In early 1949, Riley B. King, 23, was living and working as a tractor driver on a plantation outside Indianola, in the Mississippi Delta, where he mostly had grown up. A sharecropper’s son determined to pursue a career in music, Riley busked playing the blues on the street and had had a gospel group and, as often as he could, and despite his stutter, chatted up working musicians. At Jones’ Night Spot in Indianola, he had buttonholed Sonny Boy Williamson, famed regionally for his lunchtime radio show, broadcast out of West Memphis, Arkansas. Now Riley was heading to that town, hoping to break into the music business.

Riley bid farewell to planter Johnson Barrett. “I’ll send for you, soon as I get settled,” he told his wife, Martha. Guitar in hand, he hitched a ride in a Lewis Grocery truck, helping the driver make deliveries in exchange for passage to West Memphis, across the Mississippi from Memphis, Tennessee. Against the March chill he wore the field jacket he’d gotten during a brief wartime stint in the U.S. Army.

His destination was 231 East Broadway, the studios of KWEM, which had launched in 1947 on a pay-to-play system. Local performers could book a time slot by ponying up $15 or $20 or find a sponsor to cover the cost. One of the station’s first stars had been Chester Burnett, a giant of a man from the Mississippi Hill Country who performed as Howlin’ Wolf.

Wolf’s voice, a bone-rattling bass baritone growl, froze listeners in their seats.

KWEM’s other star was Sonny Boy Williamson. Born Alex Ford around 1912 on a Mississippi plantation, he mastered the harmonica and by the 1930s was traveling around Mississippi and Arkansas and performing with many singers and guitarists, including Robert Johnson.

In 1941, Ford landed on the air at KFFA in Helena, Arkansas, playing music and touting baking products on a show, “King Biscuit Time,” named for sponsor King Biscuit Flour. Sponsors supposedly rechristened Alex Ford “Sonny Boy Williamson” to exploit the brand of a Chicago musician already recording under that name.

In 1948, Sonny Boy moved to West Memphis and KWEM, arriving shortly after Wolf, a friend he had taught to play harmonica. Sonny Boy’s sponsor was Hadacol, a patent medicine marketed as a vitamin supplement for the entire family. In truth, the “Wonderful Hadacol Feeling” was actually inebriation; the stuff was 12 percent alcohol (American Schemers, April 2018).

For years, Riley and the other hands at Barrett’s plantation had been coming in from the fields at lunchtime to relax listening to Sonny Boy. And there had been that encounter at Jones’ Night Spot. “I felt I knew him,” he recalled. Still, Riley could not explain how he summoned the nerve that Wednesday to walk into KWEM, clutching his guitar and asking for Sonny Boy. He found Williamson in the studio, finishing a number with guitarist Robert Lockwood Jr. and pianist Willie Love. When he had finished playing, Sonny Boy gave his visitor a hard look.

“What do you want?”

Riley took a deep breath and tried his best to remember those warm memories he treasured of Sonny Boy on the radio.

“I…I…I…I wanna sing a song on your program,” Riley B. King stammered.

“You do, huh?”

“Yes, sir.”

Sonny Boy and his band members now remembered the night a few years back when a boy with a stutter had peppered them with questions in Indianola.

“Go ahead,” Sonny Boy said. “Lemme hear you.”

Riley swung his guitar around and lit into “Blues at Sunrise,” which had been a hit for Ivory Joe Hunter. “I sang with all the soul I could muster,” he recalled. “My guitar hit the right notes and I sang in tune.” He waited for Sonny Boy’s verdict.

“What do you call yourself, son?” the radio host asked with a flicker of warmth.

“Riley B. King.”

“All right, Riley B. King,” Sonny Boy said. “You can sing your song at the end of my program. Just be sure you sing as good as you did just now.”

Riley stood by until Sonny Boy gave him a nod. At the microphone he played and sang as well as he ever had. When he was done Sonny Boy took back the mic.

“The boy ain’t bad, but you tell me what you think,” Williamson told his listeners. “Call in if you like him.”

As Sonny Boy was wrapping up, Riley waited. A White man came into the studio and announced that many listeners were calling in to praise Riley’s performance. Then he whispered in Sonny Boy’s ear.

