On April 12, 1782, a force of Loyalist irregulars took Joshua Huddy, a Patriot militiaman, from custody aboard a British warship, rowed him to a desolate New Jersey beach and lynched him. Pinned to his body was a note: “We the Reffugee’s [ Grief Long beheld the cruel Murders of our Brethren…have made use of Capt. Huddy sic] having with as the first Object…to Hang Man for Man.”

The note ended, “Up Goes Huddy for Philip White”—a murderous equation conceived by William Franklin, renegade son of Benjamin Franklin.

Huddy belonged to the Association for Retaliation, a group of Patriot vigilantes who fought not British regulars but American Loyalists— labeled “Tories” by the Patriots. White was a self-proclaimed Loyalist Refugee in a paramilitary force led by Franklin. A ruthless guerrilla civil war—inspired more by vengeance than by ideology—was raging as the Revolutionary War neared its finish. On the very day Huddy was hanged by order of William Franklin, Ben Franklin was in Paris holding preliminary negotiations with a British official to end the war. The lynching of Huddy—a sad though relatively minor act—was to have international repercussions and threaten the peace talks.

By April 1782, six months after the British surrender at Yorktown, there was little military action between American and British forces north of Virginia. But guerrilla raids and skirmishes still bloodied what combatants called the “neutral ground,” a swath of northeastern New Jersey that lay between the British army stronghold in New York City and the Continental Army in the Hudson Highlands. Neither force fought to take the neutral ground. The fighting was primarily between foes like Huddy and White.

Huddy had not killed White. White was a Tory prisoner slain weeks earlier under suspicious circumstances by his Patriot captors. But Huddy had boasted of lynching another Tory, and for Franklin that was enough of a crime for him to order Huddy hanged. Joshua “Jack” Huddy had fought Tories on land and at sea. In August 1780 he was commissioned captain of Black Snake, a privateer gunboat that preyed on ships supplying the British troops in New York. A month later while he was ashore, the Black Brigade, a band of Tories led by a former slave known as Colonel Tye, trapped him in his home, torched it and captured him. Huddy escaped his captors that time. In 1782 he took command of the blockhouse at Toms River, a Patriot stronghold built to protect the local salt works.

On March 24, 1782, Tory raiders attacked the blockhouse. After seven defenders fell dead or mortally wounded, Huddy surrendered. The raiders then burned down the blockhouse, the salt works and the entire village. Their captors took Huddy and 16 other prisoners—four of them wounded—to British army prisons in New York.

William Franklin had negotiated an extraordinary agreement with General Sir Henry Clinton, commander of British forces in North America. Clinton gave the Board of Associated Loyalists—Franklin’s innocuously named guerrilla force —the right to hold prisoners rather than hand them over to the British.

Franklin ordered Huddy placed in the custody of Captain Richard Lippincott of a Tory regiment under Franklin’s control. Lippincott took Huddy from the prison to a British warship off Sandy Hook. A few days later Lippincott and a party of Associators, as Franklin’s guerrillas were called, returned to the warship and ordered a British naval officer to hand over Huddy. Franklin’s instructions to Lippincott were supposed to be secret, but the British officer later said he knew Lippincott was taking Huddy off to be hanged, for he saw a paper that contained the words “Up Goes Huddy.”

Lippincott and his men put Huddy in their boat and rowed to a bleak stretch of shore near Sandy Hook. The Tory captain walked his Patriot prisoner to a makeshift gallows, put a noose around his neck, pointed to a barrel under the gallows, gave him a piece of foolscap and advised him to write his will. Using the barrelhead as a desk, Huddy scrawled his will on the foolscap, adding a note on the back that read, “The will of Captain Joshua Huddy, made and executed the same day the Refugees murdered him, April 12th, 1782.” He then shook hands with Lippincott and climbed atop the barrel. A black Tory—likely an ex-slave given freedom for going over to the British—kicked the barrel from beneath Huddy’s feet. A few minutes later someone attached the “Up Goes Huddy” note, and Lippincott led his men away.

