—which grew to include two daughters and a son—fed and sheltered with profits from cattle trading, but he refused to be tied to a particular place. He resolved always to be available if the urge to hunt came over him, and he would often stop whatever he might be engaged in at the time to answer the call. Hunting, to him, was almost a religious vocation.

Unlike contemporary bear hunter turned bear conservationist William H. Wright, Lilly never seemed to lose his appetite for hunting and killing bears, mountain lions and other apex predators. While such a position runs counter to present-day politically correct sensibilities regarding game and trophy hunting, Lilly couldn’t be bothered. For one, the opinions others held of him didn’t keep him up at night. For another, he never saw wild animals in any other light than as a challenge for his tracking abilities or an enemy to be exterminated. He was,

for better or worse, a man of his time.

Lilly was also a devout Christian who would never work on a Sunday. If the Sabbath arrived in the midst of a hunt, he would cease all activity and make camp wherever he was. On such occasions, if he lacked fresh meat, Lilly would reach into his provisions bag and pull out an ear of corn for roasting. Such simple fare comprised his diet for weeks at a time. He was also a noted teetotaler, did not smoke and would not even drink coffee, presumably because of the caffeine. The hunter always had a Bible at hand and was well versed in Scripture.

Various witnesses attested to Lilly’s strict adherence to his beliefs. New Mexico rancher Bela Birmingham recalled one especially memorable encounter with the peripatetic hunter. One brisk fall evening while moving horses between pastures in preparation for winter, Birmingham and his brother-in-law made camp, built a fire and set about preparing dinner. They became aware of Lilly’s presence when his pack of hounds sounded close by, apparently hot on the trail of game. Lilly soon hove into view. He was tracking a mountain lion, the hunter explained, but since it was late on a Saturday evening, he would postpone the hunt till Monday, as he never hunted on Sundays.

The ranchers were well supplied with beef, and after Lilly volunteered he hadn’t eaten in two days, they made him supper. He promptly wolfed down three big steaks and six or seven sourdough biscuits. Rising early on Sunday morning, the scruffy hunter cut a hole in a nearby ice-covered pond and jumped in wearing his long underwear—the outdoorsman’s version of a bath.

Bright and early Monday morning, Lilly resumed his pursuit of the mountain lion. By the time the ranchers caught up with him later that day, the hunter had bagged two large lions, including the one he’d been after on Saturday. When Birmingham mentioned having lost his watch somewhere along the trail that morning, Lilly offered to backtrack, locate the missing timepiece and bring it by the ranch house that evening. Birmingham’s route home was long and circuitous. By the time he arrived, he found Lilly and his brother-in-law eating dinner and his watch waiting on the table. Lilly said he’d found it a few feet from the tracks of Birmingham’s horse soon after setting back. His remarkable 48-hour display of hunting, discipline, tracking and route-finding duly impressed both ranchers.

Throughout his eccentric life Lilly honed his knifesmithing skills, earning repute as much for the creations of the forge as for the trophies of the hunt. A good knife remains an important tool when hunting in the oft tangled wilderness where big-game animals dwell. According to biographer Dobie, Lilly took pleasure in presenting well-made knives to friends or people he admired. One peculiarity of his knives was that both sides had a sharpened edge. Lilly had come to close grips with bears and believed it of utmost importance that a knife be able to cut in any direction. He also corkscrewed the blades of some knives for easy removal.