“Shit,” Sonny Boy Williamson said. “I done messed up.”

Riley started to panic, thinking he was somehow at fault.

“Lookee here, Riley B. Seems like I double-booked myself,” Sonny Boy explained. “I’m working down ‘round Clarksdale tonight, but I also got me another date at that Sixteenth Street Grill here in West Memphis. You wanna play the Grill for me?”

“Yes, sir,” Riley replied in an instant. He was “thrilled beyond reason,” he recalled. “Giddy and silly and screaming hallelujah inside.” In the space of an hour, he had debuted as a radio bluesman and earned his first paying solo gig.

Sonny Boy picked up the telephone and placed a call. “Did you hear the boy who just sang?. . .How did you like him?. . .Well, I’m gonna let him work for you tonight.” He hung up.

“I want you to go down and play for Miss Annie at the Sixteenth Street Grill,” Sonny Boy said, menace in his voice. “And you better play.”

“Yes, sir,” Riley replied.

The club, a block off Broadway in West Memphis, was variously known as the Square Deal Café, the Sixteenth Street Grill, and Miss Annie’s Place, after owner Annie Jordan. Miss Annie showed Riley around. “The joint was just a couple of rooms,” he recalled. “One up front for music and sandwiches, one in the back for gambling.”

“I got me a jukebox in here,” Annie told Riley. “But I turn it off ‘cause the ladies like to dance to a live man.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

A live man. The words danced in the young musician’s head. And sure enough, as showtime approached, a procession of ladies filed into the café, some with escorts, some without. The men retreated to the gambling parlor, leaving their dates up front to dine and dance.

Having no better clothes, Riley took the stage wearing his field jacket. The ladies didn’t seem to mind. “For the first time I played for dancers, played for these ladies who moved so loose and limber that I played better than I’d ever played before,” he recalled. “Might have messed up my musical measures or screwed up a lyric or two, but, baby, the beat was there.”

Riley filled Miss Annie’s Place with the blues, his only accompaniment his Gibson guitar running through a tiny amplifier as he sang through a small public address system. He held down the beat, and the dance floor filled with hot, heaving bodies.

“I want to hire you,” Miss Annie said afterwards. “But you can’t help me get business unless you’re on the radio, like Sonny Boy is. If you can get on the radio, I’ll pay you $12 a night and give you room and board.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Riley replied. “I will get on the radio.”

The club owner offered to put him up. “That night I couldn’t sleep for the pictures running through my head,” he recalled. He imagined women in various states of undress, “bending over and stretching, grinding and grinning and showing me stuff I ain’t ever seen before.”