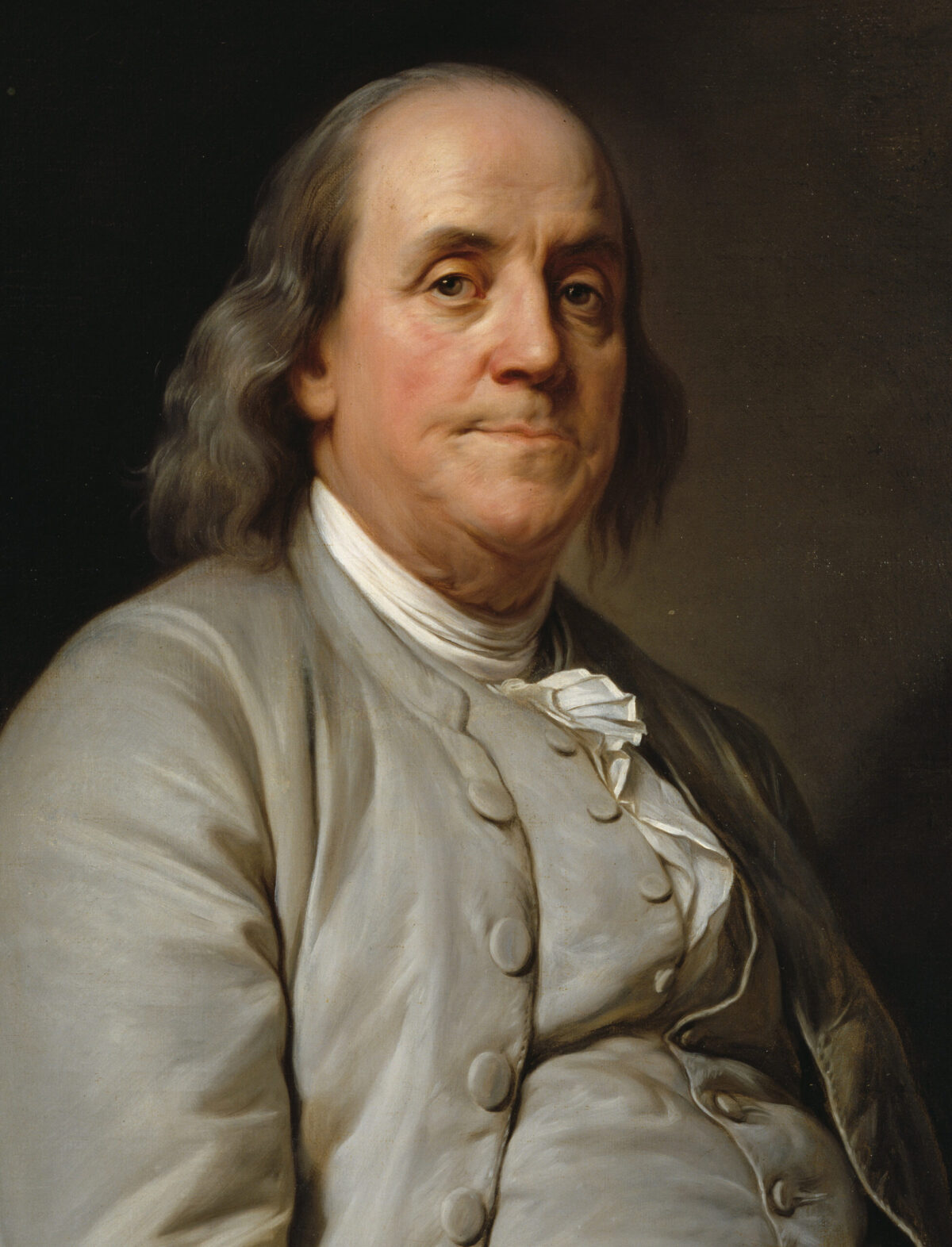

William Franklin’s odyssey from pampered son to merciless Tory began in Philadelphia, Pa., where he was born in either 1730 or 1731 to an unidentified “Mother not in good Circumstances.” The acknowledged father was Benjamin Franklin. He and his common-law wife, Deborah Read Franklin, raised the boy, whom his father called Billy. The elder Franklin doted on his son, taking him on various overseas trips, supervising his education and arranging for him to become a teenage officer in the Pennsylvania Militia. Ben said William grew so “fond of military Life” that his father wondered if he would ever return to civilian life. But he did, choosing the law and becoming, in the words of a friend of his father, a young man of “good sense and Gentlemanly Behaviour.” He was present during his father’s famed kite experiment with electricity.

William accompanied Benjamin to London in 1757, aiding him in his work as a lobbyist for the Pennsylvania Assembly. Sometime around 1759 William fathered an illegitimate son, William Temple Franklin. The boy’s mother, like his grandmother, was never identified, but his middle name suggests he was conceived while his father was studying at London’s Middle Temple court of law. Temple, as Ben Franklin always called him, was placed in a foster home, his upkeep and education paid for by his grandfather.

William, handsome and charming, rose high enough in British society to join his father at the 1761 coronation of George III. A year later Ben Franklin sailed home, leaving behind his son and grandson. William was busy advancing his career and wooing wealthy heiress Elizabeth Downes. Four days after their September 1762 wedding, King George made a surprising announcement: He tapped William Franklin as royal governor of New Jersey. After a stormy winter passage across the Atlantic, William and Elizabeth arrived in Governor Franklin’s colony in February 1763.

Owing to land disputes dating back to the 1670s, by the time William Franklin assumed his new post, New Jersey was divided into two provinces: East Jersey, whose capital was Perth Amboy, a seaport across from Staten Island; and West Jersey, whose capital was Burlington, near Philadelphia. The colonial legislature met in Perth Amboy, but the new governor chose to live in Burlington. For a time William, employing the social and political skills he learned from his father, managed to span the divide.