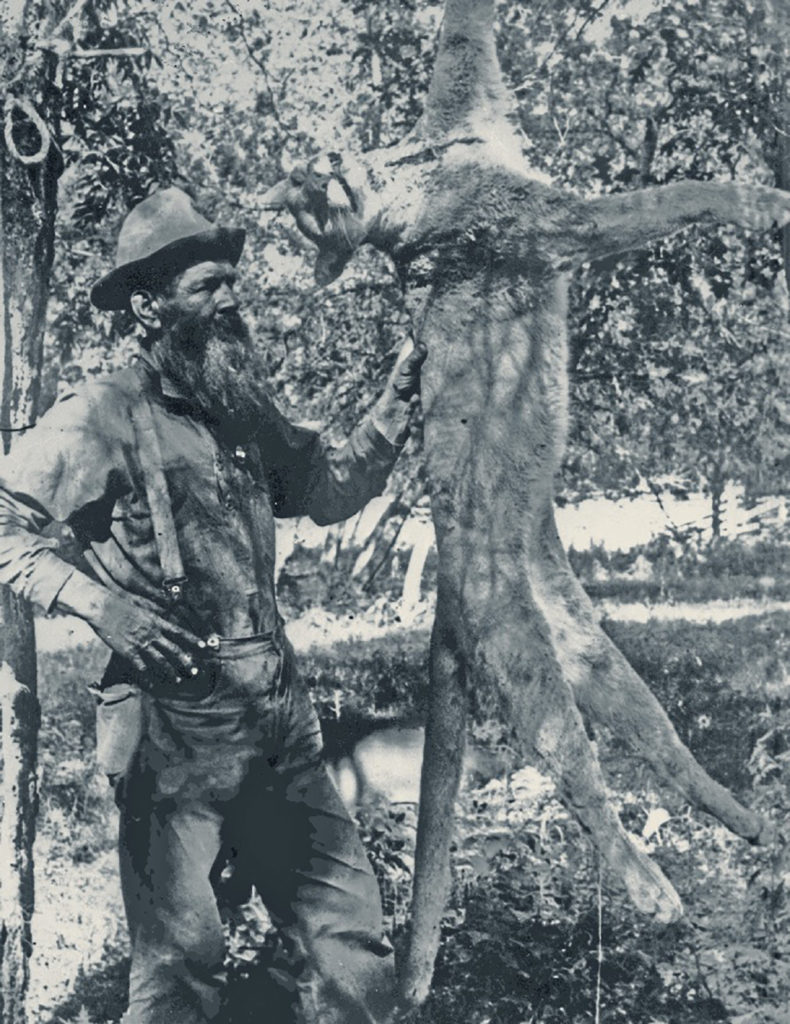

The hunter owed his life to one such specially crafted knife. In April 1913 in Arizona’s snowbound White Mountains 56-year-old Lilly ran across sign of a large grizzly. Setting out with a rifle, light gear, no food and a hound tied off on his waist, he tracked the bear for three days, managing to hit it several times with distant rifle shots, but unable to make a killing shot. He continued to follow its tracks and blood trail in deep snow until the bear suddenly appeared, almost ending Lilly’s career on the spot. “Then, right in front of my body, 15 feet away, the bear popped out, charging me,” the hunter recalled. “My first shot hit him center in the breast; that checked him. My second shot was under the eye, about 3 feet away. He fell against my side. I was bogged in snow waist deep. I couldn’t see the bear’s head. He seemed to be drawing deep breaths. I fired another shot for his heart. I was wearing a knife 18 inches long. I drove it for the heart. That finished him.”

In addition to his famed service as a guide for President Roosevelt, Lilly made headlines guiding a 1921 bear-hunting excursion for Oklahoma oil tycoon W.H. McFadden. McFadden spared no expense for his elaborate, monthslong hunt through the Rocky Mountains from Mexico to Canada. Regardless, Lilly avoided the well-equipped camp and its accompanying creature comforts, preferring his usual ascetic ways. He tried his best to corner a trophy grizzly for his client to shoot, but McFadden’s frequent absences from the party for business reasons sidelined him from the pursuit at several key junctures. The bear ultimately went into hibernation, Lilly left the party, and McFadden came up empty. The failed excursion represents perhaps the only bear that ever escaped the relentless efforts of the master tracker and hunter. Not that Lilly was to blame; McFadden was simply not as dedicated to the pursuit as his 64-year-old guide.

Lilly seemed to find his greatest personal satisfaction hunting down and killing apex predators (bears, wolves, mountain lions, etc.) on behalf of various ranchers in the Southwest and, later, for the U.S. Biological Survey and U.S. Forest Service. Western ranchers and stock growers had complained to the U.S. government for decades about the losses such predators inflicted on their cattle herds and sheep flocks. The government responded by offering generous bounties for the skulls and hides of these animals. State and local officials and private ranchers often supplemented such bounties with their own monetary awards. Lilly, of course, wasn’t the only hunter to exploit such opportunities to cash in on wildlife. In fact, around the same time frame two of this writer’s great-uncles were credited with having almost single-handedly cleared out the wolves and coyotes from Monona and Woodbury counties in far western Iowa.