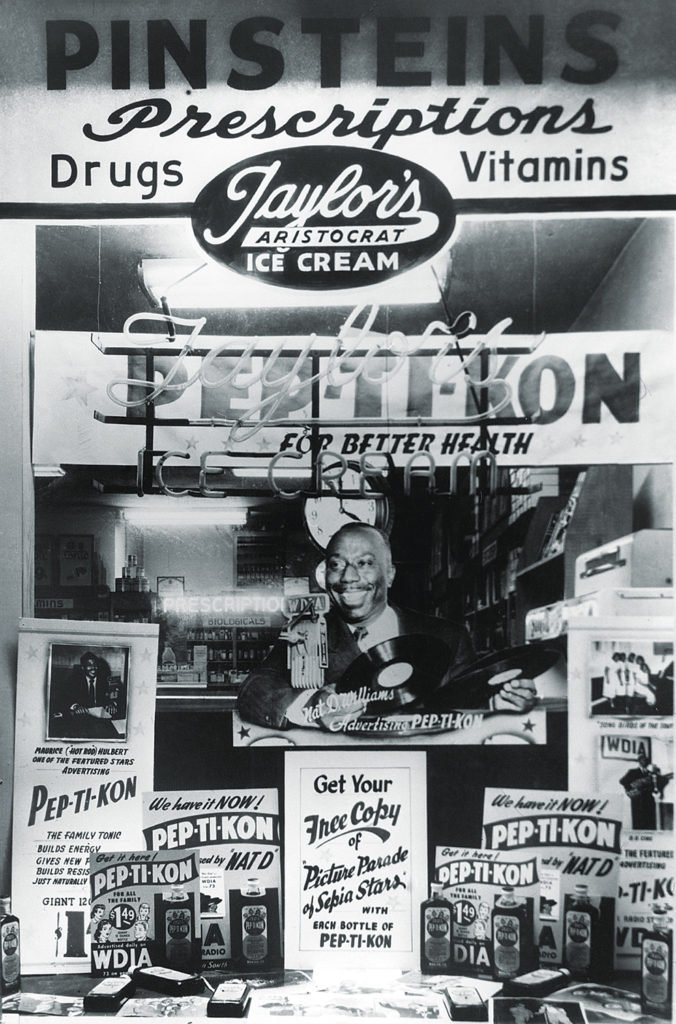

The next day, Miss Annie told Riley about WDIA hiring Black deejays like local celebrity Nat D. Williams. On previous forays to Memphis, Riley, with his cousin Bukka White, had played Nat D.’s amateur nights at the Palace. Guitar in hand, Riley caught a bus for Memphis to find WDIA.

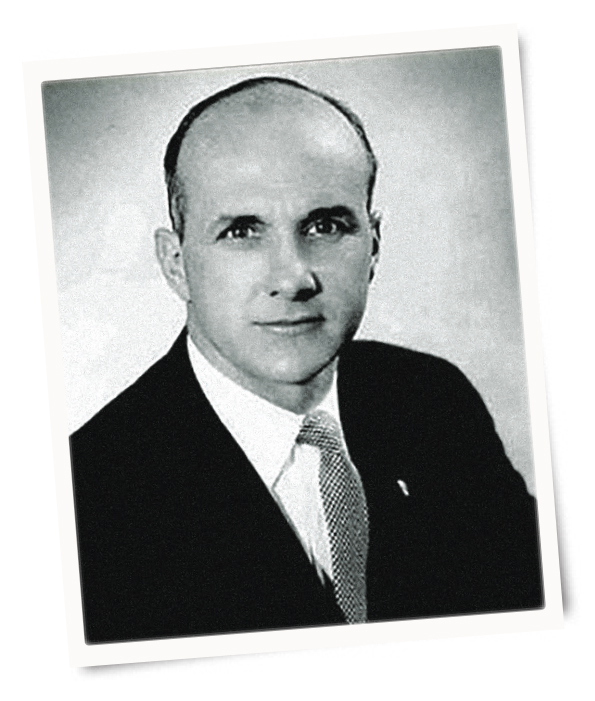

WDIA, 1070 AM, Had Commenced operations on Union Avenue in the summer of 1947. The founders were White men. John Pepper, the businessman, was a scion of an affluent Memphis family; WDIA was named for his daughter Diane. Bert Ferguson, the station manager, was short on cash but long on experience. Eight years earlier, Pepper had brought Ferguson in to run WJPR-AM in Greenville, Mississippi. The two were looking for a niche in the Memphis market, dominated by five stations with ties to national networks and celebrity disk jockeys.

WDIA started out playing country-and-western. When that format failed to attract listeners, the owners tried pop and even classical music. Now they were back to country, airing shows like “Cracker Barrel” and “Hillbilly Party.” Nothing was working. Christine Cooper, Ferguson’s programming director, searched in vain for the right format. Chris Cooper, 23, was a striking woman, taciturn and serious, with soulful brown eyes and a sharp mind. Ferguson had lured her from an ad agency to become one of the first women in Memphis radio.

In spring 1948, Cooper was wondering if she had made the right choice. WDIA was hovering near bankruptcy, and the owners seemed desperate. Cooper and Ferguson and two other station employees, to save on hotel bills, had left an industry convention in Nashville early and were driving the 200 miles to Memphis.

Ferguson was at the wheel, with Cooper riding shotgun. As they were rolling past moonlit farmhouses on two-lane blacktop roads, Ferguson leaned toward his program director.

“What do you think about programming for Negro people?” he whispered.