“All is Peace and Quietness, & likely to remain so,” Franklin reported in 1765 to William Legge, Lord Dartmouth, first lord of trade and later secretary of state for the American colonies. But his prediction did not come true. That same year the Sons of Liberty led numerous New Jersey protests against the Stamp Act. Franklin eased the crisis by ordering the hated stamps be kept aboard the ship delivering them from London, and he had the political wisdom to join in the celebration when the Stamp Act was repealed.

But when the tea tax uproar swept the colonies in 1770 and inspired a boycott, he showed his opposition by hold ing tea gatherings in the governor’s house. At one of the teas 9-year-old Susan Boudinot became famous for accepting a cup of tea, curtsying—and then emptying the cup out a window to show her support of the boycott. Her act symbolized the revolutionary fervor Franklin could neither escape nor ultimately control.

In 1774, when the First Continental Congress assembled in nearby Philadelphia, Franklin moved New Jersey’s seat of government from Burlington to Perth Amboy. He took up residence in the palatial Proprietary House, named after the Board of Proprietors, rich and influential landowners who became his most important supporters. The move distanced William from Philadelphia’s rumbles for independence, but Perth Amboy had its own homegrown rebels.

In January 1775 Franklin told Lord Dartmouth there were “no more than one or two among the Principal Officers of Government to whom I can now speak confidentially on public Affairs.” Three months later, after news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord reached New Jersey, he still clung to the hope that reason would prevail over revolution.

Then came the news that his father, accompanied by Temple, was in Philadelphia. The elder Franklin, who had returned to London in 1764 as a lobbyist, sailed home just in time to become the senior statesman of the American Revolution. As William entered Philadelphia to meet his father, he saw a city whose men were girding for war against the king. Rebel militiamen seemed to be everywhere, their “Uniforms and Regimentals as thick as Bees.” And, he realized, he and his father were drifting into their own conflict.