The money Lilly earned by turning in skulls and hides supplemented the fixed salary the government paid him for his services. During his time as a hunter in the federal service he killed 55 mountain lions and a dozen bears—at least those were the ones he reported to his supervisors. He no doubt killed others for the privately offered rewards from Western ranchers. Some sources estimate Lilly killed as many as 1,000 mountain lions over his lifetime.

While the hunt itself was the driving passion and purpose of Lilly’s chosen career, the physical challenges he encountered and overcame were also an important part of his pathos. He seemed to relish reducing himself almost to the level of the animals he pursued. Lilly never carried a tent or sleeping bag, preferring to sleep in the open beneath little more than a length of canvas and a blanket. When the mercury dropped, he would employ various tried-and-true mountain man methods to build a fire, often siting them beside large rocks to better reflect the heat and keep him warm. On some occasions he would build a fire, let it burn down and then scoop out a sleeping berth where the coals had rested. On especially cold nights he would make his bed between two fires. He is not known to have sought treatment for or complained of damage from exposure or frostbite.

Lilly is known to have carried two lever-action rifles—a Winchester .30-30 for hunting mountain lions and smaller game, and a .33 Winchester for downing bears. True to form, the old hunter carried his shells in a tobacco sack. On his back he bore a large pack containing flour and other provisions, a knife, an ax and his bedding. He relied on his hunting skills to supply him with meat. Like the mountain men of old, Lilly savored “panther steak” and bear meat.

Lilly was also famed for his pack of devoted hunting hounds, which he trained to track and corner bears and mountain lions. Needless to say, he wouldn’t win the approval of present-day dog lovers. The hunter wouldn’t tolerate a hound that failed to demonstrate the killer instinct with which he himself was endowed. If one failed to meet his standards, Lilly would bring the offender before the other members of the pack, explain the dog’s failings and then kill the errant hound with a gunshot or club.

On the other hand, he was extremely loyal to the dogs that met his high standards. If he couldn’t feed his hounds, he would refrain from eating, and he always fed them from the kills he made with their help. The dogs would often tree lions and corner bears before Lilly delivered the coup de grace with rifle or knife. If they got far ahead of Lilly, they would surround their quarry and then work in relays to get nourishment without leaving the bear or mountain lion unguarded. Lilly took note of those that performed especially well, as did other hunters, who clamored for the pick of the litter of Lilly’s best hounds. He usually struck a hard bargain. Once when offered $300 for a hound descended from a particularly excellent tracker, Lilly would accept no less than $1,000.

Hunting aside, Lilly believed everyone should spend regular time in the great outdoors. “Every man and woman ought to get out and be alone with the elements every day, even if only for five minutes,” he said. “I can’t think at all except when I am out.”

As Lilly advanced in years, the tremendous physical exertions his hunts required began to tell on his previously iron constitution. Though he’d seldom been sick in his youth, in his later years he suffered pneumonia and stomach troubles, the latter brought on, warned a doctor, by overreliance on a mostly meat diet. Lilly’s mental acuity also went into decline. Among other signs, he would while away his time drawing cartoonlike pictures of bears and other game and then clumsily attempt to paint the pictures with watercolors. A rancher friend finally managed to persuade Lilly to room with him, but it soon became apparent the waning hunter needed full-time care. Lilly’s daughters were still living, as was a sister, but they couldn’t or wouldn’t take him in. Instead, he was sent to a county farm for indigent residents. Thus penned up, Lilly deteriorated rapidly, eventually hallucinating about hunting mountain lions and bears while wasting away in bed. He died of natural causes just shy of his 80th birthday on Dec. 17, 1936, near Silver City, N.M., and is buried in that city’s Memory Lane Cemetery. In many ways Lilly was the last of that intrepid breed of American frontiersmen who helped tame the West, though he’d remained wild as long as he could. Such independence was an enduring part of his legacy.

For further reading on the topic author Aaron Robert Woodard recommends Ben Lilly’s Tales of Bear, Lions and Hounds, edited by Neil B. Carmony, and The Ben Lilly Legend, by J. Frank Dobie.