Cooper considered. Their competition in Memphis had divvied up the region’s White audience. No mainstream station was programming for Blacks, a potential audience as large as the entire White market—“tens of thousands of people with names and faces who had served me at restaurants and ridden on the same bus,” she recalled. Blacks in and around Memphis had their own clubs, their own festivals, and even a newspaper—the Memphis World—but no radio station. Cooper told her boss she loved his idea.

“Would you object to working alongside Negro people at the station?” Ferguson asked, again speaking sotto voce.

No, Cooper replied, she would not.

After that furtive exchange Ferguson dropped the topic. Cooper thought he had lost his nerve or his focus. He was always coming up with new concepts, sometimes with Pepper. Lately the two had been pushing a tonic they had dreamed up to compete with Hadacol and had gotten so far as to organize a company to sell it. Ferguson had tried to get her to write the ads, but she refused. But Bert had not lost focus on taking WDIA Black. That October he told her he had decided “to go ahead with it.” Chris knew instantly what “it” was.

African American radio had begun in the 1920s with a visionary named Jack Cooper. Born in Memphis in 1888, Cooper made his name reporting for Black newspapers in Chicago, Illinois. In 1925, on WCAP in Washington, DC, a strong Black market, he launched a variety show. Cooper performed dialect skits; he joked later that he had been “the first four Negroes on radio.” Returning to Chicago, in 1929 he brought out “The All-Negro Hour” on WSBC, patterning this show on African American vaudeville line-ups.

Broadcasters favored live material so they could skirt hefty fees the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers charged stations to play and broadcast recorded music. The modern disc-jockey figure, a record-spinning on-air personality, arrived in 1932, when Jack Cooper invented that role. In a dispute over pay, a musician scheduled to play one of Cooper’s shows instead walked out of the studio. By one account, to rescue the moment the impresario “got a barrel and set some little record player on it and held a mike to it.” Thus, the first deejay.

By WDIA’s day, African American performers were popping up on the airwaves all over the South. Bert Ferguson had put Riley King’s gospel quartet on the air in Greenville.

But Black deejays remained rare, and no station in the United States had an all-Black format. That became Ferguson’s goal.

His first choice to spin discs at WDIA was Nathaniel D. Williams, a history teacher in the Memphis public school system who had built a sideline in multiple media.

Besides teaching, Williams, as “Nat D. Williams,” wrote a column for the World and hosted the weekly amateur night competition at the Palace Theatre, broadcast live by a WDIA rival. Williams’s compact frame and Coke-bottle glasses were familiar to all of Black Memphis.

Williams agreed to work at WDIA. His weekday shift would start after school. Now came the ticklish task of naming his show for promotional purposes without ruffling Jim Crow’s feathers. Even “Negro,” while nominally acceptable, was too blunt for the radio program listings in the Memphis Commercial Appeal, sending Cooper and Ferguson to a thesaurus. They considered “brown” and “sepia” before settling on “tan,” which sounded like a day at the beach. Nat D. Williams would be hosting “Tan Town Jamboree.”

Williams was to debut at 4 p.m. on Monday, October 25, 1948. He arrived at the station breathless, having raced across town from Booker T. Washington High. He took a seat at the microphone, collecting himself. At the top of the hour, his White announcer cued him. Williams sat in silence, mind a blank. Seconds ticked by. Williams, realizing the absurdity of his predicament, erupted into a long peal of laughter. Soon everyone in the studio was joining in, and “Tan Town Jamboree” was rolling. That big, cathartic laugh became Nat D.’s trademark.

Not everyone was laughing. Backlash to “Tan Town Jamboree” came swift and fierce.

“For the first three weeks, we were just plagued with calls—‘Get that n——off the air!’” Cooper recalled. “My boss got death threats.” Station personnel fielding complaints politely reminded callers that if they did not like what they were hearing they were free to turn the dial.

Complaints from White listeners died down. With the most famous Black man in Memphis on the air every afternoon, WDIA’s Black listenership exploded across Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi. Thanks to radio’s unifying power, the “Jamboree” became a virtual town hall for every Black community within 60 miles.