Joseph Galloway, Ben Franklin’s longtime Philadelphia friend, had just resigned from the Continental Congress after it rejected his proposal to create a colonial parliament but keep the colonies under royal rule. Ben was now as far apart from his friend as he was from his son. Yet Galloway, who had been William Franklin’s first tutor in the study of law, believed he could bring father and son together. He arranged for them to meet at Trevose Manor, Galloway’s sumptuous home some 20 miles north of Philadelphia.

The meeting did little more than dramatize the rift between Benjamin and William, who by then was a royal governor without an official legislature. New Jersey lawmaking was in the hands of a rebel Provincial Congress. Happily, however, there was another reunion: William met

Temple for the first time and invited him to New Jersey for the summer. Temple returned in the fall to his grandfather and schooling in Philadelphia. Temple and his father began corresponding with each other. Soon, though, William Franklin’s letter writing would abruptly cease.

Franklin’s attorney general was Cortlandt Skinner, a member of one of the state’s wealthiest families. Early in 1776, after learning the New Jersey Provincial Congress was about to order his arrest, Skinner fled to a Royal Navy warship in New York Harbor. Unlike other royal governors who made the same choice, Franklin remained defiantly in his governor’s mansion.

When the Provincial Congress declared him “an enemy to the liberties of this country,” Franklin protested using arguments both legal and vituperative. But the Continental Congress confirmed an order for his arrest and put Franklin in the custody of Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull, who had sided with the Patriots. Franklin’s first day of captivity happened to be America’s first Fourth of July.

Franklin partisans claimed he was placed in a notorious underground prison in Simsbury, Conn., whose cells were carved into the shafts of a former copper mine. Many Tories were jailed there, including some personally sent by General George Washington, but Franklin was not one of them. He was placed under house arrest and treated well.

Elizabeth Franklin remained at Proprietary House, a virtual prisoner, cut off from any correspondence with William. Her only comfort was Temple, allowed by Benjamin to spend the summer with his stepmother. In September, instead of returning to Philadelphia and school, Temple asked permission to visit his father in Connecticut. Benjamin refused the meeting, fearing William would turn Temple into a Tory. Around that time Congress called on the elder Franklin to negotiate an alliance with France, and when Ben sailed for Paris, he took his teenage grandson with him as his private secretary.

Meanwhile, William broke the rules of his parole, making clandestine contact with local Tories in Connecticut and others in New Jersey and New York. Congress punished him by confining him to a cell in Litchfield he later described as “a most noisome filthy Room.” There he received news his wife had fled to New York and died of what he later insisted was a broken heart. Plunged into depression and hoping his own life would soon end, Franklin was mercifully transferred to a private house. He remained there until October 1778, when he was exchanged for a ranking Patriot civilian captured during a battle a year before. Franklin headed straight for New York City and offered his services to General Clinton, who a few months before had assumed command of British forces in North America.

From the outset of the conflict New York, Britain’s American citadel, had drawn thousands of Tories, who called themselves “Refugees” to advertise their woeful status. Disorganized and despairing, they became William Franklin’s new constituency. Within weeks of his arrival in the city he had established the Refugee Club, which met in a tavern and plotted a new era for the embittered Loyalists.

The first public notice of Franklin’s organization came in a Dec. 30, 1780, newspaper article announcing the Associated Loyalists had been established “for embodying and employing such of his Majesty’s faithful subjects in North America, as may be willing to associate under their direction, for the purpose of annoying the sea-coasts of the revolted Provinces and distressing their trade, either in cooperation with his Majesty’s land and sea forces, or by making diversions in their favor, when they are carrying on operations in other parts.”

The 10-man board of directors, headed by Franklin and approved by Clinton, included Josiah Martin, the former royal governor of North Carolina, and George Leonard, a former Tory volunteer during the Battle of Lexington. In a short time more than 400 Loyalists became Associators. Franklin had regained his status as a Loyalist leader, though Clinton viewed him as a reckless agitator at a time when the war was winding down. Then came the outpouring of American outrage at the hanging of Huddy by a Franklin minion.