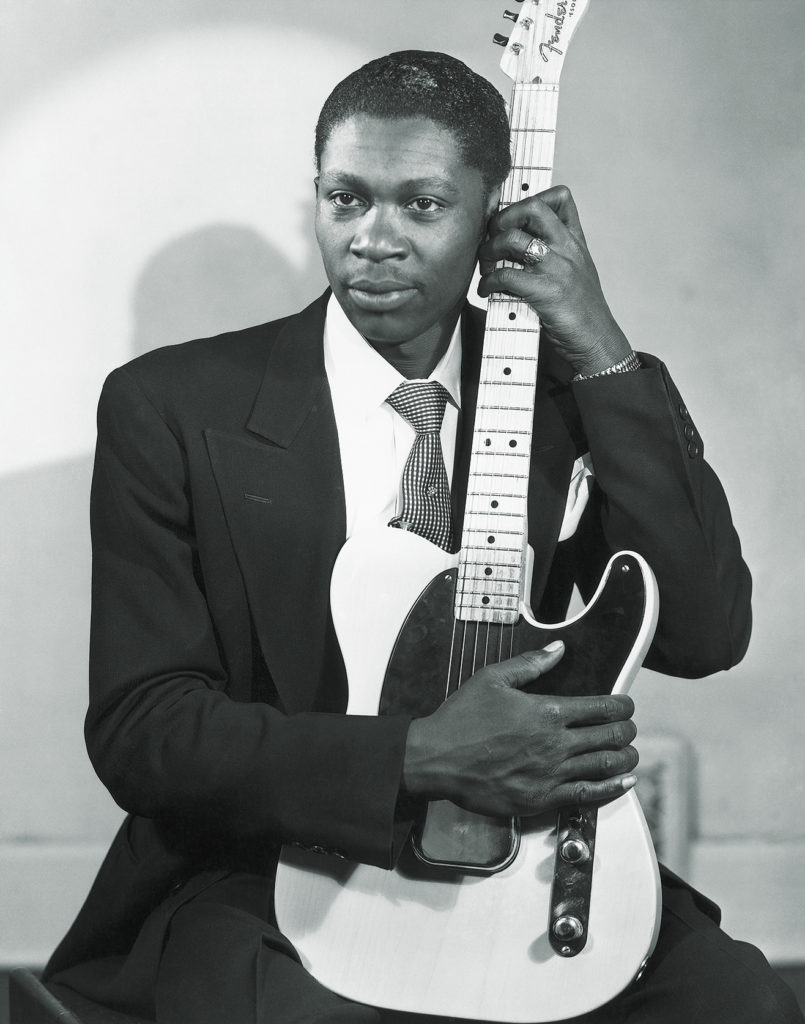

Riley’s last quarter GOT HIM as far as the bus station in downtown Memphis. It was three miles to WDIA. He cinched the cotton-sack strap he used to secure his fatigue jacket against the chill and rain. His guitar still lacked a case. Moving at a trot, he hugged the instrument, its f-holes against his chest to keep water out.

The station’s offices vaguely resembled a giant brick radio, with the art-deco call letters bolted across the building façade. Riley later described himself peering through a large plate-glass window and seeing “a black man with super-short hair and super-thick glasses”: Nat D. Williams, in the studio. A red light was on, meaning, Riley knew, that the deejay was on the air. When the red bulb dimmed and a green light went on, Riley tapped the glass. Williams beheld “a brown-skin fellow standing there with water dripping off his battered old hat, water oozing out of the soles of his shoes. Drenched all over with a worn and really battered old guitar under his arm. He stood there looking wistfully at me through that glass partition.”

Chris Cooper remembered the scene differently. Riley simply appeared at the front desk. “He went to the receptionist with his dripping-wet umbrella and his guitar held tight to his chest,” she recalled.

The receptionist called Bert Ferguson. “He came down from his office,” Cooper said. “And she said, ‘Somebody’s here who wants to record.’”

Much later Riley remembered Bert Ferguson as “a short Jewish man, not much hair, with a serious air about him.”

The manager regarded his visitor. A close-cut, ragged pompadour topped Riley’s smoothly symmetrical clean-shaven features, with wide-set eyebrows above mournful eyes. He was wiry, with powerful hands that spoke of farm work.

“We don’t make records,” Ferguson said. Still, he said, “We might be able to use you. If I put you on the radio, would you be too nervous to talk?”

“I might do a little st-st-st-stuttering,” Riley stuttered. “But no more than the average person. I think the average person will take to me.”

Ferguson asked about his background. Riley told about singing blues on the corner in Indianola and singing gospel on the radio. Ferguson remembered having met him that time in Greenville. Riley explained about singing for Sonny Boy on KWEM and his new gig playing at the Sixteenth Street Grill. WDIA production manager Don Kern joined them. Riley played for the radio men, perhaps the first time he had ever played the blues in front of an attentive White audience. Assuming correctly that his listeners knew little about the blues, he did “Caledonia,” Louis Jordan’s jumping number about a woman with “great big feet.” When Riley finished Kern said, “You’re all right.” He and Ferguson smiled.

“And mentioning Sonny Boy gives me an idea,” Ferguson said. “Sonny Boy’s made quite a splash advertising Hadacol. Well, we have a sponsor called ‘Pep-Ti-Kon.’ Good for whatever ails you. And we’re looking for someone who can sell it. I’m thinking that one way to sell it [would be] through a song. You ever written a jingle?”

“No sir,” Riley replied.

“Willing to try?”

Riley sat with his guitar for a few minutes, humming a melody, then, against a simple blues progression, sang, “Pep-Ti-Kon sure is good/And you can get it anywhere in your neighborhood…”

Ferguson beamed. He strode off and returned with Cooper. The program director saw a guitar dripping against a wall and a slender Black man, head bowed, also dripping, like some Delta apparition. Ferguson told the visitor to sing something. When the fellow stepped to the microphone, he seemed to transform. “He just straightened up,” Cooper recalled. “And he hit his guitar like he knew what he was doing.”

She was expecting to hear one of the minstrel songs she knew—“Old Black Joe,” or “Swanee River,” Stephen Foster chestnuts. Decades later, Cooper, who before that day had never heard Delta blues, could not remember what Riley did play but she was certain of her reaction to hearing him.

“It just tore me apart,” she said.

Riley recalled his choice of song as having been another Louis Jordan number, “Somebody Done Changed the Lock on My Door,” an exercise in wordplay along the lines of “Caledonia.” But the “key” and the “lock” were a double entendre, and Riley played the song for every bit of its carnal meaning, raw and sexual and coarse, voice burning with menace and lust, sodden guitar buzzing with an angry twang. The music and the lyrics made the young program director want to rip open the studio door and run into the street. She felt shaken, upset, unnerved. And then she thought that maybe this rough, sensual music was exactly what WDIA’s new listeners wanted. Riley finished singing.

“Let’s put him on the air,” Cooper gasped.