Even the Presbyterian minister who preached at Huddy’s funeral demanded retribution. George Washington, who called the hanging an “instance of Barbarity,” wrote to Clinton, warning that a British prisoner would be executed if Clinton did not turn over Lippincott. Clinton stalled by ordering that Lippincott be court-martialed for murder. Washington responded by directing that a British officer of similar rank to Huddy be selected by lot from prisoners of war and sent to the Continental Army encampment in Chatham, N.J.

Thirteen captive British officers in Pennsylvania were selected to draw a piece of paper from a hat. Twelve papers were blank. Captain Charles Asgill of the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards drew the paper with “unfortunate” written on it. He was the 20-year-old son of Sir Charles Asgill, a former lord mayor of London. Not only was Asgill from a prominent family and a famed regiment, but also, as a prisoner from the siege of Yorktown, he had a special protected status under an article of the surrender agreement.

Court-martial testimony from Lippincott and others revealed that Franklin had secretly ordered the hanging. In a scene sketched from the testimony, Lippincott appears before Franklin and members of the associated board before removing Huddy from the warship. Lippincott takes a paper from his pocket and shows it to Franklin, saying, “This is the paper we mean to take down with us.” Another official, peering over Franklin’s shoulder, interjects: “We have nothing to do with that paper. Captain Lippincott, keep your papers to yourself.” That paper, Lippincott testified, was “the very Label that was to be placed upon Huddy’s Breast.”

While the court-martial proceeded, General Sir Guy Carleton replaced Clinton as commander of British forces in North America, and Clinton sailed for home. Condemning “unauthorized acts of violence,” Carleton disbanded Franklin’s Board of Associated Loyalists, but he could do nothing about the court-martial.

Franklin was secretly readying to sail for London when the court announced its verdict: Lippincott, it concluded, convinced “it was his duty to obey the orders of the Board of Directors of Associated Loyalists,” had not committed murder. The court therefore acquitted him.

The verdict stunned Washington. He knew he had to make good on his threat of retaliation, which, he wrote, “has distressed me exceedingly.” Then came an unexpected reprieve for both Asgill and Washington. Asgill’s mother had written a pleading letter to Charles Gravier, the count of Vergennes and French foreign minister, asking him to intercede. Vergennes sent his own plea to Washington, along with the mother’s letter. Washington, touched by the display of maternal love and eager to please the French, submitted the appeal to Congress, which in turn compelled Washington to free Asgill.

Due to the long time it took for letters to travel, Asgill was not released until November 1782. By then William Franklin had fled to exile in London, and in Paris a peace commission had negotiated a preliminary treaty. One of the commission members was Ben Franklin; Temple Franklin served as its secretary.

Benjamin Franklin wrote a codicil to his will, disinheriting William except for an ironic bequest: a worthless piece of land in Nova Scotia, the destination of several thousand Tories who left the United States after the revolution. By the time Ben left France in 1785, he was a great-grandfather. Temple had just recorded the birth of his son with a diary note: “B a B of a B,” leaving readers to assume he meant “born a bastard of a bastard.”

William Franklin spent the rest of his life vainly seeking a rich reward for his service as a militant Loyalist and died in London in 1813. Lippincott joined the Tory exodus to Canada and was awarded 3,000 acres of for his military service. He settled in York (now Toronto), received half-pay for 43 years and died in 1826 at the age of 81. A street in Toronto bears his name.

Thomas B. Allen is the author of Tories: Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War. For further reading he recommends William Franklin: Son of a Patriot, Servant of a King, by Sheila L. Skemp;A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France and the Birth of America, by Stacy Schiff; and the website http://co.monmouth .nj.us/page.aspx?Id=1800, which contains “documents created during, or immediately after, the life of Joshua Huddy.”

Originally published in the January 2014 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.