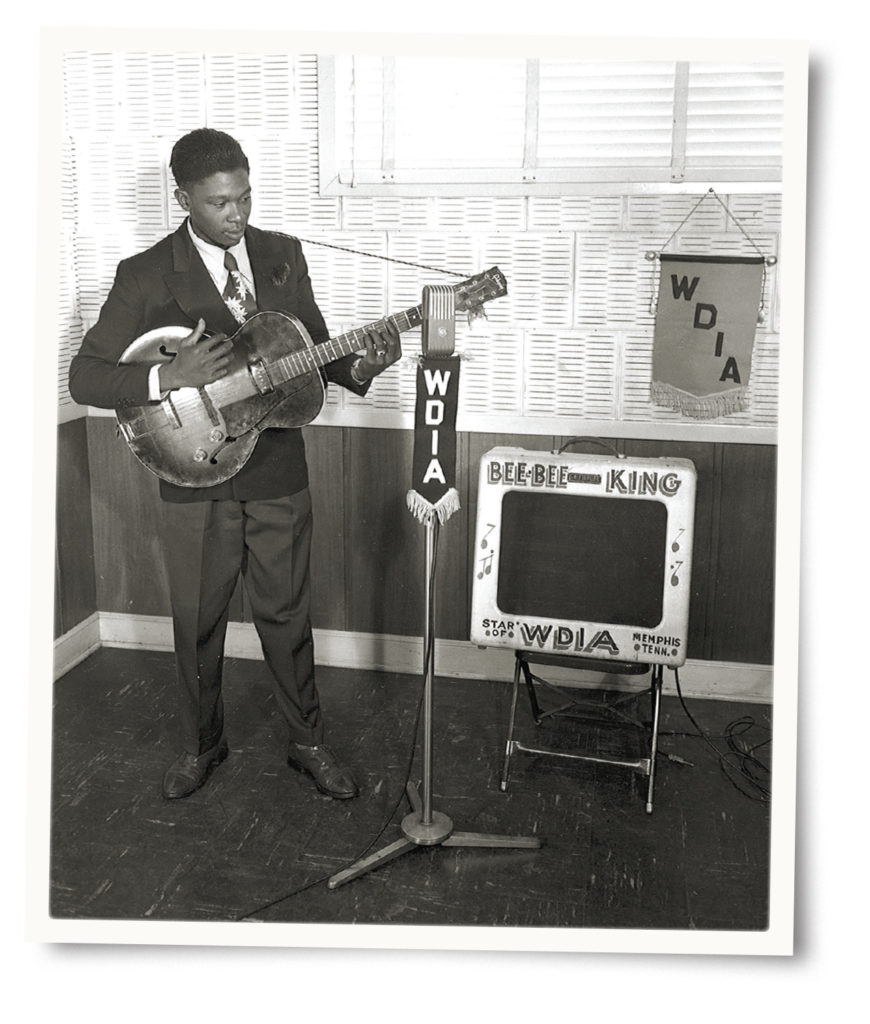

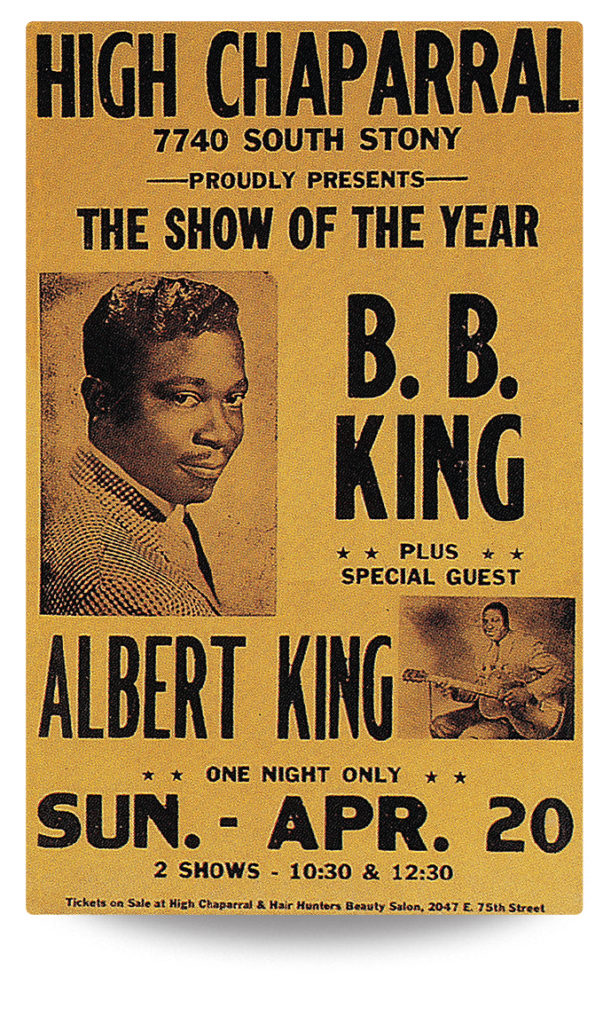

Boldness earned Riley B. King a regular 15-minute slot on WDIA following station mainstay Nat Williams. Per Bert Ferguson’s decree, the station billed him as “BB King.” Though not paying him—on the air, he could promote his shows at Miss Annie’s, which paid several times what he had been making at the wheel of a tractor—station management welcomed him into a familial workplace where everyone was “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” or “Miss” regardless of skin color. Riley sent for Martha and they moved into a boardinghouse in Memphis. By autumn 1949, WDIA’s programming had shifted to all-Black, and B.B. King had begun a long march to global musical stardom.